Socrates (14 page)

Authors: C. C. W. Taylor Christopher;taylor

Medieval and Modern Philosophy

The Christianization of Socrates so strikingly expressed by Justin was not the beginning of a continuous tradition. Though Augustine was influenced by Plato to the extent of speculating that he might have known the Old Testament scriptures, he does not follow Justin in claiming Socrates for Christianity. While some Christian writers praise Socrates as a good man unjustly put to death, most of those who mention him refer with disapproval to his ‘idolatry’, citing his divine sign (interpreted by some, including Tertullian, as communications from a demon), his sacrifice to Asclepius, and his oaths ‘By the dog’,

etc.

To the extent that the Platonic tradition retained its vitality in the early medieval period it concentrated on later Platonic works, especially

Timaeus

, in which the personality of Socrates plays an insignificant role, and from the twelfth century onwards the influence of Plato was largely eclipsed in the West by that of Aristotle. The major medieval philosophers show little or no interest in Socrates, and it is not until the revival of Platonism in the late fifteenth century that any significant interest in him re-emerges. As part of the neo-Platonist programme of interpreting Platonism as an allegorical expression of Christian truth we find the Florentine Marsilio Ficino drawing detailed parallels between the trials and deaths of Socrates and Jesus, and this tradition was continued by Erasmus (one of whose dialogues contains the expression ‘Saint Socrates, pray for us’) in a comparison between Christ in the garden of Gethsemane and Socrates in his condemned cell. (The tradition was continued in subsequent centuries, by (among others) Diderot and Rousseau in the eighteenth and various writers in the nineteenth, all of them adjusting the parallelism to fit their particular religious preconceptions.) As in the ancient world, the figure of Socrates lent itself to appropriation by competing ideologies. For Montaigne in the sixteenth century Socrates was not a Christ-figure but a paradigm of natural virtue and wisdom, and the supernatural elements in the ancient portrayal, particularly the divine sign, were to be explained in naturalistic terms; the sign was perhaps a faculty of instinctive, unreasoned decision, facilitated by his settled habits of wisdom and virtue. The growth of a rationalizing approach to religion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which rejected revelation and the fanaticism consequent on disputes about its interpretation, allowed Socrates to be seen as a martyr for rational religion, who had met his death at the hands of fanatics. In this vein Voltaire wrote a play on the death of Socrates, and the Deist John Toland composed a liturgy for worship in a ‘Socratic Sodality’, including a litany in which, following the example of Erasmus, the name of Socrates was invoked.

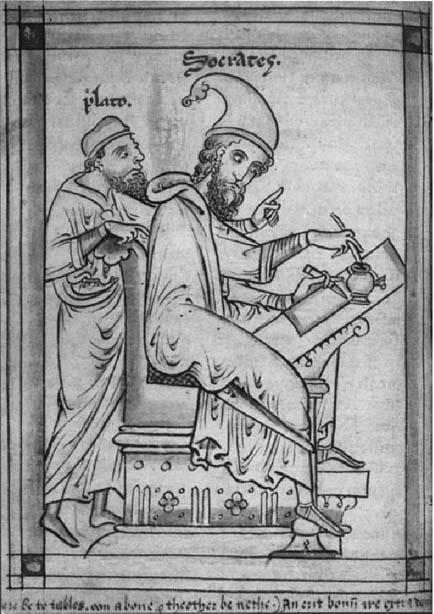

9. Frontispiece drawn by Matthew Paris of St Albans (

d

. 1259) for a fortune-telling tract,

The Prognostics of Socrates the King

. The pop-eyed appearance of the figure named ‘Plato’ and the fact that ‘Socrates’ is writing to ‘Plato’s’ dictation suggests that the names have been transposed. The image appears on a postcard, referred to in the title of Jacques Derrida’s work

La Carte Postale

.

