Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (62 page)

Read Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America Online

Authors: Harvey Klehr;John Earl Haynes;Alexander Vassiliev

In 1949 FBI agents arrested Judith Coplon, a U.S. Justice Department analyst, in the act of turning over justice Department documents

to Valentin Gubichev, a Soviet intelligence operative working under the

cover of employment by the United Nations. Two different federal courts

convicted her of espionage-related charges in 1949 and 1950. However,

with one of the appeals court judges commenting that her "guilt was plain," in both cases her convictions were overturned on legal technical-

ities.'69

Coplon attended Barnard College, where she participated in student

groups aligned with the Communist Party. After graduation in 1943 she

got a job with the New York office of the Economic Warfare section of the

U.S. Justice Department. Among her Barnard college friends was another young Communist, Flora Wovschin, already a KGB source, reporting to the Soviets on her work at the Office of War Information.

Wovschin was also an energetic talent spotter for the KGB, drawing a

number of young Communists into Soviet espionage. One of her recruits

was her friend Judith Coplon.

It was not until January 1945 that Vladimir Pravdin of the KGB New

York station met with Coplon and formally recruited her. To the KGB's

delight, she had already obtained a highly desirable post in the Foreign

Agents Registration section of the justice Department in Washington.

Anyone acting on behalf of a foreign government had to register with the

Justice Department. Those legitimately hired by foreign governments as

lobbyists or publicists routinely registered, but for obvious reasons, those

engaged in espionage did not. While other laws also criminalized espionage, this one provided a simple statutory basis for federal investigation

and prosecution of covert agents working for foreign powers. Consequently, Coplon's section of the justice Department worked closely with

the FBI, which furnished it with reports of counterintelligence investigations so that its staff could determine when the evidence would support

arrest and prosecution. Coplon was in a position to give the KGB notice

when one of its operatives was under investigation and allow it to warn its

agents to cease activity and destroy evidence. 170

Pravdin reported to Moscow Center that he had been impressed by

his recruitment meeting with Coplon:

"She gives the impression of a very serious, modest, thoughtful young woman

who is ideologically close to us.... There is no question about the sincerity of

her desire to work with us. In the process of the conversation S. ["Sima"/

Coplon] stressed how much she appreciates the trust placed in her and that,

knowing whom she is working for, from now on she will redouble her efforts.

In the very first phase of her work with Zora [Wovschin], S. assumed that she

was assisting the local fellowcountrymen [CPUSA]. Subsequently, from her

conversations with Z. and based on the nature of the materials that were requested from her, she figured out that this work was related to our country.

When Sergey [Pravdin] asked how she had arrived at this conclusion, S.

replied that she knew about Zora's past connections with the [Soviet] con sulate; besides that, she thought that the materials she was obtaining couldn't

be of interest to the fellowcountrymen but could be of interest to an organization like the Comintern or another institution linked to us. At the same time

she added that she had hoped that she was working specifically for us, since

she considered it the greatest honor to receive an opportunity to give us her

modest assistance."

Although initially concerned that she was moving too aggressively to steal

documents before her position was secure, the KGB was well pleased

with Coplon. In August 1945 the New York station told Moscow Center:

"`She treats our assignments very seriously and conscientiously and considers our work the main job in her life. This serious attitude is borne out

by her decision to back out of marrying her former fiance because otherwise she wouldn't have been able to continue working with us."' Perhaps as partial compensation for this sacrifice, the KGB New York station

noted it had given Coplon a cash bonus to help buy furniture for her new

apartment in Washington.171

From 1945 until her arrest in 1949 Coplon copied and turned over to

the KGB numerous FBI and counterintelligence documents. The Venona

project, however, ended her career as a Soviet spy. In late 1948 several

deciphered KGB cables indicated that the KGB in 1945 had a source,

cover-named "Sima," working in the Foreign Agents Registration section

at the justice Department in Washington and that "Sima" had been in

New York in 1944 working for the Economic Warfare section of the Department of Justice. The FBI quickly established that only one person fit

those criteria: Judith Coplon.

Hoping to catch her in the act, the FBI had her superiors at the justice Department show her a fake FBI report about a source inside Amtorg reporting on Soviet activities. She took the bait and traveled to New

York, where she was arrested after meeting Gubichev in March 1949. In

her purse she had not only a portion of the FBI "bait" material, but also

thirty pages of notes, reports, and copies of government documents, including extracts from Foreign Agents Registration section "data slips"

that summarized FBI reports on thirty-four specific espionage investigations.

Coplon turned over a considerable volume of documents on FBI

counterintelligence operations to the KGB. One of the earliest reports,

from March 1945, alerted the KGB that the FBI and the Justice Department, after earlier emphasizing German, Japanese, and domestic fascists, had shifted priorities: "The Club's [Foreign Agents Registration section of the justice Department's] main focus, according to Sima [Coplon], is on Sov. institutions and fellowcountrymen [Communists].... The Club

has abundant archives and a card catalog, compiled from the information of the Club, the Hut [FBI], the Cabin [OSS], and the milit. and nav.

intelligence agencies. She has been instructed to closely study the review

procedure." An October KGB report stated:

Sima removed from the Club's card catalog duplicates of Hut memoranda containing agent materials on the investigation of Sov. institutions, the fraternal

[CPUSA], progress. orgs, polecats [Trotskyists], White monarchists [anti-Bolshevik Russians], etc. A portion are outdated...... It's obvious from the materials what a meticulous record is made of the tiniest facts from discussions,

correspondence, and phone conversations conducted by our organizations, individual representatives, and operatives in the country. What is notable is large

numbers of Hut personnel who are engaged in the above investigations."

