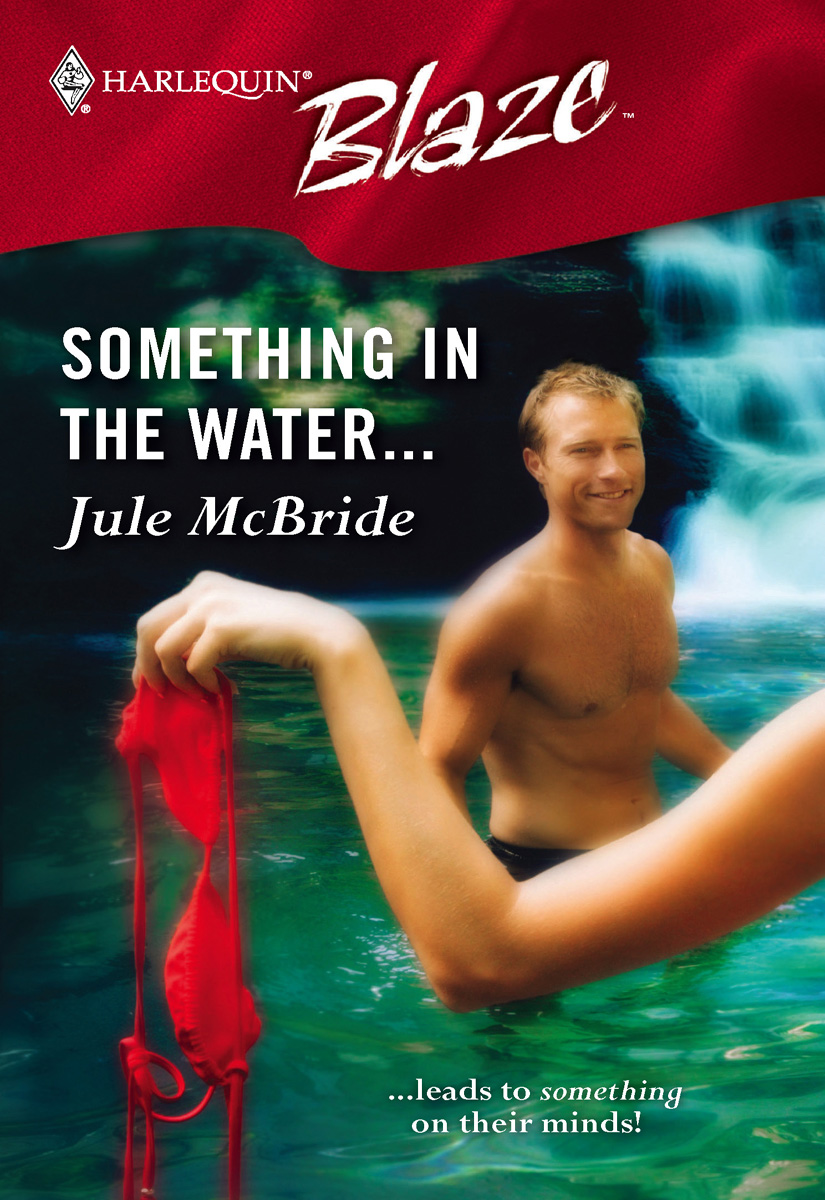

Something in the Water...

Read Something in the Water... Online

Authors: Jule McBride

“If I get love-struck I may never go home.” Rex rose, pulling her up with him.

“Why do I feel like a guinea pig?” she asked.

“Because I’m a born scientist. I need to explore every inch of my subjects.” He smoothed her dress down, feeling the warmth of her skin beneath the soft curve of her belly. “If Romeo’s in the water,” he promised, nuzzling his face against her neck as they began to walk toward the spring, “the outcome could be very dangerous.”

“That’s my hope,” Ariel said. “And because you’ve already gathered all your samples and the bug only stays in the bloodstream a week, things could work out perfectly….”

Rex knew he was acting uncharacteristically, but surely that was only because she was so gorgeous.

“A week of sexual bliss,” he murmured.

Sexual bliss indeed…

Dear Reader,

I hope you’re ready for a hot, wild, sexy read!

West Virginia, with its lush mountains and deep river valleys, seemed just the place to set a humorous story with a taste of mystery. At first, sexy Rex Houston, a doctor from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, isn’t that thrilled about taking a trip to the tiny town of Bliss, but everything changes when he meets Ariel!

