Sleeper Agent (23 page)

Authors: Ib Melchior

Tags: #Action & Adventure, #Mystery & Detective, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fiction, #Literary Criticism, #English; Irish; Scottish; Welsh, #European

He believed her. He placed the harmonica—the goddamned

Fotzhobl

—on the table. “Keep it,” he said.

He looked at the shaken girl. “Your father is all right,” he said. “Nothing has happened to him.”

The girl’s eyes opened wide. She leaped to her feet and rushed from the room, followed by her mother.

Rosenfeld stood in the barnyard with Burghauser.

Both the women were hugging the fanner unashamedly. He looked uncomfortable at the display of emotion in front of strangers.

Tom went up to Rosenfeld.

“Did it work?” the sergeant asked eagerly.

“Yes.” Tom did not feel like elaborating. “It worked.”

“I may have something, too,” Rosenfeld said importantly.

Tom looked at him sharply. “What do you mean?”

“Well, you told me to take a look around. So I did.” He nodded toward a shack in a far corner of the yard. “That’s the chicken coop,” he said. “There’s a chest in there. Like a footlocker. They use it as a feed bin. It’s got a number stenciled on it Like an ASN. It could be the army serial number of some Kraut, couldn’t it? And it could have come from the Schloss Ehrenstein place, right?”

“Right!” Tom was already striding toward the chicken coop.

A few sleepily roosting hens put up a cackling protest when he flung open the door to the coop and began to shoo them out. The close air in the shack was heavy and sour, and the dirt floor was moist and slimy with chicken dung. In a corner stood the feed box. Tom recognized it at once as a German soldier’s field chest. It was scratched and smeared with dirt. But the army serial number could be plainly read.

Tom turned to Rosenfeld. “Get that damned farmer over here on the double!” he barked.

Burghauser stood awkwardly in the doorway to the chicken coop.

Tom pointed to the chest. “Where did you get that?” he demanded bitingly. “Schloss Ehrenstein?”

The farmer stared at the chest as if seeing it for the first time. Slowly he nodded his head. “Yes,” he said. “I had not remembered it.” He shook his head in worried wonder. “Yes . . . The feed bin.”

“Empty it!”

The farmer sloshed across the slimy floor. With his big callused hands he took hold of the chest and up-ended it. The dry chicken feed poured out onto the wet floor, slowly soaking the moisture from the fresh dung.

“Bring it here!”

The fanner placed the chest at Tom’s feet

He examined it. The inside was caked and filthy with old feed. The chest was indeed empty. He bent down to look closer. And he saw it In the corner a small bit of blue paper was caught in a crack. He pried it loose. It was crusted with dried chicken feed. Carefully he cleaned it off. It was the torn-off stub of a theater ticket.

“Regensburger Stadttheater,” he read. “

Parkett Links.

Row five, number twelve. March seven, 1945.” He turned it over. On the back he could make out a penciled note: “791 SG.” It meant nothing to him. Absolutely nothing.

It was dusk when Tom stood in the overheated, stuffy

Bauernstube

of a small farm on the outskirts of the village of Falkenstein, some fifteen miles northeast of Schloss Ehrenstein.

For almost ten grueling hours he and Sergeant Rosen-feld had interrogated a host of farmers and villagers in the area around the estate. One had led to another. And another. And another. He had lost count

He had scrutinized beat-up, dented cookware and kitchen utensils, mismatched boots with worn-through soles and mended socks. Ripped and empty sandbags, odd-sized leather straps and a dog-eared copy of

Mein Kampf.

All looted from Schloss Ehrenstein. All put to some use by the looters. He had found nothing.

He had examined odds and ends of uniform clothing. Some of it he had literally taken off the backs of the new owners. Though he knew it was futile, he had searched through every pocket He’d had to do something. There had been nothing.

