Sleeping Around (34 page)

The impact of the Soweto protests reverberated through the country, drawing the world's attention to the plight of black South Africans, resulting in international sanctions and eventually the end of Apartheid.

Outside the museum was a memorial stone where Hector Pieterson had fallen.

âThat could have been my mum,' Walindah said. âShe was a lucky one.'

We drove around the corner from the museum to Vilakazi Street, a normal suburban street with one mighty claim to fame. This small street has been home to two Nobel Peace Prize winners: Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Nelson Mandela's old house is now a museum run by Winnie Mandela. Walindah told me that she lives in a secure mansion two blocks away and can occasionally be seen cruising the area in a white Mercedes with bulletproof windows.

Inside Mandela's house the walls were adorned with photos and tributes, including countless honorary degrees and a formal apology from America's Central Intelligence Agency for its involvement in his persecution. To be frank, though, I thought most of the house, like the jackal bedspread and Winnie's army boots at the end of the bed, was all a bit tackyâparticularly the hawkers out the front selling Nelson Mandela T-shirts, Nelson Mandela mugs and plastic jars filled with âdirt from Nelson Mandela's backyard'.

Archbishop Tutu still lived in his grey, two-storey house, but he must have felt a little jealous. No one was selling Archbishop Tutu mugs out the front of his house.

âThis is the most dangerous part of Soweto,' Walindah said, as we later drove through the middle of the ghettos of Zola and White City past impoverished street traders with scant arrays of truly pathetic produce laid out before them on the sandy footpath in front of their homes. Their âhomes' were self-made shacks of corrugated metal and wire.

âThis area is notorious for gangs of armed car hijackers,' Walindah said without even a hint of panic in her voice.

âShould we be here in a . . . in a car then?' I said with quite a bit more than a hint of panic in my voice.

âIt's okay,' Walindah assured me. âBut, we'd be mad crazy driving through here at night.'

I wasn't that surprised when Walindah then said, âThe tour buses don't come here.'

âWhere do the tour buses go?' I asked.

âI will show you the tourist slums,' Walindah said brightly.

We pulled into the small gravel car park for the âtourist slums' next to a small tour bus and a few souvenir stalls. One stall was selling âAuthentic South African wood carvings'. Most of the woodcarvings were of giraffes and looked suspiciously as if they came from the Wamunyu collective in Kenya.

Walindah arranged with a local boy named âBrilliant', after a somewhat hefty donation from me, to view the shack that he shared with his mother and sister. Although I knew the âdonation' was well needed, I felt uncomfortable about having a gawk at a stranger's poverty.

âIt's okay,' Walindah whispered as we were led down a dirt track lined with tiny shacks that had stones holding the roofs in place and were covered in plastic sheeting to prevent the rain turning the dirt floors to mud. âThis is how they make their living.'

Women in large bright dresses flashed us large bright smiles as we wandered past yards filled with rows of maize drying in the sun next to piles of rubbish and old rusted cars. Brilliant's shack was painted bright red and had lovely lace curtains in the window. Inside, the family shared a few square metres with one table and one bed. With no electricity or running water in the area, the house was heated with a paraffin stove and they used buckets for showers. They did have a television set powered by a car battery, though. âSee, they can watch the soaps, too,' Walindah said.

On the way back to the car we strolled past a church, which was more like a large tin shack. We only knew it was a church because we could hear the service inside, where a gospel choir was singing joyous hymns in Xhosa and English. We peeked through a gap in the door and were immediately dragged in and welcomed by a grey-bearded priest in a bright yellow flowing robe and large red cape decorated with white tassels. Although the room was dark it was virtually aglow with a flock of women in long white robes and white hats singing, wailing, clapping their hands and swaying with an outpouring of devotion. It was like a sauna in the tin shed and after a few minutes the sweat was pouring off me in buckets.

When we stepped back onto the street, Walindah told me about the time Bill Clinton came to visit Soweto and went to a church service. âThe priest gave the sermon,' Walindah said with a giggle â. . . about adultery.'

