Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal (12 page)

Read Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal Online

Authors: Silas House and Jason Howard

They don't have to tell the truth. They may get your lease signed now and have no earthly intention of mining until the price goes up to who knows what, you may not live to see any of that money.

When people do business with the coal company, they're dealing with outlaws. It's like going to Vegas: you go and you think you can beat the house. You can't beat the house. They've got everything all tied up. They're going to make sure you can't beat the house. You can't beat the coal company. It's a big gamble, and they're not going to lose.

And if it's a local company, they have no more morals or sense of responsibility to the community. There's only one thing they're there for, and that is to harvest coal. It doesn't matter what's in their way. It doesn't matter if a cemetery's in their way, it doesn't matter if the homeplace is in their way, it doesn't matter if a hugely valuable forest is in their way. That's garbage, all of that is garbage. You can toss it over the hill. All that matters is getting the coal out and getting the coal out in as cheap a manner as it can possibly be obtained, and that's mountaintop removal. And that's why we've got this thing visited upon us.

One of the awkward things about organizing everyone on Wilson Creek is with the folks who have been approached to sign leases, and I don't really feel at liberty to talk with them a lot. It's like getting into somebody else's business. It's kind of awkward. I realize somewhere along the line that what I'd like to say to them is whatever you do we're still neighbors, we're going to be neighbors a long time after the May Brothers or after the Miller Brothers Coal Company comes through here. We're a community, no matter whatever happens. I would like to say that to some of my neighbors, and I haven't.

I don't believe any neighbors or family have gotten mad at me over speaking out, but they will. When this happens in a community, there's some larger landowners who stand to make some

extra money and the smaller landowners that always get the damage, and what that can do is really tear a community apart. And the sad thing here on Wilson Creek is we're talking families who have lived here for four generations or more and we've all gotten along just fine. We all go to church together, respect each other, and everybody gets along good.

I think it's just tragic that it puts us in a position where all of a sudden people are almost pitted against each other. It's a real tragedy when a community gets torn apart that way. What happens is some people will sell out—I hope not here—or some people sign and let them mine. How can you not have hard feelings when the foundation gets blasted out from under your house and your neighbor has made who knows how much money? It's pretty tense.

When the May Brothers Coal Company representatives started trying to buy leases from people here back before Christmas, one of the ways to try and fight back we came up with was the idea of a “lands unsuitable for mining” petition. As part of that, we wanted to document the biodiversity that's right here on Wilson Creek and maybe find a rare species or two if we were really lucky. Some of these students in botany and agriculture came up from Berea in the early spring, and we went wildflower hunting, and this was the last place I brought them.

One of the students said that she had really wavered about coming because she had to finish a paper and it was due. Oh, this was Easter weekend. God love them, they gave up their Easter weekend to come and hunt for wildflowers, which I thought was incredibly sweet. So anyway, she decided she would come and she realized once she got up to this spot that it was exactly the right thing to do because now she knew; she understood what it's really all about. That made me feel really good. I hope I can do that for a lot of other students, because I think they really understood

this

is what you lose when you blow up a mountain. They went back all ready to join the fight, so I was really pleased with that.

Unfortunately people trust the May Brothers because they're local and they're respected as local people who have made a lot of money. Folks tend to respect people with a lot of money no matter what they did to get it. So that's kind of disturbing, because they can come around and talk to folks and get them to sign their leases even though, apparently, from what we can determine, they're not the ones that are going to do the mining. They want the Miller Brothers to do it, which of course means that what they tell people and what they're promising and what will actually be delivered by the Miller Brothers—it's a completely different company I'm sure—will be two very different things.

I think that we're going in the right direction. We're appealing to people across the state. A great strategy is the Mountain Witness Tours. We had one in August, and I think that's a really powerful thing. Like I was saying, you can't understand what you've lost or what's happening unless you actually see it with your own eyes. It's possible to say, “Okay, they're going to blow the top off of a mountain and they're going to shove all the dirt in the valley,” but the human mind can't conceive of how huge an area that is unless you're just looking right at it and say, “Oh my God, it's everything I can see in a 180-degree direction.” It's impossible to appreciate what a 3,000-acre mine looks like unless you've stood on a mountain and seen it, and when you do your life is never going to be the same.

I think that so many people have been touched or damaged by the coal industry, and yet at the same time they don't see a way necessarily to do anything about it. I've told the folks at work what I'm doing and they say, “That is so great. I'm so glad somebody is standing up to them.”

Stand up with me! That's a harder step to take.

One of the nurses I work with, their foundation was cracked by a mine that was miles away and they've not been offered anything for it, they've not gotten anywhere with getting it fixed. They just sort of do what people do, which is just go on and hope it doesn't cause any serious structural problem. Which it will, of

course. And she said, “I'm so glad you're doing this because it's not right.”

