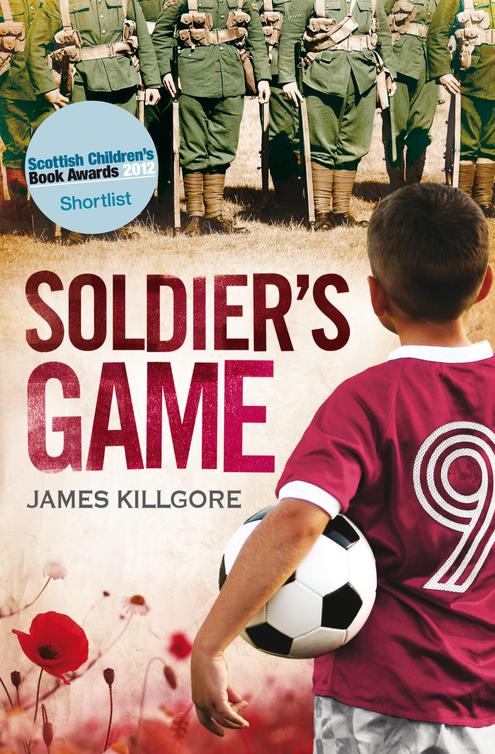

Soldier's Game

Authors: James Killgore

For Emily and Max

The referee blew the final whistle. It was another humiliating defeat for Bruntsfield Primary. Ross joined the line-up to shake hands with the opposing P7 boys from South Morningside. Each player muttered the obligatory “good game” but everyone knew it had been nothing but a joke. Ross couldn’t bear to look in their eyes.

Barry the coach called them into a post-match huddle.

“Okay guys. Good effort,” he said.

“Five-nil?” whined Carl Nelson.

“Yes… well,” Barry replied. “Only one goal in the second half.”

“Because we switched keepers,” said Carl.

Ross looked up at Ying whose face burned red. It wasn’t just his fault for letting in those goals. South Morningside had run circles around them all.

“Just need to work a bit more on basic skills,” said

Barry.

“Like touching the ball,” muttered Carl.

“Why don’t you give it a rest!” Ross snapped.

“Yes. That’s not helpful,” Barry added quietly.

Barry never raised his voice – unlike the other coaches at Bruntsfield. Even Miss Frew shouted more at the P6 girls. He was always calm, always upbeat. Nothing ever seemed to dampen his enthusiasm. It had been that way from the very first Saturday morning practice session back in P2 – all of them chasing a ball around the pitch like a flock of pigeons. Somehow, barely, he had always managed to keep the team in order and even to win a few matches. Lately though there had been some talk about Barry’s methods among the other parents. This was the fourth straight defeat that season.

His dress sense didn’t help much either. Most coaches wore tracksuits but Barry always turned up for training in a baggy wool jacket and trousers with a brown fedora hat. On match days he wore old silk ties and carried the club kit in a battered leather suitcase.

“The guy has never been a winner,” Ross had overheard Bob Nelson say that morning. Bob was Carl’s dad and he turned up every Saturday morning

to holler from the sidelines.

“Pass the ball!”

“Mark up!”

“Tackle!”

“For God’s sake – it’s football, not ballet class!”

Never once did he offer to help Barry with the coaching. Bob was an executive at Standard Life and far too busy. But that didn’t stop him being a critic.

Earlier that morning in the first half Ying had managed to catch a high ball just in front of the goal. He spun quickly and floated it back over the pitch towards Ross at left midfield.

“Down the wing, down the wing,” Bob bellowed.

Ross took the pass off his right heel and drove the ball hard down the line, racing a defender in pursuit. What happened then was unclear. Somehow his feet just seemed to tangle underneath, and the next thing Ross knew he was sliding face first across the muddy pitch. His chin came to rest just at the feet of Bob Nelson and a couple of the other dads.

“Is he a left footer?” one asked.

“Yeah,” Bob replied. “Both of them.”

Ross could still hear the laughter in his head as he walked out of Harrison Park and over the Union Canal. It wasn’t the first time that season he’d tripped

on thin air. He was the tallest and fastest on the team but sometimes his legs just seemed to go each their own way. Just thinking about it made his ears burn with shame.

Ross turned the corner and headed up Polwarth Terrace towards his grandmother’s house. He always went to Pat’s after football on Saturday mornings, as there was no one around to look after him at his own house. Mr Anderson left early for his office at the university for some “peace and quiet without any students around”. Mrs Anderson drove Ross’s younger sister Rachel to a dance studio across town in Portobello. Only his teenage sister Kath would be in the house and she slept until noon.

