Sparks in Scotland (20 page)

Read Sparks in Scotland Online

Authors: A. Destiny and Rhonda Helms

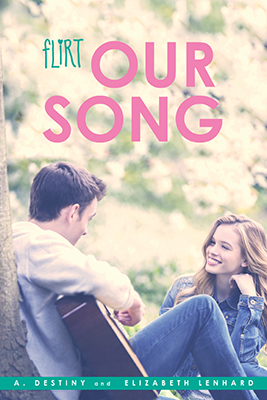

TURN THE PAGE FOR MORE FLIRTY FUN.

A

t the Winnie C. Camden

Folk School, all the sounds are peaceful and antiqueâthe pling, pling, pling, of hammer dulcimers, the sleepy grind of katydids, the whoosh of fire in forges and kilns. While people are here, whether it's for a weekend workshop oran entire month of quilting or wildflower painting, they will themselves to become antique, too. They pretend they've never heard of Twitter or texting. Somebody always seems to be singing, “Tis the gift to be simple, tis the gift to be free. . .” But me? When I arrived at Camden on the second day of June, my summer barely begun, I made way too much noise. I didn't mean to. (Not entirely, anyway.) But I was driving my grandma's stiff and wheezy van, lumbering from too much cargo. The slightest turn of the steering wheel in the Camden parking lot unleashed a spray of gravel. And when

I'd parked and stumbled out of the driver's seatâstiff and sore after the four-hour journey from Atlanta to North CarolinaâI accidentally slammed my door.

At least, I think it was an accident.

Maybe I was just bad with cars. I'd only had my learner's permit for three weeks.

“Please remind me why I agreed to let you drive?” my grandma asked as she creaked out of the passenger seat and shuffled toward the back of the van.

I circled around, too, meeting Nanny by the trunk.

“Because you have an iron stomach and I always get carsick up here?” I offered. Camden lay in a valley blockaded on all sides by mountains. The only way to reach it was along nauseatingly twisty roads.

“Or, maybe,” I posed, smiling slyly as I leaned against our van's dented bumper, “you feel terrible for dragging me to no-wifi Âpurgatory for the entire summer.”

“Well, let me think on that,” Nanny said, tapping a short-nailed fingertip against her pursed lips. “Do I feel bad for bringing you here for four weeks out of your nine-week summer? Do I feel guilty for asking you to assist in my fiddle class after being your one and only music teacher since you were three?”

I squirmed as Nanny moved her finger to her chin and pretended to give these questions serious consideration.

“Do I feel sorry for you,” she went on, “because you broke curfew one too many times and your parents sent you here, to

one of the most beautiful places on earth, as âpunishment?'”

Nanny made exaggerated air quotes with her fingers.

I folded my arms and sighed. I should have known not to give my grandma that easy opening. Maybe it was being a musician that gave her such perfect pitch for sarcasm. Once she got on a roll, she could improv forever.

Nanny gazed at the sky and mock-contemplated for another beat before she looked at me and grinned.

“Nope, my conscience is clear,” she said. “But thank you for your concern, Nellie.”

I rolled my eyes, but couldn't stifle a tiny snort as I popped open the trunk door. That was another talent of Nanny's. She could make me laugh even as she was doing something hideously parental like carting me off to folk music jail and calling me “Nellie” instead of Nell.

I started to pull our fiddle cases and bags out of the van, but before I could hand anything to Nanny, she'd set off across the parking lot, stretching her wiry arms over her head.

“What about our stuff?” I called after her.

Still walking, she tossed her answer over her shoulder.

“We'll get 'em after we check in.”

There was an eagerness, even a little breathlessness, in her scratchy voice.

I'd almost forgotten that, as full-of-dread as I was about this summer, that's how excited Nanny was. She'd been teaching fiddle classes here for way longer than I'd been alive. Only birth or death

kept her from her Camden summersâliterally. She'd stayed home the summer that I was born fifteen years ago, and then again when my brother Carl arrived.

Then, when Carl was four and I was nine, my grandfather got sick, very sick. Nanny cancelled her month at Camden once again. A few weeks later, PawPaw died. That's when Camden came to Nanny. In the over air-conditioned funeral home, one of the textile teachers draped Nanny's shoulders in a beautiful, hand-knitted shawl. A couple wood carvers spent a whole night etching gorgeous designs into PawPaw's simple casket. And, oh, the music. The music never stopped.