Enjoy their love story!

Jule McBride

HARLEQUIN BLAZE

67—THE SEX FILES

91—ALL TUCKED IN…

Jule McBride

Bliss, West Virginia

“T

ELL US ABOUT

Matilda Teasdale again, Pappy,” urged sixteen-year-old Jeb Pass. He blew blond bangs from brown eyes, then glanced at his gangly dark-haired buddy, Marsh, who was seated next to him on a fallen tree limb, staring across the dying campfire at Jeb’s grandpa. Pappy tugged his beard and petted his gray mutt, Hammerhead; the dog was curled up, his tail twitching in tandem with a red bandana around his neck, as if he were chasing rabbits in his dreams.

“Seems to me,” Pappy mused, “by now you ought to know all the stories about Matilda by heart. You boys were born and bred in Bliss, and with Jeb being a history buff and all, too.”

“C’mon, Pappy,” Jeb insisted. “Was she really a witch?”

“Or just some weird lady from England?” Marsh squinted.

“I bet she

was

a witch,” said Jeb. “I even bet they tried to burn her at the stake, the way everybody said. That’s why she came to America in the first place. Huh, Pappy?”

Pappy considered, surveying the star-studded night sky. “I reckon no one really knows, seeing as Matilda

came to Bliss in the 1700s. She’d brought enough money to the one-block mining town to build the house overlooking the spring. People claimed she’d come with only a Native American guide to help carry two worn leather trunks. It was said he was a Cherokee medicine man who’d offered Matilda safe passage across the mountains in exchange for her secret blends of curative teas. Some said she wasn’t a witch at all, but that she came to Bliss because her teas could only reach full potency when blended with the world’s finest water.” Pappy smiled. “And that means from Spice Spring.”

“But how’d she hear about the spring if she was living in England?” Marsh asked.

Pappy shrugged. “Your guess is as good as mine, kid.”

Suddenly shuddering, Jeb stared across the spring, settling his gaze where the surface glimmered under moonlight. When his eyes found the opposite shore, they floated up the stone steps carved into the mountainside and stopped at the top of the hill, on the old Victorian house that local kids had nicknamed Teasdale’s Terror.

The women who lived there now each went by the last name of Anderson, not Teasdale, but they were related to Matilda. Anderson was a name that one of the women—no one really knew which one—had gotten by marriage. How summer visitors managed to stay in the huge house, now a bed-and-breakfast, Jeb would never know. The place looked about as homey as Dracula’s castle. He wondered if Michelle McNulty had really bought magical teas there last summer, the way she’d claimed. Every year, Michelle came from Charleston with her family and rented a cabin on the water, but this year she seemed…well, grown up.

It wasn’t just that she’d gotten a job waitressing at Jack’s on Bliss Run Road, then had started moonlighting by helping to construct booths for the upcoming Harvest Festival, taking place at the end of the week. There were other changes, like how she’d filled out under her T-shirts more than most soon-to-be high-school freshmen. When she fixed Jeb a pie or soda, he could see her breasts sway under cotton and even make out her nipples pointing out, thanks to the air-conditioning Jack blasted in the diner.

This summer, Michelle had quit holding Jeb’s gaze, as if she’d realized her looks were affecting him and couldn’t handle it. Not that Jeb could offer any advice, but he did have fantasies of sitting beside her in the Bliss theater, the only place in town showing first-run movies. Afterward, he figured he might cup her knee with his hand, then run it ever so slowly upward on her thigh….

“Ah,” murmured Pappy, following Jeb’s gaze, “The Teasdale Terror House.”

“Now, are those witches really related to Matilda?” asked Marsh, speaking of the Andersons—the great-grandmother and two generations of daughters. A fourth Anderson, Ariel Anderson, had flown the coup years ago. “Maybe they really did kill their husbands,” he added darkly. “That’s what some people say.”

“I don’t think they’re witches,” Pappy chided. “When you see them in town, you know as well as I do that they’re always polite.”

“A cover,” assured Jeb.

Pappy chuckled. “They do dress weird.”

“All in black,” added Marsh. “Like someone died.”

“Their husbands.” Jeb nodded with assurance. “The

oldest one’s got to be a hundred years old. They say she still moves like lightning, and uses a broomstick, instead of a cane. None of them ever go to the movies or take vacations.”

Marsh looked vindicated. “And they sell those teas.”

Pappy smiled. “The ladies do own a tearoom, boys.”

