Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (69 page)

Read Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America Online

Authors: Harvey Klehr;John Earl Haynes;Alexander Vassiliev

Mary Jane continued as a UN employee until 1951, when she and

several others were dismissed by Secretary General Trygve Lie. She claimed it was political, while the United Nations attributed her dismissal

to administrative reorganization. A UN employee panel ordered her reinstated, but Lie refused. Another panel then awarded her $6,500 in compensation. In 1952 she refused to answer questions from the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee about how she had obtained her UN

position and about Communist links. In 1953 the government indicted,

tried, and convicted her for contempt of Congress. An appeals court ordered a retrial, and in 1955 she won acquittal. The Keeneys eventually

opened an art film club.''

Jane Foster, daughter of a wealthy businessman, graduated from exclusive Mills College in 1935. She toured Europe, married a Dutch government official in 1936, and moved with him to the Dutch East Indies. On

a visit to her parents in California in 1938, she joined the American Communist Party and soon after divorced her husband. Shortly after she

moved to New York in 1941, friends introduced her to George Zlatowski,

a fellow Communist and veteran of the International Brigades. They married but George was soon drafted and sent overseas. With her Indonesian

experience and Malay language skills Foster found work with the Netherlands Study Unit, a wartime agency set up to coordinate intelligence on

the Dutch East Indies (and later absorbed by the Board of Economic

Warfare). She transferred to the Office of Strategic Services in the fall of

1943 and early in 1944 was sent to Ceylon.

Vasily Zarubin listed "`Slang,' Jane ... of the Far Eastern Department of the `cabin' [OSS]" as one of the sources recruited during his

tenure (1942-44) as chief of KGB operations in the United States. A 1957

retrospective KGB memo noted: "On a lead from "Liza" [Martha Dodd]

the agent "Slang" [Jane Foster] was recruited, followed by "Slang's" husband, the agent "Rector" [George Zlatowski], who once worked for Amer.

counterintelligence in Austria." (At the end of the war Zlatowski was serving as a U.S. Army counterintelligence officer in Austria.) After the OSS

dissolved, Jane Foster Zlatowski and her husband continued to work for

a KGB apparatus in Europe run by Jack Soble.72

The Soble network, however, included an FBI double agent, Boris

Morros (see chapter 8). In 1957 the Justice Department indicted members of the Soble ring. Jane and George Zlatowski were then in Paris and

refused to return to the United States. It appears that they may have cooperated with French security in exchange for avoiding deportation to face trial in the United States. Jane later published a memoir in which she

admitted to having been a secret Communist but denied any cooperation with Soviet intelligence.73

The dozen identified sources discussed in this chapter do not exhaust the

KGB's assets in the OSS; others mentioned in various documents have

unidentified code names. A 1945 document, for example, refers to a KGB

source in the OSS with the cover name "Akra" (variant "Akr"). Vasily

Zarubin's retrospective 1944 memo refers to several OSS sources sent to

Yugoslavia but gives no names or details. Venona decryptions of KGB cables identify two other OSS sources, Linn Farish and John Scott. Farish,

cover name "Attila," was an OSS officer who served as liaison with Tito's

Partisan forces in Yugoslavia. He died in an aircraft crash in the Balkans

in September 1944 and may have been one of those alluded to by Zarubin. In a deciphered cable discussing the Russian section of the OSS sent

in May 1942, Vasily Zarubin noted that Scott, an OSS analyst on Soviet

industry, was "our source Ivanov." David Wahl (discussed in chapter 4)

was a longtime GRU agent but shifted to the KGB in early 1945, and he

was employed by the OSS late in World War I1.74

Some of these sources, notably Donald Wheeler and Maurice

Halperin, were highly productive. Duncan Lee and Franz Neumann provided excellent material, but Moscow Center felt both fell far short of

their potential. Philip Keeney was, properly speaking, a GRU source

while at the OSS rather than a KGB source, and what he provided GRU

is unknown. Nonetheless, by any measure, the KGB's development of

more than a dozen sources in the OSS in just three years was a remarkable achievement. (In contrast, the OSS never recruited, and as a matter

of policy never even attempted to recruit, a source within the KGB.)

None of these sources served a day in prison for espionage, although

Halperin became a refugee and Foster a fugitive. Stanley Graze was indicted but for purely commercial criminal behavior. Several others were

pilloried before congressional committees and lost their government jobs,

but only Duncan Lee and Helen Tenney appeared to pay an emotional

price for their activities.

Eleven of the sources were secret Communists and came to the KGB

via the American Communist Party; in most cases Jacob Golos handled

the initial recruitment. The exception was Franz Neumann, who had

been a left-wing Social Democrat in Germany who supported an alliance with the Communists. Although the eleven Americans were secret Communists, their prior party links were not so hidden that they would have

survived an investigation had the OSS had a firm anti-Communist policy.

But General Donovan made a decision that he would allow Communists

to participate in the OSS as long as they were not blatant in their Communist partisanship. (Several Communists in the OSS displayed their loyalties so brazenly that Donovan's tolerance ran out and he fired them.)