Now that Ross was nearly twelve he could have let himself into the house. But going to Pat’s had become routine and he enjoyed visiting her. Sometimes it seemed she was the only one in the family who really listened to him.

Pat lived in an old stone semi that backed onto the canal. You could stand at her kitchen window and watch the long narrow boats sail past the bottom of the garden.

The front door into the porch was open and Ross poked his head inside and shouted, “It’s me!”

“In the kitchen,” Pat called in reply. “Milk’s on the boil.”

Every Saturday Pat had hot chocolate waiting for him – the best Ross had ever tasted. She bought the powder from a special shop in Bruntsfield. It came all the way from Bolivia and was eighty per cent real cocoa, and the mug was always piping hot and topped with miniature marshmallows floating in a half-melted froth.

Ross sat on the front step and pulled off his muddy boots and socks, along with his shin guards. The cool tiles of the porch floor felt nice under his bare feet. He padded down the hall to the kitchen.

Pat stood at the stove pouring out hot milk from a saucepan – a tall thin lady dressed in baggy dungarees and an old paint-spattered Icelandic jumper. She wore her white hair cut short like a boy’s and her eyes were blue as a winter sky. In her later years she’d taken up painting and sculpture and sometimes had exhibitions in a gallery down on Dundas Street.

Pat carried the two steaming mugs over to the kitchen table.

“So how did the match go?”

“Disaster,” Ross replied.

“What was the score?” she asked.

“You don’t want to know,” he said. “Liam, our sweeper, was off sick today and nobody played well.”

Ross then told her about the trip-up and Bob Nelson’s “two left feet” comment.

“Forget it,” said Pat. “That’s just a cheap shot from someone who should know better.”

“But I am clumsy,” he muttered.

Pat cocked an eyebrow.

“Nonsense. You’re just growing. It’s only a matter of finding your feet.”

Ross slumped in his chair.

“But you’re my grandmother. They pay you to say that.”

She gave him a sudden sharp look.

“Have I ever lied to you about anything?”

Ross shook his head.

It was true. Pat never spared his feelings. Should Ross draw a picture that she didn’t like she’d say so and tell him why. Or if he fumbled through a tune on the piano she’d say “needs more practice”. Not like other adults who’d gush over any old rubbish.

Pat stood up from the table.

“Finish that mug. There’s something I want to show you.”

“Now?” Ross replied.

“Yes. Come on. Drink up,” she ordered.

“What is it?” Ross asked.

“That’d be telling,” she replied. “But I hope you have a head for heights.”

Pat rooted through a kitchen drawer for a key. Ross followed her out the back to the garage where she opened a padlock on the door. Along one wall of the junk-filled space hung a long wooden stepladder. Together they lifted it off the metal hooks and carried it back through the kitchen and up the stairway. Pat then pointed to the ceiling above the upper landing. High overhead was a small white wooden hatch.

“Not a word about this to your father,” she said. “Maybe you should hold the ladder for me first.”

Together they positioned the stepladder under the hatch and Pat climbed slowly up the rungs to the ceiling. She reached up and slid the hatch aside. With effort she managed to pull herself up into the opening. A light appeared first and then Pat’s head.

“Your turn,” she said. “But slow and careful.”

Ross clambered up the rungs without looking down. Pat reached from the opening to give him a hand up. Climbing off the top step and up into the broad ceiling gave Ross a dizzy feeling and he realised it wouldn’t be so easy getting back down.

The attic ran the length of the house – a dim, dusty space with a rough ply-board floor nailed over the joists. A single bare light bulb hung just above the hatch casting a dull glow over stacks of cardboard boxes, clothes racks, a dressing mirror half covered by a sheet, an antique set of golf clubs, an old mahogany gramophone. Dead wasps littered every surface and cobwebs billowed in the draft.

Pat had a look around.

“Do you know, I don’t think I’ve been up here once since your grandfather died.”

Ross picked up a heavy wooden tennis racket out of an old umbrella stand. “Where did all this stuff come from?” he asked.

“Oh, it’s been accumulating for years – my family, John’s family,” she replied. “Plenty of hidden treasure up here.”

“Treasure?” Ross exclaimed.

“Don’t get your hopes up,” said Pat. “No gold or jewels – nothing as common as that.”

A faint light shone from a stone vent at the far end of the attic. Pat headed towards it, pushing aside the cobwebs.

“Back here if memory serves,” she said.