People know it's not right that a coal company can cause damage to the foundation of every house for three miles, but what do you do? And people are, of course, beholden to the coal company for jobs, and when you're talking about somebody's payday, that's a great way to control their use of their civil rights.

One of the ways that coal companies around here will try to get leases from people is to promise a job to a relative or promise to fire a relative. It goes either way. So that's very frustrating because they've got them tied up economically.

This is my home.

I just put everything I've saved in my entire life into this house. I'm here because I want to be here. I could work anywhere. I really could. When you're a nurse you've got your ticket. But my family's here, my whole life is here.

It's not an accident that I play old-time music on the fiddle. Not even old-time music;

Kentucky

old-time music is my particular love. Or that I have chairs in my house that have had their bottoms caned by somebody down the road or a local guy that made my cabinets.

I live here, and I value and I love being in the mountains. This is home in the all-inclusive sense, and I will not be run off of it.

I know for an absolute fact they will never mine my place because they have to have my permission to do it and they're never going to get that. So that I know for a fact. But I know they can make it so uncomfortable and unlivable for you that they can force people out when they start blasting your house and poisoning your dog. It can get real ugly. I know that.

But I also know they can't make me sell. I know that for sure.

I just have no desire to live anyplace else. I want to be here because this is my life. There's just a lot of meaning to me in being here in this place. I've got work that is meaningful and peaceful, I've family nearby that look out for me and I look out for them,

I've got a community that I'm a part of. Where else in this whole country would I ever have that? I'd have to make it all over again, and it would never be equivalent. This is a blessing that I was given just by virtue of the fact where I was born. I'm not going to toss that away. I am certain in my heart that I am where I am supposed to be and doing exactly the work I am supposed to be doing. Why would I let a coal operator change that?

Wilson Creek, Kentucky, October 20, 2007

Union Made

The fight is never about grapes or lettuce. It is always about people.

—Cesar Chavez

I'm sticking to the union

'Til the day I die.

—Woody Guthrie, “Union Maid”

Carl Shoupe is mad as hell. You can't hear it in his voice or even see it in his eyes. The clench of his firm, mountain jaw—his inheritance from his Cherokee grandmother—is the giveaway. As he stands to address the Bank of America shareholder meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina, he chooses his words skillfully, succinctly, ever the true Appalachian diplomat: “I came all the way from Kentucky because I am trying to save my homeland from total destruction caused by mountaintop removal coal mining, which Bank of America is a leading financier of. The southern Appalachian Mountains have some of the most biodiverse forests in the world. Mountaintop removal coal producers, funded by Bank of America, are exploding tops off these mountains and off our culture. This is not just about saving the climate, but also about the survival of our culture for our grandchildren and future generations.”

Some of the shareholders and board members look at each other, brows crinkled in confusion. Many have never heard of mountaintop removal, let alone that their company, their own money, is subsidizing it. Others simply aren't used to such straight talk.

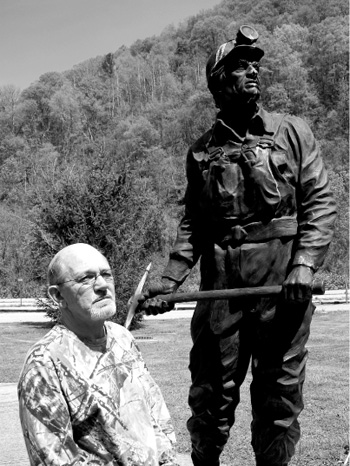

Carl Shoupe at Miners' Memorial Park in Benham, Kentucky. Photo by Silas House.

More anti–mountaintop removal activists who have come from across Appalachia stand up to speak. The face of Ken Lewis, Bank of America's CEO, is as red as a pickled beet. He has been ambushed.

And now

he's

mad as hell.

It is reminiscent of another corporate confrontation nearly forty years ago, when striking miners from Brookside, Kentucky, in Shoupe's native Harlan County, trekked to New York to say their piece at a Duke Power shareholder meeting. Chronicled in the Oscar-winning documentary

Harlan County USA

, it became a turning point in their fight for a living wage.

1

Things are different today in Eastern Kentucky. The union has gone, having ceded its bloodied, hallowed ground to the companies and strip-mining operations. Deep mining is a lost art form; mechanization has long since taken over, replacing respectable underground miners with garish heavy equipment.

But in many ways, it's a place still at war over coal. The tactics of the coal companies remain the same: divide and conquer. On the other side, Shoupe and the grassroots organization he works with, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC), find themselves fighting to bring people together in a broad coalition in the wake of the union's retreat.