“They don’t have friends,” Marsh continued.

“And no one will go up there in the winter,” added Jeb, although he’d done so on a dare once. It had been a snowy night, and when he’d reached the wraparound porch and prepared to ring the doorbell, the wind had picked up, howling in his ears, and he’d wrenched around, staring toward the woods where Marsh and their buddies had sworn they’d wait. He’d seen only evergreens, which he’d figured sheltered everything from ghosts to bobcats.

Just as he’d been about to press the doorbell, Jeb had heard a branch break. Wolves in the woods, he’d thought, then leaves had rustled, and Jeb had realized, someone—or some

thing

—was pushing aside the underbrush, moving toward him, steadily.

That’s when Sam Anderson—Sam was short for Samantha—had swung open the heavy front door so swiftly that it had snapped backward on its groaning hinges; the heavy brass demon-head knocker clanked and wind ruffled a white apron Sam had worn over a long black dress. She was Granny Anderson’s daughter and Ariel’s mother. “What are you doing out there, Jeb Pass? Why, you’d better come in. It’s colder than a witch’s—” Chuckling, she’d cut off her speech and scrutinized him through devilish eyes.

Spinning around, he’d run all the way down witches

mountain, sure that whatever he’d heard chasing him was huge and hairy, with claws that could shred him to pieces. Of course, that had been years ago. Way back in seventh grade.

“In the winter, all they do is read books from the library,” Marsh was saying.

“Giblets is the only one they ever talk to.

Miss Gibbet,

” Jeb corrected. Elsinore Gibbet, the librarian, was well past sixty and as scrawny as a chicken, with extra skin under her chin and a chirpy voice that had inspired local kids to call her Chicken Giblets. Jeb continued, “At the library, she showed me a history book that says weird stuff’s always gone on in Bliss, Pappy. Starting in the 1700s—”

“After Matilda came to town,” Marsh put in.

“They say there started to be periods of time when…”

“Something goes…well, buggy,” Pappy suggested.

Jeb nodded. “And because of it, Miss Gibbet said people used to come from all over the place, just to swim in Spice Spring.”

“From as far away as China,” continued Marsh.

“Especially during summers like this one,” Pappy added. “When the water’s been chilled by a series of cold snaps, then the weather heats up again. And during such a summer, when the sun, moon and stars align just right, they say a dip in Spice Spring can change your life. Especially your love life.”

Jeb thought of Michelle and felt his cheeks warm.

Pappy went on. “At the end of the summer, folks used to come here from bigger towns to bottle the water. And of course, they’d head up the hill, to the Andersons’, for medicinal teas.”

Jeb thought of the mysterious book of tea recipes said to have been handed down by Matilda. According to rumor, the book had a cloth cover and pages so yellow and brittle that it had to be kept in a safe in the witches’ root cellar.

As every kid in Bliss knew, the Anderson women had taken to hiding from the public and wearing black. Except for the youngest one, Ariel. When she’d kissed the witch house and tearoom goodbye and roared out of Bliss on her Harley Davidson motorcycle eleven years ago, she’d been wearing red fishnets, a tight leather miniskirt and a top that had looked more like fancy underwear. Jeb had only been five years old, but it was the sort of moment no one ever forgot.

Later, he’d heard all the hot gossip about the sexy things she’d done with Studs Underwood, years before he’d gotten elected sheriff. Even now, Jeb’s face colored, since some of the local guys could get pretty descriptive when it came to tales of Ariel.

“When the moon’s just right and the stars align,” Marsh began again. “And they make teas with water from Spice Spring…is that when you get cured from whatever’s bothering you?”

“Not so much illnesses,” said Pappy. “But matters of the heart. You know, sadness. Loneliness. That sort of thing. At least, that’s what I always heard. And of course, those women make love potions.” Pappy raised a bony finger. “But don’t you start getting ideas about stealing that book of theirs. Attempts have never been successful.”

“I’d hate to get the widows mad,” admitted Marsh.

“I remember,” Pappy continued, “just a couple years

back, the sheriff got called up to the tearoom. Somebody had taken a hatchet to the root-cellar door, tied a rope around the safe and tried to drag it up the steps.”

“Guess they couldn’t get it open,” Marsh offered.

“I heard about that,” said Jeb. “It took three men to haul it back downstairs.” He followed his grandfather’s gaze over the water. The source of the spring was deeper than Jeb and his buddies could dive, although they’d spent summers trying. Once, Jeb had gotten close enough to feel the heat bubbling from beneath; it was as if a hole had opened onto the earth’s fiery core.