He had inspected a Waffen SS belt with a broken buckle, a rusty bayonet, its tip snapped off. Torn blankets. A boxful of spent cartridges, a collection of sundry useless hardware—and a goddamned

Fotzhobl!

Nothing!

The woman who stood trembling before him, flanked by two young boys barely in their teens, stared at him fearfully. She was alone on the farm. Her husband had been killed in the Rundstedt offensive at Bastogne. She and her two boys had run the farm, with the help of two foreign laborers who had long since run off.

On the table in the room lay an assortment of items. A box of uniform buttons. Two large wooden ladles, one of them split A sweat-soaked uniform cap, its insignia gone. And a notebook. It was empty. The first several pages had been ripped out. “That is all you took from Schloss Ehrenstein?” Tom asked.

The woman nodded.

Sergeant Rosenfeld came in from the yard. The woman turned to look at him apprehensively. “Nobody else around,” he said.

Tom nodded. He addressed the woman. “You realize that if you are keeping anything back, you will be severely punished?”

She looked back at Tom. For the shadow of a split second a look of black hatred flared in her frightened eyes. Or was it stark fear? “There is nothing else,” the woman whispered, her voice barely audible.

“Good.” He fixed her with a baleful stare. “All the same, we shall take a look through the house. You come with me. The boys stay here.” He turned to Rosenfeld. “Keep an eye on them.”

The woman tensed. For a moment she seemed ready to uncoil in violence. Then she meekly let go of her boys.

Deep in his own bleak thoughts, Tom did not notice.

The woman followed him from room to room in the little farmhouse as Tom searched the family’s belongings thoroughly. He found nothing of value. To him or anyone else.

At last they came to the cramped and cluttered attic. Dusty, dimly lit from one small dirt-grimed window, it was filled with junk. Under a stack of old yellow newspapers he found a large leather-banded trunk with heavy metal hinges and locks.

He looked at the woman. “What is in that?” he asked.He tried to read the grim set to her face, the dark look in her eyes. Hate? Fear? Guilt?

He had a quick impulse to chuck the whole goddamned scene. Take the poor woman down to her sons and get the hell out of the place. “Open it,” he said.

Without a word she obeyed. The trunk was not locked. On top of a pile of clothing was a heavy gray coat, a uniform coat He lifted it out. He looked inside the collar. The label was still there: “

Vom Reichsführer SS befohlene Ausführung. RZM.

” The mark of the official SS uniform.

“Who does this SS coat belong to?” he snapped angrily. “Your husband?”

Suddenly the woman erupted in a terrified stream of words. She was deathly afraid. “No! No, Herr Offizier!” she cried pitiably. “We did not steal the clothes, Herr Offizier. They were given to us. By an officer. From Schloss Ehrenstein.”

She rubbed her tearing eyes fiercely with work-hardened knuckles. “I . . . I meant to tell you. I really did. But I was afraid you would take the clothes away. And we need them. . . . the boys . . . we need them so badly. For the winter.

Bitte! Bitte!

” she pleaded. “Please, do not take them away from us!” She put her fists to her face and sobbed.

Tom’s hands were already searching through the pockets of the SS coat. There! His probing fingers found something. A small piece of crumpled paper torn from a notebook. Quickly he smoothed it out. A few words were written on it in cramped Gothic script. In the dim light he could not make them out. He walked to the small dirt-streaked window and held the slip to the waning light, his back to the softly weeping woman.

Suddenly he heard the faint, sharp clang of metal striking metal. Instantly he whirled around. It saved his life.

The first shot grazed his arm at the shoulder, barely breaking the skin. The second went wild.

He lunged at the woman, who was standing wild-eyed, a blue-black Luger held in front of her. His racing mind took in the scene as he hurled himself at her: the disarrayed clothing in the trunk that had hidden the gun, the gleaming hinge it had hit in the haste of hauling it from its hiding place.

His hand struck the woman’s arm a numbing blow. The Luger flew from her hand to clatter along the dusty floor. He stared at her.

