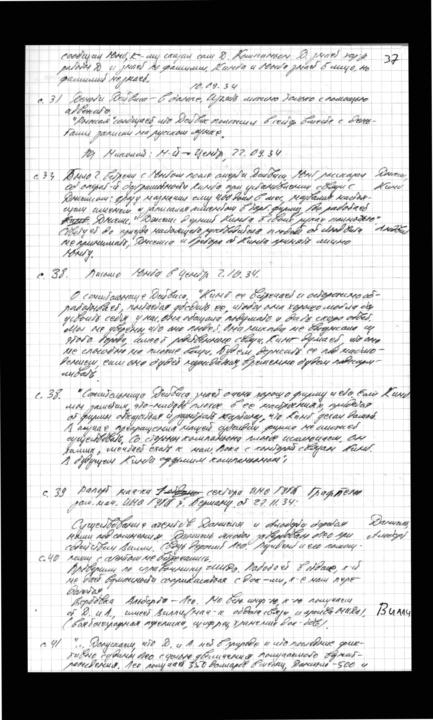

Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (44 page)

Read Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America Online

Authors: Harvey Klehr;John Earl Haynes;Alexander Vassiliev

Ovakimyan, however, was arrested by the FBI shortly after receiving

Moscow Center's instructions. It was not until November 1941 that the

New York station reported that it had established contact with Steiger and

learned that he worked at CBS, compiling summaries of international radio

reports for broadcast and distribution to newspapers. Despite the delay,

Steiger was willing to renew contact and reported that he "can obtain interesting information." "Fakir" appears in the Venona deciyptions as an

unidentified cover name (later redesignated "Arnold"), and the deciphered

cables show that Steiger during 1943 and 1944 supplied the KGB with information of a foreign policy/diplomatic character that presumably came to

his attention or from contacts he developed as a journalist.33

One journalist associated with Soviet intelligence spent only a few

years in the United States, from 1945 to 1951, before returning to China,

where he had first been recruited. Israel Epstein was born in Warsaw in

1915; he moved to Tianjin, China, at the age of two with his Marxist parents. A 1949 KGB report listing sources available for use suggested:

""Minayev"-Israel Epstein, a journalist. An agent since '37, recruited

in China. Came to the USA in 45. Lives as a resident alien. Gained

Soviet citizenship in 43, but his papers were not issued for oper. reasons. "s4

Moscow had first alerted the New York station about Epstein in 1943

during a critical review of its progress on developing sources on China.

Moscow Center warned that the United States was increasing its engagement with China and the KGB needed to respond, explaining:

"While the elaboration of issues related to the course of the war in Europe and

issues of postwar Europe is one of the leading areas of the office's everyday activities, the office is clearly not giving enough attention to coverage of issues

related to the war in the Pacific and U.S. policy toward the countries of the Pacific. Meanwhile, our operatives in Chungking and in Sinkiang note an exceptional increase in the Americans' activities in China and their effort to penetrate into China's northwestern provinces, to the border with the USSR and

the MPR [Mongolian People's Republic]. For example, in the winter of this

year a group of American competitors toured all of northwestern China up to

our border with Sinkiang. The group consisted of. Clabb, second secretary of

the U.S. Embassy in Chungking; Lieutenant Roy assistant military attache;

Adler, a financial expert, and others. We have information regarding the

planned opening in a number of northwestern Chinese cities of American consulates and regarding the intention of the U.S. to finance the development

of natural resources in northwestern China.

The Americans are taking every measure in order to seize the moment and

maximize their influence in China: they are providing a great deal of financial

assistance to Chinese higher educational institutions, they are creating and

subsidizing `young men's Christian associations, etc.' . . . In our cable of 9.11-

1942 we gave you the task of cultivating through "Girl Friend" [Fairfax-

Cholmeley] and other probationers of the office the activities of members of

American organizations that deal with issues related to China and editorial

staffers of magazines: Asia, China Today, Amerasia, Pacific Affairs, and others

that publish articles on countries of the Pacific and on issues of U.S. Pacific

policy. To date we have no materials from you that would indicate that the station is performing this task.

In connection with the forthcoming departure of "Girl Friend's" husband,

"Minayev" [Epstein], we are giving you the task of intensifying the cultivation

of the above-mentioned contingent. A large number of these individuals regularly visit China, and they could be extremely useful to us in cultivating the

leading Chinese circles and the activities of foreign missions in China. We are

interested in the structure of numerous organizations, institutes, associations,

and various societies that manage the study of the Pacific problem, especially

the Pacific Institute, whose regular session was held in December 1942 in

Canada. To what extent is their work directed by the "Bank" [U.S. State Department] and competitor [American intelligence] organizations?"

Elsie Fairfax-Cholmeley, Epstein's wife, worked for United China Relief

in New York. She was the daughter of Christian missionaries in China

and also a Communist. "Girl Friend" was unidentified in the Venona de-

clyptions but listed as an asset of the KGB New York station who was put

into "cold storage" in 1944•s5

Arriving in the United States in 1945, Epstein wrote for Allied Labor

News; became active in the Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern

Policy, which supported the Chinese Communists; and in 1947 published

The Unfinished Revolution in China, an unabashedly partisan celebration of the Communist movement in China. In 1950 the plan of work for

the KGB Washington station assigned "Minayev"/Epstein the duty of

"covering the activities of Amer. left trade unions." He and Elsie, however, left for China in 1951, where he became editor of a PRC Englishlanguage journal, China Reconstructs, later renamed China Today, and

served as a correspondent for the National Guardian, edited by another

former KGB agent, Cedric Belfrage. Fanatically devoted to Chinese communism, he was part of a team charged with translating Mao's works into English beginning in 1960. Other members included such one-time KGB

sources as Frank Coe and Solomon Adler. When Anna Louise Strong,

another ex-KGB agent, settled in the PRC, Epstein became close to her

as well. Despite his long service to the Chinese Communist movement,

he and his wife were arrested during the Cultural Revolution in 1967 and

served five years in prison before being released with an apology. His

faith unshaken, he claimed that his imprisonment had "helped improve

him by shrinking his ego. "86

Epstein was restored to his editorial position and became a member

of the Standing Committee of the National Committee of the Chinese

People's Political Consultative Conference. In 1982 he returned to the

United States for a reunion conference of reporters who had served in

China; he harbored no doubts or second thoughts about his life or causes.