The spring’s source was directly under the mountain on which Terror House was perched. It was as if the spring itself had given rise to the steep, conical, lushly vegetated hill, as well as the house that sat on top, like a dark cherry. It was weird, Jeb thought, how the spring, rather than coal, had become the town’s black gold. That, and the visitors summering there.

“At least the Core Coal Company didn’t wind up strip-mining here,” Jeb said.

Pappy nodded his agreement. “If they’d done that, you wouldn’t see a spot of green left in these hills.”

Jeb had been studying that piece of town lore, so he knew that, in the late seventies, when the economy had been at its worst, the Lyons family had begun to buy land, promising to develop the area as a summer resort. Later, everyone had found that the consortium they’d belonged to was actually planning to strip-mine, which would have left the hills barren. Without vegetation to filter rainwater, the crystal spring would have been destroyed.

Jeb sighed. None of that had happened, thankfully. Eli Saltwell, now a crotchety old recluse pushing ninety,

had uncovered the plot and told everybody in town. So, Bliss had become a summer resort, but one run by locals, not the consortium. It didn’t have the promised fancy hotels, but then, most people felt that was just as well, since out-of-towners came anyway.

In another week, after the Harvest Festival, the summer visitors would be gone, though.

Michelle

would be gone. Jeb’s heart squeezed in a way that was both unwelcome and unfamiliar. He’d give anything to kiss her once. Maybe even slip his hand under her shirt and cup a breast. His throat tightened as he imagined her sweet pink lips parting, asking for more….

Pappy’s voice drew him from the reverie, and before Jeb could concentrate on the words, he was conscious once more of the thick, dark blanket of air around him, and of the red-yellow glow of logs crackling on the fire, not to mention the pup tent and his unrolled sleeping bag. He heard the hoot of an owl, the whine of crickets, and then stared up at the impossibly yellow globe of a full moon hanging in the sky, bisected by the turret.

It was pure magic.

“It really is one of those special years,” Pappy mused. “We’ve had a series of early cold snaps, and now summer’s back in the air. Once—I guess it was way back in 1790—not long after Matilda arrived, they say we had this kind of strange weather. Unpredictable. Cold then hot, with a few electrical storms thrown in for good measure. They say, for about a week, everything in Bliss…”

Jeb and Marsh scooted on the log, as if to get closer to Pappy. “What?” Jeb said.

“Went silent,” Pappy continued. “A woman named Nellie White was supposed to travel to see her mama

over in Buchanan, but never went, as she’d promised. And they say Archibald Evans, the blacksmith, didn’t get out of Bliss to shoe some horses, even though he had an appointment. The local paper—it was only one sheet long in those days—wasn’t delivered the way it was on most Fridays.”

Pappy paused. “They say it happened again, not long after that, too, back in 1806.”

“I heard a train came through. They’d built the tracks by then,” said Marsh. “But it didn’t leave the station for a week, and the conductor would never say why.”

“And in 1865, right?” added Jeb, his voice quickening. “That’s what Gib—uh, Miss Gibbet—told me and Marsh.”

“Yeah,” agreed Marsh. “She said it was during the Civil War. The North was coming one way, and the South was coming another—”

“But both sides laid down their weapons,” continued Jeb.

“And no one knows why,” Pappy finished.

Jeb nodded. “Miss Gibbet said the war picked right back up, though.”

“And then she said that in 1943—” began Marsh.

“When the munitions factory was here—”

“It didn’t deliver orders for guns,” said Jeb. “There was a blackout, too. And no phone service. Planes flew overhead, and pilots said, from the air, the town looked totally dark.”

“Now, if all that was true,” said Pappy with a soft chuckle, “you’d think the U.S. government would get involved. Still, according to statistics, they do say a lot of babies have been conceived during those lost weeks.

In fact, my mama got pregnant with me during the blackout of forty-four, if you must know.”

Jeb said, “No way!”

Pappy crossed a finger over his heart. “So I’m told. There’s no pattern to when the town…well, goes silent. But they do say it happens when the weather’s like this.”

Marsh guffawed. “Wish it would happen week after next, after the Harvest Festival.”

“Fat chance,” Jeb said, trying not to think of the festival, and his last chance to get closer to Michelle. “That’s when school starts.”