Skin

Authors: Ilka Tampke

Ilka Tampke was awarded a Glenfern Fellowship in 2012. Her short stories and articles

have been published in several anthologies. She lives in Woodend, Australia.

Skin

is her first novel.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Ilka Tampke 2015

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of

this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner

and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2015 by The Text Publishing Company

Cover and page design by Imogen Stubbs

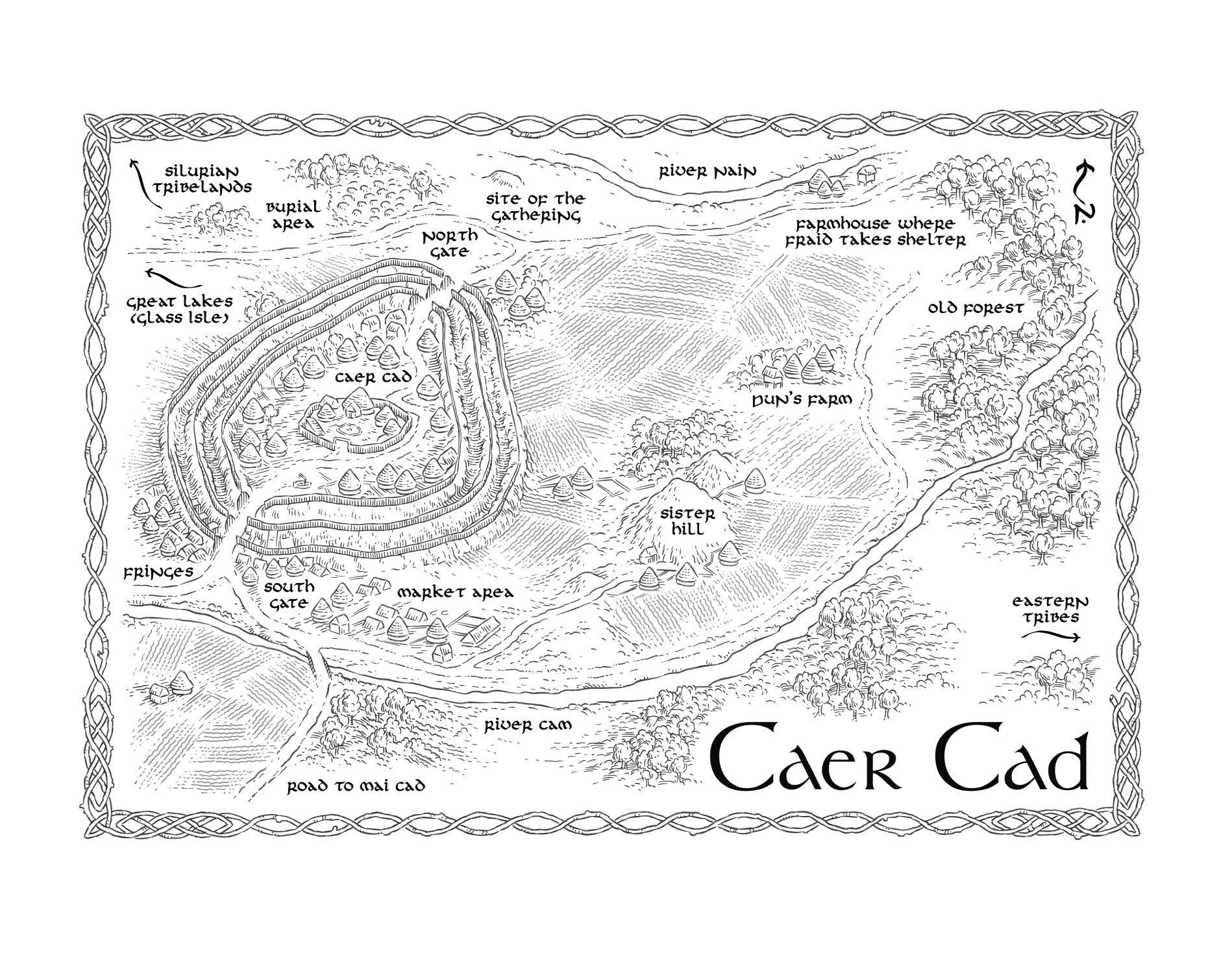

Map by Simon Barnard

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Creator:

Tampke, Ilka, author.

Title:

Skin / by Ilka Tampke.

ISBN:

9781922182333 (paperback)

9781925095319 (ebook)

Subjects:

Love stories.

Great BritainâFiction.

Dewey Number: A823.4

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia

Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

For Adam, Amaya and Toby

Contents

The world was born of a great flood. These waters were Truth and washed over everything.