She was oblivious of her arm hanging useless at her side. Her burning eyes blazed their hatred as she returned his stare. “You killed my husband, you

Ami

swine!” she hissed venomously. “You—killed—him!”

Rosenfeld came bounding up the stairs, his gun ready in his hand. Instantly he realized what had happened. He swung his gun to cover the defiant woman.

Behind him the two young boys came scrambling up. They flung themselves at their mother. She clasped them tightly to her.

Tom stared at her. He had felt sorry for her. He had felt guilty for having to treat her roughly. He had misread all the little signs she involuntarily had given him. Fear for hate. Guilt for vengeance! Because of his own goddamned mixed-up German-bastard feelings! He felt a mushroom of rage well up in him. A rage against himself. He had been one hell of a goddamned stupid shit! No more. To hell with the fucking Krauts!

He went back to the window. The light was getting bad. Intently he peered at the slip of torn paper. A name. An address.

Regensburg. Like the theater ticket.

He started for the stairs.

Rosenfeld picked up the Luger. “What about her?” he asked, nodding toward the woman.

Tom stopped. He did not turn. “Leave her.” For a moment he stood still. Then he looked back at the defiant woman clutching her two frightened boys to her. “Keep the clothes,” he said.

Tom was sitting at one of the tables in the

Gaststube

of Gastwirtschaft Bockelmeier. He was making Straubing CIC HQ his base of operation for the time being. It was late, but he wanted to get his report out of the way. Early next morning he intended to go where his only clues were leading him: Regensburg.

He had briefly debated with himself if he should check with Major Lee first Regensburg was after all in the XX Corps area. He had lost the debate. He had long since learned that if you don’t ask questions you can’t get no for an answer.

Anyway, both XX Corps and his own XII Corps were part of Third Army. That ought to be good enough—especially for an “unorthodox” caper!

The door from the street opened and Agent Buter came in. He spotted Tom. “Hey, Jaeger!” he said. “Have you heard the news?”

“What news?”

“I see you haven’t,” said Buter. He sauntered over to Tom. “Let me be the first to enlighten you, my boy.”

“Be my guest.”

“I’ve just come from CP. They’ve been monitoring the Kraut radio.” He drew himself up importantly. “Der Führer is kaput!” he announced. “Dead!”

“Hitler?” Tom was startled.

“How many Führers do you know? According to the Hamburg radio—and I quote with great pleasure—Hitler died a hero’s death in defense of Berlin! Yesterday.”

“That’s a crock of shingles.”

“Undoubtedly. But the son of a bitch is just as dead.” He started for the kitchen. “Don’t strain yourself, buddy boy. The war is practically over.” He disappeared through the door.

For a moment. Tom sat in silent thought. At long last the end was near. He found it hard to realize. In a little while the fighting would be over. The complicated and chaotic time of settling in for occupation duty would begin. There would be sweeping changes in all CIC and other intelligence operations. It would be a time of confusion. A time when it would be all too easy for a Sleeper Agent—a Rudi A-27—to disappear!

He returned to his report “86 Wenderstrasse, Regensburg,” he wrote.

He stared at the words. Regensburg. . . . Somewhere in that city of some 120,000 Germans were the answers to his quest He was certain of it. Tomorrow he would find out.

9

Regensburg—the ancient city of Ratisbon—had a bloody history of war and violence dating back to the pre-Christian Celtic settlement of Radispona.

Conquered by the Romans and fortified by Marcus Aurelius, it had become the Roman center of power on the upper Danube and had been renamed Castra Regina. Part of the Porta Praetorius, built in

A

.

D

.

179, still stood. The age-old massive limestone blocks and slabs gave an indestructible look to the town—belied by the devastation surrounding it.

Charlemagne captured the city in 788, and by the thirteenth century it had become the most flourishing town in southern Germany, an important stopover for the crusaders on their way to their holy wars.