Donovan's policy was an informal one, and in perjured testimony to Congress he flatly denied that he had ever knowingly recruited or tolerated

Communists in the OSS. Donovan's decision that the United States benefited by making use of Communist talent at the risk (and the reality) of

facilitating Soviet espionage may have been defensible at the time, but in

retrospect it was a problematic policy. Donovan also fervently sought to

establish a formal institutional relationship between the OSS and KGB,

a plan ultimately dropped due to the FBI's objections that an official KGB

presence in the United States would pose serious security problems. Vassiliev's notebooks quote or summarize a number of KGB documents on

this issue.75

President Truman's decision to dissolve the Office of Strategic Services in the fall of 1945 had, in the long run, a silver lining. The government demobilized the majority of OSS personnel, closed its offices, and

shut down most of its agent networks. It dispersed OSS remnants to the

State Department and to the joint Chiefs of Staff, where they were

treated as unwanted guests. The result was a dearth of knowledge and

information as American policymakers confronted one crisis after another

in the chaotic aftermath of World War II, while Communists, antiCommunists, and non-Communists of various sorts squared off for control of Europe and East Asia. By 1947 Truman realized the United States

needed a robust foreign intelligence agency, and at his urging Congress

passed the National Security Act of 1947, which created the Central

Intelligence Agency. The new CIA brought together the remnants of the

OSS and recruited a number of veteran OSS officers and staff, but this

time security was much more thorough. Created to fight the Cold War,

the new agency subjected all of its personnel to background checks to remove those with Communist ties. None of the persons now known to

have been KGB or GRU sources within the OSS or to have had Communist ties made the transition into the CIA. It would be many years before the KGB developed any sources within the CIA, and its later successes, to the extent they are known, never came close to its impressively

thorough infiltration of the OSS.

Technical, Scientific, and Industrial Espionage

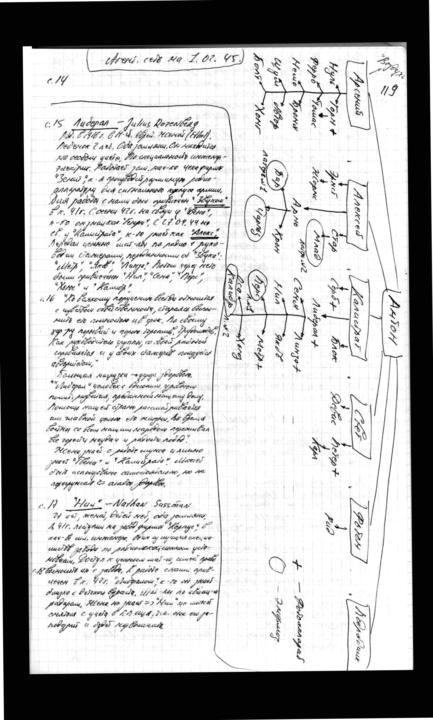

KGB scientific and technical agent network in 1945 and description of the members of Julius Rosenberg's

espionage apparatus. Courtesy of Alexander Vassiliev.

echnical, scientific, and industrial espionage lacks the glamour

echnical, scientific, and industrial espionage lacks the glamour

of diplomatic and political intelligence (atomic espionage excepted). Nonetheless, technical intelligence, called the "XY

line" in KGB jargon, was the "meat and potatoes" of KGB work

in America. In 1934 Moscow Center reminded its American officers:

"`Nowhere is technology as advanced in every sphere of industry as in A.

[America]. The most important thing with regard to the procurement of

tech. materials for our industry is that the scale of production in A. has the

closest correspondence to our scale of production. This makes tech. intelligence in the USA the main focus of work."' To fulfill that priority, the

KGB actively sought out and recruited dozens of technical sources. A

1941 KGB report broke down the occupations of its American agents in

the prior decade; forty-nine were engineers-more than half of all the

agency's sources. A 1943 report on the XY line in America listed twentyeight active American sources being handled by five KGB officers. This

report further described the sources as including eleven chemists and bacteriologists, six radio and communications specialists (mostly engineers), five aviation sources (again chiefly engineers), four who worked on

various types of high-tech "devices," one naval technology specialist, and

one nuclear specialist. Aside from those involved in atomic espionage

(discussed in chapter z) few of the KGB's technical sources ever became

prominent or the subjects of newspaper headlines; nonetheless, they provided the Soviet Union with vital industrial, military, and technological secrets. They included a few long-serving agents and more than a few eccentrics. A number of long-standing controversies about Soviet sources

can also be answered by the newly available documentation.'

Documents in Vassiliev's notebooks significantly deepen what is known of

the most successful KGB technical intelligence network, the group of

Communist engineers organized by Julius Rosenberg. The material identifies two additional members of Rosenberg's apparatus and confirms and

expands what was known from trial testimony, FBI investigations, and

Venona deciyptions about other members of his ring. The most surprising revelation is that Julius Rosenberg recruited two sources on the Manhattan atomic project, not just his long-known brother-in-law, David

Greenglass. (The story of Rosenberg's second atomic spy recruit, Russell

McNutt, is in chapter z.)

The other previously unknown Rosenberg source was listed in KGB

cables first by a cover name only partially deciphered by the Venona project, "Tu ... ," changed after September 1944 to "Nil." The FBI, however, was unable to discover the real name behind the two cover names.

KGB documents show that the first cover name was "Tuk," and a 1945

memo identified him as Nathan Sussman, a Communist colleague of

Rosenberg's and an engineer at the Western Electric company who specialized in aviation radar. With the identification of the hitherto unknown

McNutt and Sussman, the first complete account of the remarkable size

and effectiveness of the Rosenberg network is now possible.2