Elsie died in 1984. Israel Epstein died in May 2005.87

The myriad of ways that journalists assisted the KGB-as sources of inside information, talent spotters, purveyors of disinformation and propaganda, couriers-is testimony to how valuable they were perceived as

being. Those profiled above do not exhaust the list of journalists who cooperated with Soviet intelligence. Samuel Krafsur ("Ide"), CPUSA member and veteran of the International Brigades, an asset of the KGB New

York station, worked as a journalist for TASS. The KGB used Krafsur to

cultivate American journalists with particular attention to recruiting some

as KGB sources.ss Cedric Belfrage ("Charlie"), an Englishman who later

edited the National Guardian, wrote angry books denouncing what he

depicted as a paranoid America's anti-Communist "inquisition," which

looked for non-existent spies. A concealed Communist, he worked for

British Security Coordination, a branch of British intelligence, in the

United States during World War II. He reported both British and American information to the New York office of the KGB.89 Richard Lauterbach ("Pa"), a Time magazine Moscow correspondent, carried out discussions with Jack Soble (an illegal KGB officer) that led the New York

station to ask Moscow Center for sanction for his formal recruitment, but

it is unclear if this relationship was consummated.90 Johannes Steele

("Dicky"), radio commentator and columnist, assisted the KGB with contacts with refugees and exiles.01 Ricardo Setaro ("Express Messenger"

and "Jean"), deputy chief of the Latin American department at CBS

Radio, worked as a courier and communications link for KGB South American operations.92 Helen Scott ("Fir") was a journalist and KGB

source who worked as a secretary to a French journalist, Genevieve

Tabouis, and later for the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs and the

U.S. Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis War Criminals.93 Peter

MacLean ("101st") was a reporter and photojournalist who did unspecified work for Soviet intelligence, likely for GRU, in the mid-193os.94

David Carpenter ("103rd"), one-time reporter for the Baltimore Sun and

later for the Daily Worker; was part of Whittaker Chambers's GRU-linked

193os espionage apparatus.95 "Bough" was an unidentified journalist who

provided information on senior American journalists in 1944-45.96

By the early 195os nearly all of the KGB's sources, including the journalists, had dried up. A number had been exposed by defectors or tracked

down by the FBI. Others had quietly dropped away or lost contact with

Soviet intelligence. A handful had left the country. One of the last journalists to remain available for KGB use was a prominent and open member of the CPUSA. James Allen, born Solomon Auerbach, graduated

from the University of Pennsylvania and later taught philosophy there.

Fired for radical activities in 1928, he joined the CPUSA and wrote for

the Daily Worker before editing the Southern Worker and serving as one

of the party's leaders in the South. He also wrote major party tomes on

the Negro question. In the late 1930s he served as the Comintern's representative in the Philippines. In addition to service as the Daily Worker's

foreign editor, he later headed International Publishers.

Since virtually his entire adult life had been spent within the orbit of

the CPUSA, Allen was unlikely to be a source of much significant intelligence in his own right. Yet in 1949 a plan of work for the KGB New

York station noted that KGB co-optee Valentin Sorokin handled the connection with ""Jack"-James Allen, CPUSA member, no permanent

place of employment, works at a progressive press agency. Puts together

reports on econ. questions, Amer. political figures, and the CPUSA."

From the point of view of operational utility, use of an openly identified

Communist journalist whose entire career had been within the CPUSAs

organizational environment and who was well known to American security agencies was not optimal tradecraft. A senior Moscow Center official referred to the Washington station's use of James Allen as following

the "path of least resistance." Using him was a measure of the reduced circumstances of the KGB compared to the halcyon days of the 1930s and

1940s, when such established journalists as I. F. Stone, Robert S. Allen,

Ludwig Lore, John Spivak, Frank Palmer, Winston Burdett, and others

covertly worked with the KGB.97

That these journalists did less immediate damage to American interests than such government spies as Alger Hiss or scientists like Theodore

Hall should not diminish their importance to the KGB or the harm they

inflicted on American society. Unlike government employees or scientists who broke the law by turning over classified information to the KGB,

most of the journalists profiled in this chapter violated no statute of that

era. Few had any access to secret data. Members of a profession dedicated to openness, however, they covertly enlisted in an organization dedicated to deception. They used their access to information to deceive

their employers, their colleagues, and their publics about their loyalties

and veracity. They betrayed confidences and pursued political agendas

while pretending to be professional journalists. In several cases, notably

that of Stone, they later wrote prolifically about issues of subversion and

espionage without ever acknowledging that they knew far more about

how the KGB operated than they cared to express. Writing about the

American intellectuals who knowingly accepted assistance from the CIA

in the 1940s and 1950s to counter Communist influence, critics have

charged that they had been untrue to their calling. How much more apt

is the characterization directed at men who worked not for their own government, but for the intelligence service of a dictatorship?98

U.S. Government