Plague and capture and pillage razed the city during the Thirty Years’ War, and by 1809, when Napoleon’s invincible troops stood before her gates, the town had suffered through seventeen disastrous sieges during her strife-torn life. Once again she was reduced to ashes.

As Tom and Sergeant David Rosenfeld drove into the bomb-battered city it was glaringly obvious that history was repeating itself. The great Messerschmitt factories, targets of the massive Allied air raids, lay in ruins. On their way to town Tom and Rosenfeld had passed the last desperate attempt of the Luftwaffe to manufacture the much needed aircraft: an open-air assembly line of ME-262s strung through a field, hidden in a forest east of town.

The SS troops had blown the great Regen and Danube bridges—including the famous twelfth-century stone bridge, the Steinerne Brücke, an architectural marvel of the Middle Ages—in a wanton, futile attempt to stem the American tide. But the town wore her battle scars as proudly as a Heidelberg student his dueling scars.

The city had been taken six days before by the 65th and 71st Divisions, and as Tom and Rosenfeld drove through the narrow winding streets on their way to CIC HQ, civilians and soldiers alike all but ignored them.

On the famous Gesandtenstrasse—Ambassadors Street—damage to the old historic buildings was minor. The houses still bore the colorful coats of arms of the foreign representatives who had occupied them in happier days.

Tom glanced at the street map in his lap. Wenderstrasse was nearby. He turned to Rosenfeld. “Stop here,” he said.

Rosenfeld looked at him in surprise. He pulled the jeep over to the curb and stopped.

“We can save some time,” Tom said. “I want you to go on to CIC. Find out from them anything they have on Schloss Ehrenstein, on Sleeper Agents—and on KOKON.” He looked down the street. He dismounted. “I’ll take a look at the Wenderstrasse place,” he said. “I’ll meet you at CIC later. Take off!”

Rosenfeld drove off.

Tom stood alone in Gesandtenstrasse. The German civilians passing him made a more than necessary detour around him. He noticed they made a point of not looking at him. He glanced around him.

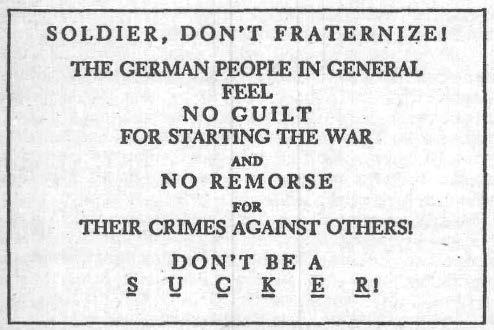

On the wall behind a US Army flyer had been tacked up:

He looked away. He had never felt as conscious of his native heritage before. Furtively he watched the Germans hurrying by. None of them paid any attention to the flyer. Nor to him. He started to walk toward Wenderstrasse.

Wenderstrasse 86 was a four-story apartment building precariously propped up with large wooden beams. The ground floor was occupied by boarded-up shops; the masonry walls were chipped and gouged by shrapnel. The building had received a direct bomb hit at one corner, shearing it away, exposing the layers of empty rooms like giant honeycombs.

Tom went to the door of one of the shops. The display window had been boarded up except for one small square covered with a piece of cracked glass. He knocked on the door. He waited. He knocked again.

Finally a man’s voice called, “

Wer ist da?

—Who is there?”

“I am looking for Gerti,” Tom answered.

A man’s face appeared at the cracked windowpane. It peered suspiciously at Tom. It withdrew. A middle-aged man with short gray bristly hair opened the door. He looked at Tom’s uniform, a mixture of hostility and contempt mirrored on his sullen face. “Fräulein Grunert is in the rear,” he said grumpily. “Last door on the right.”

So that’s her name, Tom thought. He filed it away.

“You can come through here this time,” the man continued, resentment coloring his voice, “but next time use the other door. Like the rest of them do.” He stood aside to let Tom pass.