As in the ancient world, there were dissenting voices. Some writers were critical of Socrates’ morals, citing his homosexual tendencies and his neglect of his wife and children. For some, including Voltaire, the divine sign manifested a regrettable streak of superstition. The eighteenth century saw the appearance of the first modern works reviving the claim that the charges against Socrates were political and defending his condemnation on the basis of his hostility to Athenian democracy and his associations with Critias and Alcibiades. (That line

of interpretation continues up to the present, one example being I. F. Stone’s widely read

The Trial of Socrates

.) And some writers of orthodox Christian views repudiated the parallels between Socrates and Jesus, alleging, in addition to the charges of superstition and immorality already mentioned, that Socrates had in effect committed suicide.

The pattern of appropriation to an alien culture has parallels in the treatment of Socrates in medieval Arabic literature. Apart from Plato and Aristotle, he is the philosopher most frequently referred to by Arabic writers, and the interest in him extended beyond philosophers to poets, theologians, mystics, and other scholars. This interest was not founded on extensive knowledge of the relevant Greek texts. While works dealing with Socrates’ death, notably Plato’s

Phaedo

and

Crito

, were clearly well known, there is little evidence of wider knowledge of the Platonic dialogues, and none of knowledge of other Socratic literature. There was, however, an extensive tradition of anecdotes recording sayings of Socrates, of the kind recorded in Diogenes Laertius and other biographical and moralizing writers. This tradition represents Socrates as a sage, one of the ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’ (i.e. sages), a moral paragon, an exemplar of all the virtues, and a fount of wisdom on every topic, including man, the world, time, and, above all, God. He is consistently presented as maintaining an elaborate monotheistic theology, neo-Platonist in its details, and his condemnation and death are attributed to his upholding faith in the one true God against the errors of idolators. This allows him to be seen as a forerunner of Islamic sages (as he was seen in the West as a proto-Christian), and to be described in terms which assimilate him to figures venerated in Islam, including Abraham, Jesus, and even the Prophet himself. Some writings represent him as an ascetic, and it is clear that he is conflated with the Cynics, above all with Diogenes, even to the extent of living in a tub and telling Alexander the Great to step out of the light when he was sunbathing. In other writings he is the father of alchemy, in others again a pioneer in logic, mathematics, and physics.

Again, as in the West, the generally honorific perception of Socrates was challenged on religious grounds by some orthodox believers (such as the eleventh/twelfth-century theologian al-Ghazali), who represented him as a father of heresies, a threat to Islam, and even as an atheist.

9

The tradition of adapting the figure of Socrates to fit the general preconceptions of the writer is discernible in his treatment by three major philosophers of the nineteenth century, Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche. In his

Lectures on the History of Philosophy

, first delivered in 1805–6, Hegel sees the condemnation of Socrates as a tragic clash between two moral standpoints, each of which is justified, and thereby a necessary stage in the dialectical process by which the world-spirit realizes itself in its fullest development. Before Socrates the Athenians had spontaneously and unreflectively followed the dictates of objective morality (

Sittlichkeit

). By critically examining people’s moral beliefs Socrates turns morality into something individual and reflective (

Moralität

); it is a requirement of this new morality that its principles stand the test of critical reflection on the part of the individual. Yet, since Socrates was unable to give any determinate account of the good, the effect of this critical reflection is merely to undermine the authority of

Sittlichkeit

. Critical reflection reveals that the exceptionless moral laws which

Sittlichkeit

had proclaimed have exceptions in fact, but the lack of a determinate criterion leaves the individual with no way of determining what is right in particular cases other than inward illumination or conscience, which in Socrates’ case takes the form of his divine sign.

Socrates’ appeal to his conscience is thus an appeal to an authority higher than that of the collective moral sense of the people, but that is an appeal which the people cannot allow:

The spirit of this people in itself, its constitution, its whole life, rested, however, on a moral ground, on religion, and could not exist without

this absolutely secure basis. Thus because Socrates makes the truth rest on the judgement of inward consciousness, he enters upon a struggle with the Athenian people as to what is right and true. His accusation was therefore just.