By way of contrast, we then drove to Diepkloof where âthe millionaires and crime bosses of Soweto live'. This was the posh part of Soweto, with three-storey mansions behind high walls and electric gates that looked just like the fortress homes of the white suburbs I'd passed in the city. All the roads were freshly tarred and there were BMWs in the driveways and well-dressed children playing in the gardens.

There were more glistening BMWs and chrome-plated Toyota four-wheel drives lining the street outside Sakhumzi Restaurant, a few doors up from Archbishop Tutu's house, where we stopped for dinner. We sat outside in the garden, where young men in designer suits mixed with young men in trendy ghetto gear.

âWould you like me to order some traditional South African food?' Walindah asked, after we were shown to our table.

Our traditional South African entrée was a plate of fat black slimy worms that were âgently simmered' and came served with peanut butter and tomato relish. I may have grimaced a bit because Walindah said, âThey're not really worms, they're Mopani worms which are actually the caterpillars of the emperor moth.'

Oh, that made me feel much better.

âMopani worms are very nutritious,' Walindah said, as I very, and I do mean very, tentatively picked up a worm. âThey are sixty per cent protein and have lots of calcium,' Walindah added. When I popped the worm into my mouth, the first crunch wasn't so bad. It tasted like burnt sausage. Then the second crunch let loose the slimy insides which tasted exactly as I had feared a worm would taste like. As if someone had blown their nose into my mouth.

It wasn't until I'd eaten a couple that I noticed Walindah hadn't touched them.

âI'm not eating them,' she said, screwing up her face. âThey're disgusting.'

I didn't think I could stomach the traditional main course, either. It was

umgodu

, otherwise known as stomach. The plate of white rubbery-looking tripe came with

umxushu

(beans), wheat bread and crushed corn. The crushed corn and beans were delicious. I pushed the tripe around the plate, so it looked as if I'd eaten some.

âCan we go to a

shebeen

?' I asked Walindah when we got back to her house. I'd noticed that there was a

shebeen

(which is an illicit bar) only a short walk up the road from Walindah's house.

When we got to the

shebeen,

Walindah said, âI won't stay. This is a man's bar, but I will find someone to look after you.' She scanned the small crowd sitting out the front and walked over to a young fellow with arms as thick as my thighs. âHe is my friend's cousin. He will look after you and walk you home later,' Walindah said. âIt is probably not a good idea to go inside,' Walindah added before she turned to head back. âThere are a lot of drunk crazy people inside.'

As soon as Walindah left, my new friend said, âCome inside.'

When I walked in many of the patrons stared at me as if to say âWhat are you doing here?' It wasn't an angry âWhat do you think you are doing here?' It was more of a âHow have you managed to get so completely lost as to end up here?' Not surprisingly I was the only

umlungu

or whitey in the

shebeen

, and probably the first to ever to step foot into the bar.

One man with bloodshot eyes and sporting a blue work suit staggered over and shook my hand. âI am your friend,' he spluttered.

We grabbed a beer and sat outside and I was immediately surrounded by a group of young men. They were all talking at once, asking me to buy them beer, and if I âwant an African girl'. Two handed me bits of paper with their addresses on them so I could write to them and then âsponsor' them to come to Australia. My âminder' went back inside the bar, leaving me with a large but quite effeminate young fellow to âlook after me'. âDid you know that South African men have the biggest dicks in the world?' my new minder said, giving me a wink.

âYou're back early,' Walindah said. I hadn't even waited for my minder before trotting rather briskly back to the house as soon as I'd finished my beer.

âOh, I have to get up early to get to the airport anyway,' I muttered.

â

Survivor

is just about to start if you'd like to watch it,' Walindah said, before turning back to the TV.

17

âOur colony of cows will greet you at the front gate . . . along with our 24hr security guard who tends to nod off during his shifts.'

Penelope Walker, 26, New Delhi, India

GlobalFreeloaders.com

âWhere is the house?' my grumpy taxi driver asked after he'd driven around the same block four times.

âI don't know, I haven't been here before.'