Tom felt his unfriendly eyes upon him. “Thank you,” he said. He wondered what “the rest of them” wanted with Gerti Grunert. He had a sudden uneasy feeling that he was about to embark on a wild-goose chase—without a shotgun.

He followed the querulous man’s directions, walked down a badly lit, musty smelling corridor and found himself facing a door from behind which came muffled music from an obviously old and tinny phonograph. He tapped lightly on the door.

A feminine voice called out in passable English, “Come in, darling!”

He entered the room. He knew at once where he was. He could taste his disappointment. The room was lighted with red and amber bulbs, casting a ghastly orange glow over everything. Heavy flowered drapes were drawn across the two windows, and the air was heavy with cheap perfume. A large bed strewn with multicolored pillows dominated the room, and an old dilapidated gramophone on a mirrored dresser was grinding away on an out-of-date

Schlager

—a hit tune whose time long since had come and gone. A wad of newspaper had been stuffed into the loudspeaker to muffle the tone.

Gerti Grunert was a girl in her middle twenties possessing a certain brazen beauty. Looking at Tom with frank appraisal in her dark eyes, she uncurled herself lazily from the bed and stood up to face him. She wore a flimsy, not-too-clean pink negligee over an open-lace black bra, black lace panties—and knee-high black patent leather boots.

She shook her luxurious long brown hair seductively, planted her booted legs firmly, slightly apart, on the floor, put her hands on her hips and leaned her pelvis provocatively toward Tom. She gave a little laugh—too shrill to be pleasing. “Who are

you?

” she asked. “I do not know you.”

Brazenly she looked him up and down, “But you are cute.” She laughed again. “Very cute,

Schatzi!

You want to stay with me?”

It was a question to which Gerti obviously already knew the answer. She shrugged her negligee off her bare shoulders and sat down on the bed. “How did you come here,

Liebchen?

” she asked. “You have perhaps a good friend who will not mind sharing?” She laughed. “

Ist gut!

—That’s fine!”

Tom thought fast. His first Regensburg lead was not exactly what he had anticipated. But Gerti was obviously an enterprising young lady. It had not taken her long to round up a clientele among the GI’s in town—fraternization or no fraternization.

She must have been in business for some time. Her name and address scribbled on the slip of paper he’d found in the coat from Schloss Ehrenstein proved that. She would have entertained personnel from the castle in the past. Perhaps she

did

have information he could use. He had to decide how best to get it out of her. And decide fast.

He scowled at her. “You are mistaken, Fräulein Grunert,” he said coldly. “I am not here as a customer.”

The inviting smile at once disappeared from the girl’s lips. Narrow-eyed, she stared at Tom, suddenly worried.

She is not as pretty as she appeared to be at first, Tom thought Her face is too hard. Too crafty.

“What do you want with me?” she asked testily.

“It depends,” he said. “On you.”

He saw the quick flicker of calculation in her eyes. What did he want? Would he make trouble? Or was he simply out to get a free lay? She was shrewd. There was something else.

She stood up. She looked closely at him. “You are not a regular

Ami

soldier,” she said accusingly. “I know what their uniforms are like. Their emblems and their insignia. Officers and enlisted men. I know.” She could not help sounding a little boastful. “You are”—she pointed to the single US emblems on his shirt-collar tabs—“different.”

He nodded. “I am.”

She gave him a guarded look. She licked her red lips. “How . . . different?”

“I am an officer in the United States Army Counter Intelligence Corps,” he said calmly.

Gerti’s eyes grew veiled. “Secret police . . .” She turned her heavily made up eyes full upon him. “What do you want with me? I have done nothing.”

“You are aware, I am sure, of the Army’s non-fraternization policy, Fräulein Grunert,” he said sternly. “A policy you are flagrantly violating.”

She shrugged. She picked up her negligee and placed it around her shoulders. “The American soldiers,

they

come to

me,

” she said brazenly. “I treat them well. Would you have me resist them?”