That helped most of all. Because in our family, music is the constant, the normal. Somebody is always picking or bowing, strumming or singing. On any given day in our houseâand in Nanny's down the streetâthere are recordings happening in the basement and lessons being conducted in the front parlor. Dinner parties don't end with dessert but with front porch jam sessions.Nanny, my Âparents, and their many musician friends stick to Irish, Appalachian, folk and roots music, anything so long as it's really old. Bonus points if the lyrics involve coal miners with black lung or mothers dying in childbirth.

The strumming, singing, plinking is so constant, I barely hear it anymore. Music is the old framed photos that cover our bungalow walls, our faded rag rugs, and our tarnished, mismatched silverwareâtreasures to some, wallpaper to me.

Maybe that's why, as I followed Nanny onto the Âstudent-Âcrowded

lawn in front of the Camden lodge, it took me a moment to realize that somebody was playing a fiddle. It only registered when I saw Nanny veer away from the beeline she'd been making to the lodge. Then I noticed other students milling around the lawn cocking their heads, grinning, and following Nanny to a circle that had gathered around the musician playing the song. The tune was clear, sweet, strong, and of course, very vintage.

From the outskirts of the small crowd that had gathered, I couldn't see the fiddler. I could only glimpse the tip of his or her violin bow bobbing gracefully against the sky. But I didn't mind. I took a step back so I could eye the spectators instead.

Camden was one of those “ages nine to ninety-nine!” kind of places, so I wasn't surprised to see some earth-mamas with long braids trailing down their backs, men in beards and plaid, and grandparent-types wearing sensible sandals and sunhats. A lot of the kids were just thatâkids. They looked a lot more like my ten-year-old brother than like me. They were Âprobably here because they dreamed of being Laura Ingalls Wilder or Johnny Tremain. I knew this because the last time I'd come to Camden, as an eleven-year-old, I'd wanted to be Anne of Green Gables.

But soon after that, I'd started to find the Camden school too earnest, too stifling. It was the only place, outside of Santa's workshop, that I associated with the word jolly.

There were clearly plenty of teenagers here who didn't feel

the same way. A few of them were in this group listening to the Âfiddler. There were two guys with patchy facial hair, wearing Âserious Âhiking boots and backpacks elaborately networked with canteens and compasses.

There was also a girl who looked about my age. Her pink cheeks looked freshly scrubbed. Her long, sand-colored hair was plaited into braids that snaked out from beneath a red bandana. She wore black cargo shorts and white clogs.

Since she was engrossed in the violin music, I could stare at her and wonder which class she was taking. She didn't seem like a spinning/knitting typeâthey always wore flowy layers and smelled faintly of sheep. Maybe she was a quilter or a basket weaver? Orâ

Soap, I decided with a nod. That had to be it. She was here to make beautiful, scented soaps molded into the shapes of flowers and fawns and woodland mushrooms.

Having made up my mind about Soap Girl, I turned in the other direction. My eyes connected immediately with those of another teenage girl. She'd taken a step back from the circle and she was clearly sizing me up.

I gave her a cringey smile.

Caught me, I mouthed.

She laughed and headed toward me.

Or should I say, she wafted toward me. Everything about this girl was light and fluttery, from her long black hairâa cascade of glossy, tight ringletsâto her blowsy, ankle-skimming skirt. Her

skin wasn't just brownâit was brown with golden undertones. The girl practically glowed.

When she reached me, she gave me a mischievous smile.

“You were totally judging that girl over there, weren't you?” she said.

“Um,” I stammered. “I think judging is kind of a harsh way to put it, but. . .”

“What class do you think she's taking?” the girl asked.

“Soapmaking,” I said quickly. “Definitely soapmaking.”

“See?” she said, a gleeful bubble in her voice. “You're wrong. I asked her a few minutes ago and she's taking canning.”

“Canning?”

“Oh, it's a new class Camden added,” the girl said with a graceful flick of her hand. “You know, jams, jellies, pickles. Anything you can put in a jar. I'm from New York and it's the thing up there. You can't throw a rock without hitting somebody in a slouchy hat carrying a box of mason jars. And probably a messenger bag full of bacon. Not that I would ever.”

“Throw a rock at somebody?” I asked. I was kind of having a hard time following this girl. For somebody who looked so zen and wispy, she sure talked fast.

