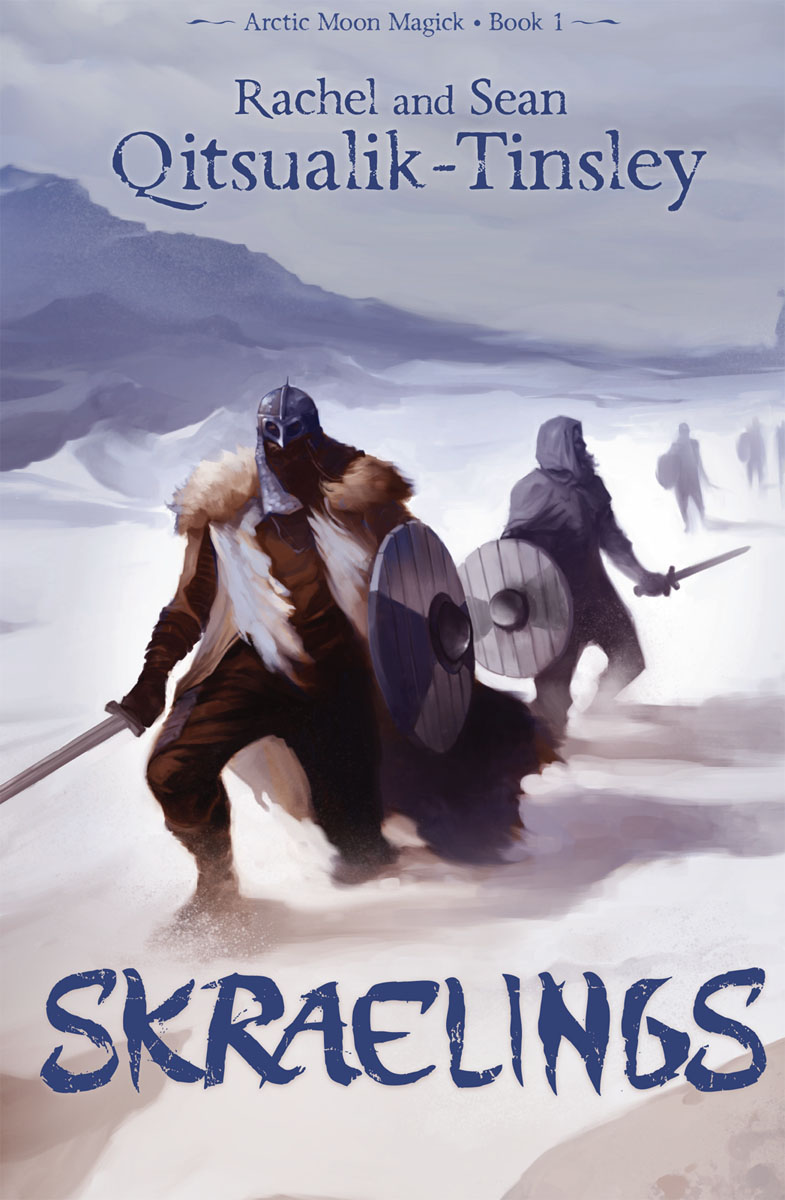

Skraelings: Clashes in the Old Arctic

Read Skraelings: Clashes in the Old Arctic Online

Authors: Rachel Qitsualik-Tinsley

Published by Inhabit Media Inc.

Inhabit Media Inc. (Iqaluit), P.O. Box 11125, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 1H0 (Toronto), 146A Orchard View Blvd., Toronto, Ontario, M4R 1C3

Design and layout copyright © 2014 Inhabit Media Inc.

Text copyright © 2014 by Rachel and Sean Qitsualik-Tinsley

Illustrations by Andrew Trabbold copyright © 2014 Inhabit Media Inc.

Editors: Neil Christopher and Louise Flaherty

Art director: Danny Christopher

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program.

We acknowledge the support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage Canada Book Fund program.

Printed in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Qitsualik-Tinsley, Rachel, 1953-, author

Skraelings : clashes in the old Arctic / Rachel and Sean

Qitsualik-Tinsley.

ISBN 978-1-927095-54-6 (pbk.)

1. Inuit--Juvenile fiction. I. Qitsualik-Tinsley, Sean, 1969-, author II. Title.

PS8633.I88S57 2013Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â jC813'.6Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C2013-908382-0

Unknown Places

Here's the story of a young man who, at the time of his tale, had no clue where his family might be living. If you had been there to ask, the best answer he might have given is:

“Somewhere behind me.”

Not that he was lost. No, it was simply that happiness means different things to different peopleâand it was his great joy to travel across strange lands. He went without human companionship. He had no idea where he was going. There were no enemies in his life. No friends (except maybe his sled dogs). Yet not one of these facts meant that he was lost.

Unknown places, even uncertainty about where he would next sleep or eat, rarely frightened the young hunter. You, however, whoever you are reading this, would have scared him. Not because you have two heads, or you're coloured green, or you come from another planet. No, it's exactly because you come from the same planet as him that you might have scared this person.

You see, you are from another

time.