“I talk about it daily,” Shoupe says, seated—appropriately—at the Coal Miners' Memorial Park in Benham. “At the grocery, at the speedway, wherever. I had a conversation yesterday morning; a very respected man in the community. A professor. He said, ‘You go, Carl, buddy, you get out there and you keep talking, you're doing a great job.' I said, ‘Why don't you help me out a little bit?' and he said, ‘Ah, buddy, I can't say much; they'd run me off.'”

He pauses long enough to breathe a shaky sigh of frustration. “So see, people know it's bad, that it's destroying our water, our culture, but like everything else, it's about money. People ain't speaking out about it. People are afraid of losing their jobs.”

Shoupe, like so many others involved in this fight, believes

that once again King Coal is using the big lie that is the biggest weapon it has in its pocket—in this case, that mountaintop removal provides jobs instead of replacing them with machines. And they're using it in full force.

Shoupe isn't about to back down from the fight. He responds with his own bombshell: “I'm a third-generation coal miner. If you can't deep mine it, it ain't worth getting out of the mountain in the first place!”

Coming from a family of deep miners, Shoupe has certainly earned the right to make such bold statements. This pledge of allegiance to his mining heritage is the foundation for Shoupe's current fight against mountaintop removal. His grandfather began working in the coke ovens around Lafollette, Tennessee, before moving to Wallins Creek in Harlan County and going into the mines. Shoupe's father, Buster, better known as Buck, followed him underground.

“My dad is a hero to me,” Shoupe admits, gazing across the freshly mowed grass to the coal miner's statue.

Buck Shoupe was active in the legendary fight for unionization in Eastern Kentucky during the 1930s. While on the picket line at Crummies Creek, he was shot in the hand.

“Back in those days, they were these company baseball teams,” he says. “Each coal company had their own team. Dad was a tremendous hind-catcher. He could've got a job anywhere, being a baseball player. But then he got shot. That ruined his baseball career.”

The injury didn't wound Buck's determination. After he recovered and the strike ended, Buck Shoupe went back down in the mines. He also continued his fight for a better working environment through the United Mine Workers, even picketing with them in his old age during the Brookside strikes. He can be glimpsed, along with his son, in

Harlan County USA

.

“I don't know if I should say this or not, but, well, he's dead and gone anyway, so it don't matter: that shot of all them guns in the back of the car?” Shoupe recalls, describing a scene in the

film. “That was my dad's car. He was old at that time, too, but he feared no man. He didn't fear anything but God. He was still fighting.”

Buck Shoupe's son's blood also runs red with that mountain courage. Like many other men and women of a certain age from Appalachia, it's what carried him through the jungles of Vietnam just as the war began in full force in the mid-1960s. And like many other of his fellow veterans, his time in country is something that he doesn't like to talk about.

“That year-plus I spent in Vietnam, pretty much, it messed me up,” Shoupe stumbles. He looks down at his brown sandals for a moment. “I didn't realize it at the time. I hain't going to lie about it; I still have problems with it today.”

He dealt with his problems by coming home and drinking with buddies. Seven of them headed to Louisville to find work, all crowding into a two-bedroom apartment. Shoupe quickly returned. Homesick for his family and his land, he took up the family trade and went underground.

He looks back: “Joe Hollingsworth—he's dead and gone now—he liked my dad. He said, ‘Yeah, that old Buck Shoupe's a good worker; you reckon you can work as good as him?' and I said, ‘Yeah, buddy.'”

Shoupe remembers feeling confident going underground, believing he'd found his place. He relished that dawn of darkness, the rush of adrenaline that came with being a couple of miles underground.

“Coal mining as I know it, as it's been done around here for years, it's that risk,” he says. “That's part of the culture. It's hard to explain what a deep miner is. You're a unique individual when you put that hat on and go underground and dig coal. It's a culture.”

Shoupe wasn't able to enjoy this contentment for long. Ten months later, he was critically injured when three tons of rock fell on him, mangling his body.

“It was a horseback-type thing, a huge kettle bottom about

the size of a pool table,” he explains. “I was lucky that they was enough fellers around to lift it up off of me and get me out from under it.”

By all accounts, Shoupe should have been dead. But true to his tough, mountain stock, he survived. His legs, arms, and back are permanently damaged. His spirit has been affected, too. If you listen closely, if you strain to hear the backstory that lingers between his frank opinions and down-home mannerisms, you can almost hear a deep undertone of hard-earned compassion and sweetness.