Ross followed, ducking his head to avoid the roof

beams. Tucked in a corner against a stone chimney stood a set of rusted metal shelves stuffed with ancient box files and old magazines bound in twine. On the bottom shelf sat a larger object covered with a dustsheet.

Ross peered over her shoulder as Pat reached down to pull away the sheet. Beneath it was a wooden chest with a dull brass catch.

“I thought you were kidding about treasure,” said Ross. “What’s in there?”

Pat smiled and slid the box off the shelf onto the floor.

“Why don’t we take it down to the kitchen for a better look?”

Getting the box down from the attic proved tricky. It wasn’t so much heavy as awkward in shape. Ross lowered himself first through the ceiling hatch, feeling for the top of the ladder with his foot.

“Good. Now get your balance,” said Pat.

He climbed down a couple of rungs and steadied himself before reaching back up for the box. But the ladder began to wobble.

“Is this a good idea?” he asked.

Pat frowned.

“Maybe not.”

She pulled the box back into the attic.

“Go on down,” she said. “We’ll try something else.”

Ross climbed to the bottom. He could hear thumps and bumps as Pat rummaged above. After a while she called down, “Move the ladder.”

“What?”

“Move it aside.”

Ross did as he was told and a minute later the box appeared again in the hatchway bound in a rope sling that Pat had improvised from some washing line. It spun slowly down from the ceiling into Ross’s arms.

“Got it!” he shouted.

“Excellent,” she called from above. “Now, if someone could just lower me.”

Ross pushed the ladder back into place and held it steady as Pat eased herself through the hatch and climbed slowly down to the landing.

“Not a broken bone between us,” she puffed.

Ross carried the box downstairs to the kitchen and laid it on the breakfast table. Here in the bright sunlight he could see it was neatly crafted in pine, the wood stained dark maroon under a heavy coat of varnish. Just below the brass catch were the initials HM, hand-painted in gold with elaborate intertwining script.

Ross was desperate to open the box but Pat seemed oddly hesitant. She ran her hand lightly over the lid. After a few moments Ross looked up and found that she was crying.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“Nothing. Just me being silly.”

She pulled a tissue from the sleeve of her jumper.

“Do you know who owned this box?”

Ross pointed to the initials. “HM?”

Pat smiled and shook her head.

“It belonged to my father, Jack Jordan. He made it himself when he was fifteen years old.”

“Your father made this?” asked Ross.

“Yes – in the craft workshop at Boroughmuir High School,” Pat replied. “Have a look.”

She turned the box around and pointed to an inscription carved neatly in the lower back corner: JJ 1911

Pat brushed her fingers over the marks and then turned the front of the box back towards Ross.

“Go on then. Open it,” she said.

Ross reached out to the catch and tried to imagine what he might find inside. Not gold but maybe some valuable family heirloom like on Antiques Roadshow – a collection of old coins or an ivory chess set or letters by somebody famous.

He flicked the small brass hook free of its loop and lifted the lid. Inside the box, nestled among crumpled yellow newspapers, lay a pair of leather football boots. Pat smiled at the look of disappointment on his face.

“Not what you expected?”

“Not exactly,” Ross muttered.

“Well some things are worth more than they look,” she said.

“But it’s just a pair of old boots,” he replied.

Pat sighed.

“Do you know that the year Jack Jordan made this box he played centre forward for both his school and Edinburgh’s top boys’ football club. But his one ambition then was to someday take to the pitch at Tynecastle for Heart of Midlothian – HM. Three years later that’s just what he did.”

Ross was dumbstruck.

“Your father played for Hearts?”

“Before the Great War broke out,” she replied. “Only for one season…”

But Ross was too excited to listen.

“I remember you told me that he liked football but you never said he played professionally!”

Pat had once shown Ross a black and white portrait of her father. It was on the mantelpiece in her front room. A thin old man dressed in a grey three-piece suit and tie sat in a leather armchair, his walking stick clasped between his knees.

“That’s your great-grandfather,” she’d said, giving it to Ross to hold as she dusted. “He was just as

Hearts mad as you: a club member at Tynecastle for over thirty years. He rarely missed a game.”

Ross remembered the face in the picture – pale and gaunt. Pat said that he had died a long time ago. Ross couldn’t believe it had never occurred to her to mention that her father had played for his favourite team. He had a million questions.

“Were these his boots at Hearts? What position did he play? Was he a defender, midfielder or a striker? Did he score any goals?”

Pat smiled.

“Let’s see what else we can find.”