Some saw the river as it came and were well minded enough to transform themselves

into salmon. By this means they survived. They were the wise ones.

SOUTHWEST

BRITAIN

,

AD

28

I

WAS

NOT

yet one day old when Cookmother found me on the doorstep of the Tribequeen's

kitchen. She was on her way to our herb garden after tasting her stewed pork and

finding it wanting in rosemary. I very nearly felt her leather sandal upon me before

she noticed my tiny, swaddled shape.

I knew the story well.

âMothers of earth!' She carried me inside, laid me on the table and peeled open my

wraps, powdery with frost.

I was a girl. Misshapen, no doubt, for why else would I have been left for the Tribequeen's

servants to care for? Cookmother ran her callused fingers across my wrinkled back,

my flailing limbs and swollen belly. My cord had been torn, its stump still raw and

crusted, and my eyes were sunken with thirst. But she found nothing else wrong. I

was

perfect. A poor mother then, or a mother in shame? But Cookmother could not recall

any women from the fringes who'd been due with child.

I squalled at the smell of her. I had not yet known a mother's touch nor the taste

of her milk.

Cookmother sat down on a stool and let her leine fall open so I could suckle greedily

from her well-veined breasts, still full to bursting for the second warrior's new

child.

And when she had to tear my mouth away to tend to the spitting cookpot, she laid

me down on a goatskin in front of the fire, where Badger, the old black-and-white

bitch, was resting from the mouths of her own hungry pups outside. And when I howledâtwo

hours on a stone step at midwinter had given me a coldness that needed touch and

I had not yet drunk my fillâCookmother placed me beside Badger's flaccid abdomen

and my little mouth easily found a nipple. Badger lifted her head and smelled me

curiously, too exhausted from seven successive litters to snout me away.

Over the months that followed I fed often in this way. Cookmother said I was half

reared on dog's milk. She wondered if this had some part in what became of me.

Perhaps because I was well formed, or because the season's harvest had put all in

good temper, I was kept in the kitchen as Cookmother's own. She had treated many

lost babes, then given them to the warrior families or, if they were too weak, to

the builders, for a child-soul in the foundations would bring great protection to

a new house.

But I lay in a tinderbox lined with lambskin while Cookmother ground the grain, dried

the meat and ran the Tribequeen's kitchen. She was busied all the sun's hours and

my cries were often silenced with a sharp word and a finger dipped in pig fat or

salted butter. But at the end of each day I was nuzzled to sleep in her own bedskins

and

the murmurs of her dreams were my nightsong.

Her temper was hotter than a peppercorn and my cheek often felt the sting of her

palm, but when I was two summers old and burned my wrists at the rim of the cookpot,

it was she who applied a fresh poultice while I writhed and screamed, and she who

held me through the night when the smarting was unbearable. And when the Tribequeen

called for girls of able wit to be sent for service to one of the eastern tribekings,

it was she who shut me into a wooden chest with a command to be silent, and told

the messenger I had taken to wandering the fringes and who knows what infections

I was picking up there.

Cookmother was plump and warm, like a fresh-filled sausage, although to look at she

was as ugly as a toad, with a toothless laugh and skin as pocked as porridge. Her

legs (when I burrowed beneath her skirts, hiding from a loud-voiced farmer or loosed

bull) were so gnarled that I wondered, in my earliest innocence, if she was half

kin to a tree. This was before I knew the workings of the body and learned these

dark, knotted roots to be pathways of blood.

The tribelands in which I grew were those of Durotriga in Southern Britain. Of the

many regions within it, ours was called Summer, a wetland country, named for its

abundant yield of barley, oats and wheat, where grass grew as lush as a deer pelt,

and teemed with rivers.

My township, perched on the plateaued crest of Cad Hill, was Caer Cad, one of the

largest hilltowns of Durotriga. The walled banks and deep ditches that encircled

it were beginning to crumble, for peace had sat upon this tribe for many seasons.

The only strangers breaching our gateways now were traders from the Eastlands, who

chuckled at our round earthen houses built all alike, their doorways aligned to the

midwinter sunrise. They called them anthills and thought us simple. But our journeymen

and -women did not seek to

display their knowledge through mighty buildings. Their

greatness lived elsewhere.

I was an inquisitive child with a watchful eye. What pleased me most was seeing life

at its arrowhead: Badger and the endless stream of pups that spewed from her swinging

belly, the ice crystals in the river at wintertime, the spill of young fish that

filled it in spring.

What frightened me was being alone.

There were five in our house. Of my three kitchen sisters, Bebin was my favourite,

steady and never shooing me away when I followed her to market or to the Tribequeen's

sleephouse. I was less fond of Cah, sharp and changeable as the west wind. Ianna

was our spinner, without wits for much else.