Coplon also furnished the KGB information about a contact of Gregory

Silvermaster who was under FBI surveillance; its first confirmation that

it had been Armand Feldman whose information had led the FBI to arrest Gayk Ovakimyan in 1941; news that the FBI continued to investigate people associated with Jacob Golos, even though he had died in

1943; reports on FBI wiretapping of San Francisco Bay Area Communists; and a list of the people identified to the FBI as hidden Communists

in Washington by Catherine Perlo, the estranged ex-wife of Victor

Perlo.172

After legal technicalities overturned Coplon's two convictions, the

Justice Department kept her indictments alive for some years, hoping it

could find a way around the rulings that had precluded its use of its best

evidence (the stolen justice Department material found on Coplon at the

time of her arrest). But in 1967 the justice Department dropped the indictments. Coplon married one of her defense attorneys and later opened

a restaurant in New York.

The dozens of Soviet sources who supplied information that came to

them as part of their duties as employees of the U.S. government gave the

Soviet Union a unique insight into all aspects of Washington affairs. Not

every source occupied a sensitive post or had access to valuable material.

Nor were all of them productive; some handed over materials grudgingly

or only occasionally. But others were able to inform the KGB of highlevel policy deliberations and decisions; supply highly classified data on diplomatic, political, or military capabilities or plans; or identify and

sometimes recruit other sources. Some were able to deflect investigations of friends or prevent their dismissals. And, as insurance, the KGB

also recruited sources with access to American counterintelligence investigations to monitor the danger its agents faced and to warn them

when they were in jeopardy.

While a handful of the spies in the American government were mercenaries-notably David Salmon and Samuel Dickstein-the vast majority were Communists or Communist sympathizers who took little profit

for their activities but willingly supplied information out of devotion to

the Soviet Union and the Communist cause.

Office of Strategic Services

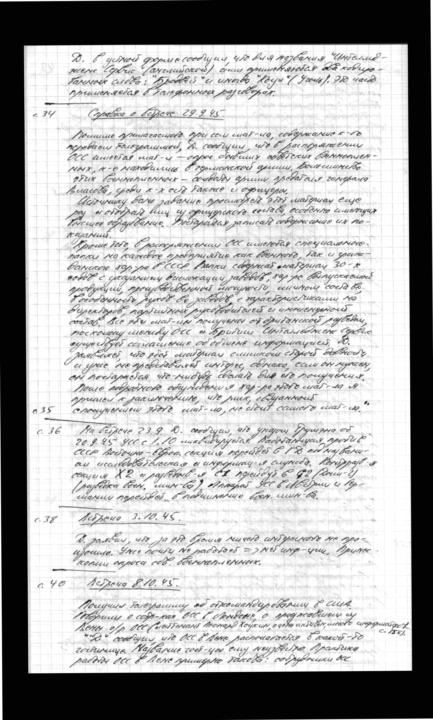

Report on a 1945 meeting between a KGB officer in London and Stanley Graze, a Soviet source inside

America's World War II intelligence agency, the Office of Strategic Services. Graze provides information

about OSS operations in Vienna. Courtesy of Alexander Vassiliev.

he KGB regarded the Office of Strategic Services, America's

he KGB regarded the Office of Strategic Services, America's

World War II intelligence agency, as a prime target and developed an astounding number of sources within it. Documents in

Vassiliev's notebooks contain details about twelve of them. This

success was due in part to the vulnerability to infiltration provided by the

speed and organizational chaos that attended OSS's development. Remarkably, the United States did not possess a foreign intelligence service

until 1942. Various government agencies carried out foreign intelligence,

but their activities were uncoordinated, episodic, and frequently amateurish. The War Department's Military Intelligence Division focused on

battlefield intelligence and security (counterintelligence). Military attaches at American embassies occasionally recruited sources and conducted espionage operations, but such efforts were usually the product

of an aggressive individual officer and evaporated on his routine reassignment. Other than purely military "order-of-battle" appraisals of the size and capabilities of foreign forces, there was little institutional support

by the Army or Navy for strategic, diplomatic, and political intelligence,

while the State Department regarded espionage as incompatible with its

diplomatic mission. Famously, Secretary of State Henry Stimson, learning in 1929 that the State Department was funding a small code-breaking operation to read diplomatic ciphers, had it shut down, indignantly

observing, "Gentlemen don't read each other's mail."'

After war began in Europe in 1939, President Roosevelt realized the

woeful inadequacy of American intelligence capability. He appointed

William Donovan, a Wall Street lawyer and World War I military hero, as

"Coordinator of Information" in July 1941, with a mandate to systematically compile information of strategic value. When the United States entered the war, Donovan's office split, with its propaganda arm becoming

the Office of War Information and its intelligence arm becoming the Office of Strategic Services, with Donovan in command. The OSS reported

to the joint Chiefs of Staff, and many of its personnel held military rank,

including General Donovan. The OSS was America's first foreign intelligence agency. It systematically collected and analyzed military, strategic,

diplomatic, and technical intelligence. OSS operatives recruited and ran

agent networks in foreign nations and also set up special operation units

that assisted underground resistance forces and engaged in sabotage and

behind-the-lines combat operations.