“Or eat bacon,” she replied. “Anyway, I'm Annabelle. I'm taking pottery.”

Of course you're taking pottery, I thought, suppressing a Âgiggle. But what I said out loud was, “Oh, cool. Pottery's fun.”

“Oh, it's more than fun,” she said. Then she launched into an

explanation of her choice, talking so excitedly that I could only make out a few snatched phrases.

“I need to live before I head to college in the fall . . . reach deep into my inner being . . . suck the marrow out of life . . . not just a taker, you know, but a maker . . . I'm taking pottery as a way to get back to the earth . . .”

When she seemed to be done with her monologueâwhich had more twists and turns to it than a mountain road, I smiled, nodded hard and said, “That's great! You go!”

Luckily, Annabelle didn't see my vague response for what it was: I have no idea what you just said.

Instead, she'd clasped her hands in front of her chest and looked a bit misty-eyed as she said, “Thank you for that validation. Really.”

“Um, no problem,” I said. “By the way, I'm Nell.”

“No. Way,” Annabelle said, her dark eyes widening. I noticed that her lashes were as lush and curly as her hair.

“Yes, Nell,” I sighed. “I know it must sound like a hopelessly hillbilly name, especially to someone from New York. My family. . .”

“Nell,” Annabelle said with a frown. “First of all, never apologize for your name. Your name is an essential part of your identity. Second of all, if you're Nell Finlayson, you're my roommate!”

I blinked.

“Well, I am Nell Finlayson,” I said, “so I guess I am. Your roommate I mean.”

As I said this, I felt a mixture of excitement and panic.

ÂAnnabelle clearly had what adults called a “strong personality.” The thing is, I'm pretty sure the adults hardly ever mean that as a Âcompliment.

“So, Nell, how old are you?” Annabelle demanded bluntly.

“Fifteen,” I said.

“I'm two years older than you,” she replied. “Which means, I'm in a position to give you some advice.”

“More advice, you mean?” I said, before I could stop myself.

Annabelle didn't seem to notice. Instead she looped her arm through mine. We were about the same height, five foot seven, but next to her willowy goldenness, I felt washed out and shriveled. Her clothes were a rippling rainbow of plum and teal, mustard and aqua. Meanwhile, my skinny capris were dark gray and my tank top was the brooding color of an avocado peel. My hairâfreshly blunt cut and flatironed to a crispâwas dyed black. Only my feet had a bit of brightness to them. I was wearing my favorite, acid-yellow, pointy-toed flats.

“Check out that,” Annabelle ordered me. She pointed at the disembodied fiddle bow, which was still doing its little dance in the center of the crowd.

I glanced at it, then shrugged at Annabelle.

“I'm not talking about the instrument,” Annabelle insisted. She grabbed me by the shoulders and shuffled me sideways until we were able to peek through a break in the crowd. “I'm talking about the player!”

I followed her gaze to the musician

And then I caught my breath.

The fiddler was a boy.

A boy who was clearly in high school. (His cut-off khakis, orange-and-green sneakers, and T-shirt that said,

ASHWOOD HIGH SCHOOL CROSS COUNTRY

were a hint.)

I might have also noticed that the boy's eyes were a deep, beautiful blue. You could see the color even though he was wearing glasses with chunky, black frames. His glossy, dark brown hair flopped over his forehead in a particularly cute way. His nose had just a hint of a bump in the bridge and I could tell that his torso was long and slim beneath his faded yellow T-shirt.

And, oh yeah, his playing was beautiful, too. Maybe even a notch above boring. His style was studied, sure. His rhythms were too even and his transitions were too careful to be untrained. He was clearly one of those Practicers that Nanny had always wanted me to be (but that I never had been).

But he also had talent.

No, more than thatâhe had The Joy.

The Joy makes you play until your fingertips are worn with deep, painful grooves.

The Joy makes you listen to all 102 versions of Hallelujah until you can decide which interpretation you love the best, even if it drives the rest of your family crazy.

And The Joy makes your face contort into funny expressions as you play.

I couldn't help but notice that, even while this boy was grimacing and waggling his eyebrows during the climax of his song, he still looked pretty good.

And when he stopped playing? When his thick eyebrows Âsettled into place, his forehead unscrunched and his pursed lips widened into a smile while the crowd applauded for him?

Well, then, he became ridiculously good looking.