(i. 426)

10

The clash between individual conscience and the state was therefore inevitable, in that both necessarily claim supreme moral authority. It is also tragic, in that both sides are right:

In what is truly tragic there must be valid moral powers on both the sides which come into collision; this was so with Socrates. The one power is the divine right, the natural morality whose laws are identical with the will which dwells therein as in its own essence, freely and nobly; we may call it abstractly objective freedom. The other principle, on the contrary, is the right, as really divine, of consciousness or of subjective freedom: this is the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil,

i.e.

of self-creative reason; and it is the universal principle for all successive times. It is these two principles which we see coming into opposition in the life and philosophy of Socrates.

(i. 446–7)

The situation is tragic in that both the collective morality of the people and the individual conscience make demands on the individual which are justified and ineluctable, but conflicting: the only resolution is the development of humanity to a stage in which these demands necessarily coincide. The individual nonconformist such as Socrates is defeated, but that defeat leads to the triumph of what that ‘false individuality’ imperfectly represented, the critical activity of the world-spirit:

The false form of individuality is taken away, and that, indeed, in a violent way, by punishment, but the principle itself will penetrate later, if in another form, and elevate itself into a form of the world-spirit. This

universal mode in which the principle comes forth and permeates the present is the true one; what was wrong was the fact that the principle came forth as the peculiar possession of one individual.

(i. 444)

It appears, then, that the condemnation of Socrates arises from the clash between the legitimate demands of collective (

Sittlichkeit

) and individual morality (

Moralität

), which in turn reflects a stage in human development in which the collective and the individual are separate and therefore potentially conflicting. This stage is to be superseded by a higher stage of development in which the individual and the collective are somehow identified, not by the subordination of one to the other, nor by the merging of the individual in the collective, but by the development of a higher form of individuality in which individuality is constituted by its role in the collective.

Kierkegaard discusses Socrates extensively in one of his earliest works,

The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates

. This was his MA thesis, submitted to the University of Copenhagen in 1841, shortly before the major crisis of his life, his breaking off his engagement to Regine Olsen. (The examiners’ reports are preserved in the university records, giving an amusing picture of the problems of the academic mind confronted with wayward talent.) His treatment of Socrates is Hegelian: for him as for Hegel Socrates stands at a turning-point in world history, in which the world-spirit advances to a higher stage of development, and for him too that breakthrough demands the sacrifice of the individual. ‘An individual may be world-historically justified and yet unauthorized. Insofar as he is the latter he must become a sacrifice; insofar as he is the former he must prevail, that is, he must prevail by becoming a sacrifice’ (260).

11

For Kierkegaard as for Hegel the role of Socrates is to lead Greek morality to a higher stage of development; what is original in his treatment is his identification of irony as the means by which this transformation of morality was to be effected. Classical Hellenism had outlived itself, but before a new principle could

appear all the false preconceptions of outmoded morality had to be cleared away. That was Socrates’ role, and irony was the weapon which he employed:

[I]rony is the glaive, the two-edged sword, that he swung like an avenging angel over Greece . . . [I]rony is the very incitement of subjectivity, and in Socrates this is truly a world-historical passion. In Socrates one process ends and with him a new one begins. He is the last classical figure, but he consumes this sterling quality and natural fullness of his in the divine service by which he destroys classicism.

(211–12)

By irony Kierkegaard does not mean pretended ignorance or a pose of deference to others. ‘Irony’ is given a technical sense, taken over from Hegel, of ‘infinite, absolute negativity’. What this amounts to is the supersession of the lower stage in a dialectical process in favour of the higher. Kierkegaard gives the example of the supersession of Judaism by Christianity, in which John the Baptist has an ‘ironical’ role comparable with that of Socrates: ‘[H]e [i.e. John] let Judaism continue to exist and at the same time developed the seeds of its own downfall within it’ (268). But there was a crucial difference between Socrates and John, in that the latter lacked consciousness of his irony: