Smuggler Nation (35 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Decriminalization was therefore achieved through medicalization; the rationale of disease prevention provided the cover for pregnancy prevention. Contraceptives were not removed from U.S. obscenity statutes until 1970, a century after the Comstock Act. And until 1971 it was still illegal (and thus considered smuggling) for a layperson to import contraceptives.

56

Only after the sexual revolution of the 1960s did access to birth control come to be viewed as not just a medical necessity but also as a reproductive right.

The “White Slave Trade” Moral Panic

The only thing that enraged morality groups more than selling smut was selling sex. And not only was there plenty being sold, it was both highly visible and foreign-looking. From New York to San Francisco, the brothel business in urban America was flourishing, and many of the prostitutes were newly arrived immigrants. This coincided with the rapid growth of cities, filled by record waves of new immigrants, an increasingly restless and mobile population, shifting sexual mores, and rising public anxiety over the disorienting speed of change. This combustible mix was the backdrop for a full-blown nationwide panic over the “white slave trade” in the first decade of the twentieth century.

In following a familiar pattern, accusing fingers once again pointed at the new arrivals. And it wasn’t just their sheer number that was so unsettling (some thirteen million new immigrants between 1900 and 1914); it was also where they were coming from: increasingly from eastern and southern Europe, which meant more “undesirable” Catholics and Jews. A congressional commission set up in 1907 warned of the growing connection among immigrants, vice, and crime: “The vilest practices are

brought here from continental Europe” and “imported women and their men” were corrupting America with “the most bestial refinements of depravity.”

57

Jewish and French pimp organizations were singled out for the most blame.

58

Sensationalistic accounts in the popular press further fueled fears of an invasion of vice. Writing for

McClure’s Magazine

, the muckraker George Kibbe Turner gained instant national attention in April 1907 when he reported that a “company of men, largely composed of Russian Jews,” supplied most of the women for Chicago’s brothels, and that “These men have a sort of loosely organized association extending through the large cities of the country, the chief centers being New York, Boston, Chicago, and New Orleans.”

59

Turner gained even more attention in November 1909 with another article in

McClure’s

, this time claiming that New York City had become “the chief center of the white slave trade in the world.” This massive illicit trade, he claimed, came from Europe and was now so deeply entrenched in New York’s immigrant neighborhoods that the city’s sex traders were exporting enslaved women to all corners of the globe.

60

And the victims were not only poor immigrant girls but also naïve and innocent “country girls”—wooed to the darkness of the city by slick and shady foreign men. Turner offered startling details even if very little actual evidence; but no matter. The story stuck in the national imagination because it reaffirmed and played to deep-seated anxieties and fears. Variations of the same storyline proliferated in articles and books across the country, generating a cottage industry of white slave trade horror stories.

61

Edwin W. Sims, the U.S. attorney in Chicago, added an authoritative voice to the chorus of alarm bells. In 1909 he confidently wrote, “The legal evidence thus far collected establishes with complete moral certainty the awful facts: That the white slave traffic is a system operated by a syndicate which has its ramifications from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific ocean, with ‘clearing houses’ or ‘distribution centers’ in nearly all of the larger cities … that this syndicate … is a definite organization sending its hunters regularly to scour France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Canada for victims; that the man at the head of this unthinkable enterprise it [

sic

] known among his hunters as ‘The Big Chief.’”

62

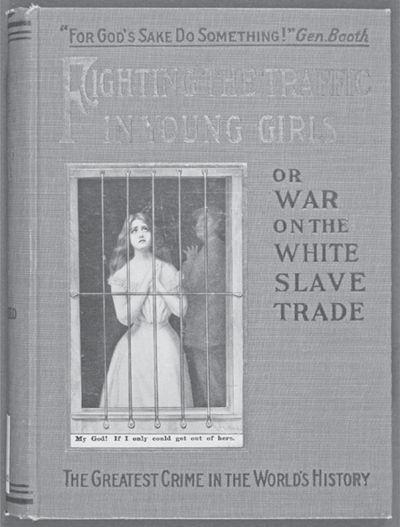

Figure 11.4

Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls, or War on the White Slave Trade

. The provocative cover of a popular 1910 book by Ernest A. Bell depicts a young girl enslaved in a brothel and watched over by a shadowy figure (Yale University Library).

In late November of that year, President Howard Taft was briefed by Sims, along with Representative James R. Mann of Illinois, the chairman of the House Committee on Foreign and Interstate Commerce. At the end of the meeting, Mann announced to the press that

investigations “have disclosed a situation startling in its nature as to the extent of the traffic in young girls, both within the United States and from France and other foreign countries. Most of these American girls are enticed away from their homes in the country to large cities. The police power exercised by the state and municipal governments is inadequate to prevent this—particularly when the girls are enticed from one State to another or from a foreign country to the United States.”