âI don't know, either,' he huffed before dumping me in the middle of a dark and dusty lane somewhere in the back streets of Kalkaji in South Delhi.

The houses and apartment blocks in the street were hidden behind high brick walls. But that wasn't the problem. The problem was that there were no numbers. I really had no choice. I would have to ring every bell until I found the right block. I wasn't going to be very popular either. It was after midnight. With a large sigh I tottered a few metres over to the nearest apartment and rang the bell next to the high iron gates. There was no answer so I rang it again. And again. When a somewhat groggy security guard finally appeared, I asked, âDo a Penelope and Sarah live here?'

âYes.'

Yes!

I'd found it on my first go and this was the famed security guard who âtended to nod off '.

Penelope and Sarah don't sound like Indian names, but that's because their owners were two Australian girls from Sydney working in Delhi. When I stumbled upon their profile I decided it might be interesting to see what expat life was like in one of the biggest, noisiest, smelliest, hottest, dirtiest and most crowded cities in the world. Plus I couldn't pass the opportunity to stay in a palatial mansion:

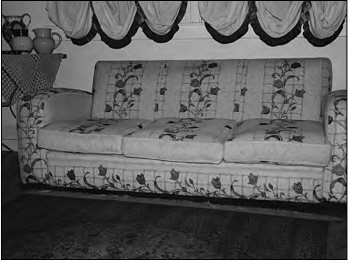

Comfy velvet bottle-green couch in a palatial mansion with marble floors and high ceilings. We're working in a call centre in Delhi full time, and we go out for dinner or drinks pretty much every night of the week because everything here is so cheap.

Penelope, 26

I sent out some requests to a few locals as well in case the comfy velvet bottle-green couch was otherwise occupied. It was a pity I'm not a female, though, because I found some other great potential hosts:

Our house is not in an excellent shape, however all the conventional facilities are there. I live with my family so you have to be a girl and you have to behave. I also expect decent standards of hygiene from you (ie. no piddling on the floors).

Shashank, 25

Gender of Guest: Female only Sleeping place I can offer: My King Bed with me!

Suresh, 43

I'd like to spare room with some not smoking girl. i can provide a lot of things from cooking dishes till mattress and pillows. illegal sex is strictly not allowed.

Praveen, 30

Penelope and Sarah welcomed me at the door of their apartment. âWe're so happy to see you,' they giggled. âWe're a bit drunk.' Both girls were incredibly tall and slim. Sarah had blonde hair and blue eyes and Penelope had freckled cheeks and long auburn hair. They couldn't have stood out more in India if they tried. âCome on in,' Penelope said, grabbing my hand and escorting me down a long corridor to a dimly lit lounge room. The lounge room did have marble floors and high ceilings, but it wasn't looking very palatial. Littered around the room were empty beer bottles, pizza boxes, overflowing ashtrays and empty chip packets. And slouched on my comfy velvet bottle-green couch behind a thick haze of smoke were two fellows smoking a whopping joint and tipping ash all over the comfy velvet. I was introduced to âJohn from England' and âthe Dutch guy'. They didn't look as if they were leaving, or capable of leaving, my âbed' anytime in the near future.

Then Penelope said something that made me want to hug her with joy. âYou don't have to sleep on the couch,' she said. âWe've got you your very own apartment.' Another expat had recently moved out of one of the upstairs apartments, so the girls had sweet-talked the security guard into unlocking it for a âspecial guest'.

On the way up to the apartment Penelope told me about her job in Delhi. Both girls and âJohn from England' worked in a call centre for a UK-based travel agent selling Australian package tours. âIt suits us perfectly,' Penelope beamed. âWe start at one in the afternoon and finish at nine.' The reason for the odd hours was that they worked on UK time. Callers were then under the assumption that they were calling from somewhere in the UK. Penelope had been manning the phones for six months, and had only recently talked her best friend Sarah into joining her in India. âI'm here for another six months then I'll go home and get a real job,' Penelope said. âThe job here is not bad, though. We have a driver who picks us up and drops us off every day and the company has a chef who makes us curries for dinner every night.'