On our

earth, the earth that you know, the world is choked with people. We can see them on TV. Sit with them on an airplane. Brush shoulders with them in busy halls or on the street. Unless you're very lucky, you don't know what quiet is. Real silence. Not the quiet you get when folks stop yammering. We're talking about the silence of standing alone in the wide Arcticâon the great Landâwhere only the wind or an odd raven whispers from time to time, and the loudest sound is your own breath.

That kind of quiet has a heaviness to it. A life of its own, you might say. And that is the sort of quiet our hunter was used to.

This is not to say that you couldn't have been friends with the young man, since he was very much a human being, like yourself. It is simply that, even if, by some magic, you could have spoken a common language with him, your ideas of the world would have been very different. To be honest, the easy part would have been explaining televisions and airplanes to him. Even busy halls and streets. But how would you have gotten across the simple idea of a country? Or a border? In our world, the earth is so crowded. There are so many rules. It's normal that everyone knows their citizenship. You can barely move without a passport. And you can't step on a clot of land that hasn't been measured and assessed for its value. It would be strange to hear of land that isn't owned. Every inch of dirt, in our time, belongs to somebody. In our world, people even talk about who should own the moon.

But the young hunter's land was not just dirt, you see. It was not land with a little “l”: something we can measure and pretend to own. His was the Land. And he called it

Nuna.

And like everything under the Sky, it had a life of its own.

Land as property would have made the young man and his relatives laugh. After all, the Nuna was a mystery. No one knew its entire shape or extent. Humanity did not set limits on the Land. The Land set limits on humanity. It was the Land, including the sea that bordered it, that made demands on how all life existed.

“No one can even control the Land,” Kannujaq might have told you, “so how can one own it?”

That was the young hunter's name, by the way: Kannujaq. He was named for a mysterious stuff that came from the Land. In his language,

kannujaq

described a funny, reddish material. It was rare, but known to a few of his people. You probably would have recognized it, called it “copper,” and tried to tell Kannujaq that it was a metalâbut that would have meant very little to him. You see, a tiny bit of copper was the only metal he had ever seen. You might have then tried to explain to this young hunter that he only thought copper was special because he lived in the Arctic, and so long ago.

But we almost forgot: you can't tell Kannujaq anything. It would be over a thousand years before we could write about Kannujaq, much less let you read about him. And no matter how hard Kannujaq dreamed, he could never have imagined people like us.

In Kannujaq's time and place, he was usually too busy to dream, anyway. The Land never let his mind wander for long, holding him in an eternal moment. To this day, it has that power, the ability to force the mind into a single point of attention. Visit it sometime. Find a place away from “progress.” Maybe you'll see why the Land was such a beloved mystery to Kannujaq and his folk. While you're on the Nuna, stand on a windswept ridge. Raise your arms, open to the grand Sky. And imagine how Kannujaq stood.

Kannujaq's eyes were closed, his nostrils pulling in the pure air, and the silence was such that he seemed to detect every stirring in his world. A raven muttered, and he opened his eyes to spot one on a nearby, lichen-encrusted boulder. Another wheeled in the sky above him. He smiled, knowing that the birds resented his presence, and his eyes panned over the rocky ridges that played out before him. The low slopes mixed shades of brown, a bit of purple, some bits of dark green from heather and willows that grew no higher than his knee. In the troughs between the slopes, the low valleys, there was barely enough snow for his dogsled. By now, he was soaked with sweat. Long tongues dangled from the mouths of his exhausted dogs.

Kannujaq's smile eventually faded. Though the Land had rarely frightened him, he experienced a shiver of dread.

Here and there on the most distant ridges, Kannujaq spotted

inuksuit

âstacks of flat stones, carefully piled so as to resemble people when their silhouettes were viewed against the sky. And Kannujaq knew who had made them. His grandfather had said so. The inuksuit were the works of

Tuniit,

a shy and bizarre folk who had occupied the Land long before the arrival of Kannujaq's family. It was said that the strength of the Tuniit was great. Hauling a stone the size of Kannujaq himself was as nothing to one of them. That was just as well, since the Tuniit relied on stones to hunt. Since the inuksuit resembled people standing on the hills, caribou took paths to avoid them. Every year, when the caribou did so, the Tuniit supposedly took advantage of their route, herding the animals into zones where they could be slaughtered. The Tuniit hunted with bows, as Kannujaq's

own people did. Kannujaq's grandfather had seen one of the Tuniit hunting sites: all bones on top of bones. Some new. Others quite old. It had seemed clear that the Tuniit had hunted in their weird way for generations.

Kannujaq frowned, recalling his grandfather's stories, and not even the Land's glory was able to pull his thoughts away from the Tuniit. He wondered about the Tuniit hunting style. It meant that they stayed in pretty much the same place. Maybe even year round. That was a strange notion to Kannujaq. His people were always travelling, exploring for exploration's sake, family members splintering off to found their own little groups along new coasts. For generations, travel, a hunger for the unseen, had been the great drive of his folk. Ringed seals. Lovely whales. Stinky walruses. All the creatures of the coastsâthese made up food and tools to fuel a search whose sole purpose was life itself. Life was a joy, and one grand hunt.