63

In his first State of the Union Address the next month, Taft pointed to the “urgent necessity for additional legislation and greater executive activity to suppress the recruiting of the ranks of prostitutes from the streams of immigration into this country,” concluding that “I believe it to be constitutional to forbid, under penalty, the transportation of persons for purposes of prostitution across national and state lines.”

64

The

New York Times

chimed in with its support, editorializing that the “belief that the white slave trade is a great as well as a monstrous evil … has the support of all the commissioners and individuals who have given the matter examination at once honest and careful.”

65

The anti–white slavery crusade peaked with the passage of the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910, otherwise known as the Mann Act—named after Representative James Robert Mann, the sponsor of the bill that Congress quickly passed with little debate. The president signed it on June 25, 1910. The Mann Act went well beyond an earlier federal law, mostly aimed at Chinese immigrants, restricting the entry of prostitutes. Yet again, Congress used its authority to regulate commerce as the basis for expanding federal police powers.

Although the frenzy that created the Mann Act was specifically about stopping white slavery, the language of the law was far more sweeping, vague, and open-ended. The law penalized “any person who … knowingly transport[s] … in interstate or foreign commerce … any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose, or with the intent and purpose to induce, entice, or compel such woman or girl to become a prostitute or to give herself up to debauchery, or to engage in any other immoral practice.…” Those last six words opened the door for federal authorities to police all sorts of other perceived vices. In the next years and decades the Mann Act would be so broadly interpreted that most arrests had little or nothing to do with anything resembling white slavery.

66

The task of enforcing the Mann Act was handed to the Bureau of Investigation, a small upstart government agency with limited jurisdiction. The bureau seized the opportunity to expand its mandate and increase its visibility. Previously confined mostly to Washington, it opened a field office in Baltimore, significantly increased manpower, and deployed agents to cities across the country. It received a major boost when the attorney general established a specialized division, the Office of the Special Commissioner for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic. The Mann Act gave the bureau the kind of feel-good, high-profile, righteous mission through which it could generate public and political support and make a name for itself; later, this included changing its name to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Historians credit the Mann Act for giving the FBI its early boost.

67

The notion that there was a vast, sophisticated, foreign-inspired white slave trade turned out to be overblown, to say the least. Many prostitutes, often immigrants, were certainly exploited and abused. Some were no doubt coerced. But the complex social realities involved many more shades of gray than the black-and-white picture of victims and victimizers painted by politicians, popular publications, and antivice groups. And historians have certainly found no evidence of a global criminal syndicate supplying the country’s brothels. Even the

New York Times

, which had backed the anti-white slavery crusade at its peak in 1909 and 1910, editorialized in July 1914 that “sensational magazine articles had created a belief in the existence of a great interstate ‘white slave’ trust. No such trust exists, nor is there any organized white slave industry anywhere.” In 1916 it described the “myth of an international and interstate ‘syndicate’ trafficking in women” as little more than “a figment of imaginative fly-gobblers.”

68

But even an illicit flesh trade that turned out to be more myth than reality had profound and long-lasting effects. The moral panic surrounding it was relatively short-lived, but it left an enduring legacy of greatly expanded federal policing powers. As James Morone puts it, “In the uproar” over the white slave trade, “policy makers laid down the institutional foundations for federal crime-fighting.”

69

MUCH OF THE MORAL

crusading of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century—whether against smuggled smut, contraband

condoms, or sex trafficking—targeted immigrants as much as these particular illicit trades. So, as we’ll see in the next chapter, it should be no surprise that the federal government also got into the business of immigration control for the first time during this period, stimulating both the business of migrant smuggling and the rise of a national immigration law enforcement apparatus.

12

Coming to America Through the Back Door

AMERICA IS OFTEN CALLED

a “nation of immigrants,” highlighting a long tradition of an open and welcoming front door. But this tells only part of the story. The front door has never been fully open, and became increasingly regulated at the national level in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

1

Consequently, less welcome immigrants developed alternate routes and methods of entry through the back door. They either deceived authorities at official ports of entry or evaded authorities by clandestinely crossing the country’s vast land borders—smuggling themselves in or hiring the services of professional smugglers.

This chapter tells the story of this back door and how it was created, used, policed, and transformed over time. Considering the current policy preoccupation with illegal Mexican immigrants, it is especially striking that the early part of our story has so little to do with Mexicans. Indeed, Americans illegally migrated

to

Mexico long before Mexicans illegally migrated to the United States, moreover, the first illegal immigrants crossing the border from Mexico viewed by U.S. authorities as a problem were actually Chinese.

The influx of foreigners, both legal and illegal, changed the face of America. At the same time, enforcing increasingly restrictive entry laws and cracking down on human smuggling gave birth to a national immigration-control apparatus. Federal responsibility for regulating

the nation’s borders, traditionally focused almost entirely on the flow of goods, was now extended to also include the flow of people. Illegal entrants were numerically far less significant than their legal counterparts, but the political and bureaucratic scramble to keep them out transformed the policing profile of the federal government.