She took out the boots and laid them gently on the table. Underneath the newspaper was a layer of tissue covering a neatly folded strip along with white shorts and thick wool socks. Pat carefully lifted the jersey and held it up to the light – bright maroon with a white collar.

Beneath the clothes was an A4 envelope as well as a small cardboard jewellery box. Pat took out the envelope and spread the contents onto the table. Among the heap of faded football programmes and newspaper clippings was a photograph of a young Jack Jordan dressed in the same kit that now lay on the table before them – a thin but fit young man

gazing into the camera with a cheeky, lopsided grin.

Pat held out the photograph and stared across the table at Ross.

“I can definitely see a resemblance,” she said.

“Let me look.”

Gazing down at the old print Ross could indeed see himself reflected in Jack’s face: around the eyes, in the angle of his cheek. It was a little spooky. He handed the photo back to Pat and reached for the jewellery box.

“What’s in here?”

Ross opened the lid. Inside, wrapped in cotton wool, was something curious – a small silver badge. It had a circular border and was centred with a crown and interlocking initials in elaborate script. A motto around the outside read: “For King and Empire – Services Rendered”.

“What’s this doing in a box of football kit?” Ross asked.

“Odd, isn’t it,” Pat replied. “My father used to keep it in his top dresser drawer but he must have packed it in the box before he died.”

Just then Ross heard the toot of a car horn out in front of the house.

“That’s your mother now. Let’s get these things

back in the box.”

“Please. Just a couple minutes more,” said Ross.

“No. I don’t want to keep her waiting.”

Pat packed everything away and Ross gathered his kit. She followed him with the box out into the front hall. Just as he turned to the door she said, “Wait. I want you to have this.”

“Me?” said Ross. “But why?”

“Because I want you to keep it safe,” she replied.

“Safe? I don’t understand.”

Pat sighed.

“Safe because I won’t be around forever to look after it.”

Ross felt a flash of panic.

“Yes you will.”

“No I won’t, but never mind that now. What’s important is that I’m trusting you to look after it. Your father certainly has no interest.”

Tears welled in her eyes as she placed the box in Ross’s arms. The car horn sounded again.

“Promise me you’ll take care of these things. They really are beyond value.”

Ross nodded, though he wasn’t exactly sure what she meant by that. Pat opened the door for him.

“So will I see you next Saturday?”

“Same as always,” he replied.

***

Out in the car his mother had the radio on loud. Ross climbed in the back seat next to his little sister Rachel, who was still in her leotard from dance class.

“What’s in the box?” she asked.

“Just some stuff from Gran’s attic – old football kit.”

“Sounds smelly,” said his mother.

Rachel laughed and stuck her tongue out at Ross. He resisted the temptation to smack her and instead stared out at the passing houses. To think that his great-grandfather had played at Tynecastle all those years ago.

Ross had been to about a dozen Hearts home matches. A friend of his mother from work – Simon – had two season tickets and sometimes invited Ross along. Otherwise he might never have been to a match. Certainly his father wouldn’t take him.

Frank Anderson thought football an absurd pursuit. It was one of his favourite dinnertime rants. “Grown men paid millions of pounds for kicking a ball about,” he’d huff. “It’s just a game. There are

countries in Africa worth less than Ronaldo.”

Pat said that even as a boy Frank disliked team sports, not being much of an athlete. Ross couldn’t recall ever seeing his father break a sweat much less run and kick a ball, but he had no objection to his son playing football. “It’s your free time to waste,” he’d say. “Just don’t expect me to waste mine watching.”

On Hearts match days Simon would turn up at the house early for a bacon roll and a cup of tea. He was a big man and completely bald, which made him look a bit like a nightclub bouncer, though he was nothing of the sort. Few people could be more easygoing and friendly than Simon.

After lunch they would set off from the house and down Polwarth Terrace. Here they’d meet the first trickle of other fans bound for the match. By Harrison Road the trickle grew to a throng with people emerging from every side street. Reaching Gorgie the throng swelled into a crowd that choked the pavements as supporters poured from the pubs, having eaten their pies and downed their pints. Ahead, Tynecastle stadium loomed over the tenements like a citadel. On to the turnstiles they’d be swept in a tide of maroon hats and scarves.

But the moment Ross loved most was when he

emerged from the dim tunnel through the stand into the bright open arena. Players warming up on the pitch below, music blaring, 18,000 fans in a roar of conversation, the air of hope, expectation – it took his breath away every time. It was like the feeling you get on suddenly coming to the top of a high hill, or the moment on holiday you first reach the beach and find a vast blue ocean spread out at your feet.