He stayed in the hospital for a year and then spent another three years recovering at home in the care of his wife, Paquita, and his mother. During his convalescence, Shoupe began taking classes at Southeast Community College in nearby Cumberland. He became a full-time union man after graduating, working as a research assistant at the United Mine Workers headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia, just outside of Washington, D.C., during what he calls “the most miserable year in my life.”

Shoupe moans, “I was so homesick when I was in D.C. I don't care to tell you, that just wasn't me. All that hustle-bustle. All them horns blowing and sirens. It took its toll on me.”

He returned home to work as an organizer during the Brookside strikes, eventually retiring in 1986. After a number of blurry years—“I got burnt out,” he says—he started noticing what was being lost around him: “If you go up the river there, you'll see that they've destroyed the very place I growed up. The places where I played in the creek and swung on the grapevines. That woke me up. I knowed that wasn't right, and for about three year now I've been fighting all I can fight.”

What finally pushed Shoupe over the edge was an effort by Black Mountain Resources, an Arch of Kentucky subsidiary, to mine under Lynch's reservoir, which provides drinking water to more than 600 residents. He contacted KFTC after seeing its advertisement in a local paper.

“They helped us a sight,” he recalls. “We started protesting

it; we didn't know how to fight it. One night we had a permit hearing over at the college, and a big bunch come down from Frankfort and they had to change their permit.”

That win was a moral victory for Lynch residents, some of whom followed Shoupe's lead and joined KFTC, forming the Harlan County chapter, which now boasts over sixty-five members.

The reservoir controversy also contributed to Shoupe's decision to run for a seat on the Benham city council in 2006, which he won handily.

It's easy to see why—he knows everybody in town. As he sits in the park, a lady wearing a trucker's cap to shade her face from the sun hustles by, walking her dog along the blacktop path carved out long ago by the phantom railroad tracks, another reminder of Benham's former glory in the heyday of deep mining.

“Hey, Louise!” Shoupe hollers.

“Howdy, Carl!” she calls back, pleased to see him.

“That's my neighbor,” he explains under his breath.

Driving through town, he tips his chin or throws his hand up to many of the passersby. It's something that people like Colleen Unroe, Harlan County's KFTC organizer, have grown accustomed to seeing.

“Carl has a lot of connections with people in the community,” says Unroe. “He is a powerful speaker who talks about mountaintop removal and valley fills in a way that people can understand. He consistently asks the hard questions of elected officials and community members alike and is always looking for an angle to get new people involved.”

Unroe calls Shoupe's union background “invaluable”: “Because of his work as a UMWA organizer, he intimately understands how the industry works. This context gives him a different kind of credibility and turns the industry's argument about jobs on its face.”

Part of the reason Shoupe feels compelled to fight so hard is to compensate for the union's absence. He is still first and foremost his father's son: a union man.

“We set by and let the union slip away,” he mourns, his face tightening in frustration. “The UMWA bears some responsibility for mountaintop removal happening. If I could talk to Cecil Roberts today, I'd say that the UMWA needs to get off their hind-end and stop supporting mountaintop removal. I'd say the union needs to get back to what it was built on: deep mining.”

He scoffs when speaking of the new mines: “These guys up here on top of these mountains pushing dirt around, they're not coal miners. I won't give them the respect of calling them coal miners. They're earth movers.”

Shoupe is indignant when he says this. His demeanor makes it clear that this is a personal insult to him, his father, his grandfather, and all the other deep miners who took such pride in both their job and their homeplace.

Such plain talk is remarkable for a politician, even on the local level. It's a trait that has served Shoupe well during his tenure on the city council, and he has combined that plain talk with bold, progressive ideas for his region's future.

“I'm trying to move toward another kind of economy,” he says. “We have the technology to move on to alternative sources. We're trying to create a wind turbine program right here. It's really looking good. MACED is on board,

2

and KFTC, of course. It looks like MIT is going to get a summer intern to come down and work with us.

3

This could be ten or twelve good-paying jobs.”

Shoupe's optimism is contagious. While many in the struggle become downcast at times, Shoupe responds by sticking out his Cherokee chin and digging in even more: “People can change things if they get together. If we have a cohesive effort, we can beat 'em. Our side is winning. Minds are changing here in Harlan.”

Shoupe also believes that minds are changing on coal issues in the halls of Congress nearly five hundred miles away. In April 2008, he returned to Washington, his former home, to participate in the third annual Mountaintop Removal Lobby Week. Along with 125 other citizen lobbyists, Shoupe made his rounds through

congressional offices on Capitol Hill to drum up more co-sponsors for H.R. 2169, the Clean Water Protection Act. Dividing into groups of four or five, the delegation visited over 110 House offices and talked to more than 30 senators or staffers about introducing a companion bill in the Senate.