“I’m not interested in your activities,” Tom said, his voice flat “I want some information.”

A quick flicker of apprehension flashed in the girl’s eyes. “What . . . kind of information?” she asked suspiciously.

“How long have you been in business here?” he asked coldly.

She glared at him angrily. “Why should I tell you?” she demanded.

He smiled unpleasantly. “I think, Fräulein Grunert, I think you can figure out for yourself

why,

” he said.

She frowned. She suddenly looked ridiculously young. “A year,” she said tonelessly. She shrugged. “A few months more.”

“You entertained customers from the Wehrmacht?” The SS?”

She nodded.

“Were any of the men stationed at a place called Schloss Ehrenstein?” he asked.

Gerti looked up quickly. The look of alarm flitted through her eyes once again. She stared at Tom wide-eyed.

“Well?” he snapped.

“Yes,” she whispered. “I . . . I think so.”

“

Think?

” He fixed her with a scathing look.

“I mean . . . yes,” she said quickly. “I know some boys told me they stayed at the old castle.”

“That’s better,” he growled.

“But I know nothing else about them. Any of them.” She gave him a quick glance. “What about them?”

Tom’s gruff manner softened. He sat down beside her. “I’ll be frank with you, Fräulein Gerti,” he said earnestly. “I have a German suspect in custody. A young soldier. He has been accused of serious war crimes. He denies being guilty.”

He looked at the girl. His voice grew confidential. “He says he has a brother. A brother who can prove him innocent. We do not want to punish the innocent, Fräulein. I should like to find this man’s brother.”

He watched the girl. She was listening intently to him. She shrewdly realized that the pressure somehow had shifted away from her. She wanted to keep it that way.

“This brother was supposedly stationed at Schloss Ehrenstein,” Tom continued. “During the last year or so. His name is Rudi Kessler. Did you know him?”

Gerti shook her head. “I do not remember.”

Tom suddenly returned the grim scowl to his face. Abruptly he stood up. Stiffly he glared at the girl. “As you wish, Fräulein,” he said in a tone of dismissal.

Quickly she rose with him. “What the devil do you want from me?” she flared. “I cannot remember every cock who paid his twenty marks! Certainly not the marvels from Schloss Ehrenstein!” She tossed her head. “

Es war immer eine Blitzsache,

” she said scornfully. “It was always a blitz affair with them.”

“Blitz affair?”

“They were always in such a damned hurry.”

“Why?” he asked sharply.

“How do you expect

me

to know?” she snapped.

Tom said nothing. He merely looked at the girl, a little icy smile on his lips. Gerti looked frightened, her bravado fading away. She sank back down on her bed. “They . . . they only stopped by here to be with me on their way to someplace else,” she said. “They were not supposed to.”

“Where?”

She frowned at him apprehensively. “I do not know. Some meeting place. Some house . . . on Stiergasse.”

“Number?”

She looked up at him, her eyes troubled. “Look,” she said. “That is all I know. All. I swear it. I do not know any number. Believe me! Why should I lie to you? What is it to me?” She tried to wet her crimson lips again, but her mouth was dry.

Tom looked at the frightened girl. Her pallor of fear made the rouge on her cheeks look clownishly grotesque. He felt deeply sorry for her. But she

had

given him his clue!

“All right, Gerti,” he said. “I believe you. I believe you have told me what you know.”

He turned and walked from the dismal room, leaving the girl sitting on her bed. Her all-important bed. He could hardly wait to dig into his pocket and whip out the little slip of blue paper that seemed to be burning a hole in it. A theater ticket stub from the Regensburger Stadttheater.

The penciled note on the back read, “791 SG”—791 Stiergasse!

Tom stood staring at a huge pile of rubble that once had been a building. What kind of a building was impossible to tell. The destruction was total. And recent. The grass and weeds overgrowing most of the rubble heaps left from the bombings were only beginning to take hold.