Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours (16 page)

Read Startup Weekend: How to Take a Company From Concept to Creation in 54 Hours Online

Authors: Marc Nager,Clint Nelsen,Franck Nouyrigat

Most of us are totally afraid of cold-calling someone or starting a conversation with a perfect stranger. We think business has moved beyond that; door-to-door salesmen are a relic of the past, right? But in order to find out what customers want, there is much to be said for talking to people who don't know you from a hole in the wall. Interestingly enough, sometimes strangers are too nice. They don't want to tell you to your face that your idea is terrible. One way around this is to suggest that the idea is someone else's. “My colleague George has an interesting idea for a. . . .”

Once you find people who are willing to talk to you, the trick is asking the right questions. Startup Weekend attendee Nick Martin started a company called Plane.ly, a website that allows you to meet people with similar interests while you're flying. At one point he remembers talking to business owners about their needs. He laid out for them the top three problems he thought that businesses had and then asked them to put them in order. In retrospect, he thinks he was “leading the witness” a little. Why not offer more choices, and then ask your potential customers to add to the list of problems? Customer development conversations are not supposed to be interrogations; they're supposed to be dialogues. The more open-ended you can make your questions, the more useful the information you will get. It's the difference, as every parent knows, between asking a kid, “Did you have fun at school today?” and “What did you do at recess?”

Nathan Bashaw, the founder of

Thoughtback.com

and a guest speaker at a Startup Weekend in Lansing, Michigan, wrote this advice regarding interviews on his blog. It's worth a read:

Have you ever noticed how the best conversations tend to wander away from the original talking point, and head towards interesting, uncharted territory? When you're talking to potential customers, do everything you can to let these types of engaging discussions emerge. Don't stop them when they're leaning forward in their seat with their eyes wide, adrenaline surging, paying rapt attention to the conversation. I used to take a rigid, formal approach to customer development interviews until I realized that I never got many good ideas or feedback from those conversations. My scripted questions made people uneasy, and they weren't willing to open up with what they *

really

* think. Now, I don't think of these interviews as anything more than an opportunity to build a relationship and learn from an interesting person. I ask about their story, how they got started doing what they do, what they've been reading lately, where they want to be in five years. This gives me a holistic understanding that no survey will ever be able to replicate, because it takes a genuine human connection for people to feel comfortable opening up.

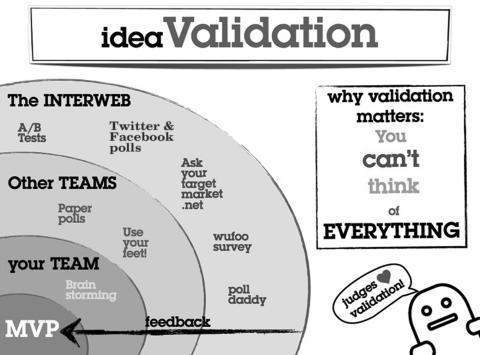

The reason to get out there and talk to people you don't know at an early stage is to confirm that there is an actual

need

for the product you want to create. This is called idea validation. While it's probably not possible at Startup Weekend to put the whole project on hold while you validate ideas, it would be useful if someone on the team at least attempted it. (Remember, you're already starting with some idea validation if other people have decided to join your team.

Someone

thinks it's a good idea.)

The goal of idea validation is not selling people on a product; it is to explore the field in order to gain knowledge, not money. Don't be offended by people who don't like your idea. Consider it knowledge gained. Now, you know the direction in which you should

not

take your product. You can be grateful that you've invested nothing but some time and energy in the project at this stage. You haven't created anything yet. And getting feedback now is usually easier for people. Think about it this way:

If you threw on a pair of pants and a shirt this morning and barely combed your hair, you would probably shrug it off if someone later made a snide remark about your appearance. (I didn't put much effort in making myself look presentable, so it's not surprising.) But if you went out, got a new haircut, a nice outfit, put on some makeup, and then someone didn't like your appearance, you'd be more upset. (I spent all this time and money and they still don't like the way I look.) While gaining this knowledge will not immediately lead to huge streams of revenue, it is vital to your company's success down the line.

Once you have created your minimum viable product, you can revisit these methods of getting feedback from potential customers to see if they like your product. Remember the basics: Ask people you don't know, and pose open-ended questions about the product. Don't be offended by the results. Just go back and see if you can incorporate the feedback you've gotten into the next version of the product. Try to formulate specific hypotheses about your product. To whom will it appeal? How many visitors do you expect to get at your website? It is important to be specific in order to see how well you are gauging your market.

Remember that old rule about the customer always being right? Well, there's a lot to it. Restaurant owners and people in the service industry are reminded of this concept on a daily basis. It doesn't matter if the guy said he wanted the coffee black and you gave it to him that way. Now he says he wants it with sugar. Don't argue with him; just give him the sugar. And smile. Or he won't come back tomorrow and he'll tell his friends not to as well. However, when you start making things that you're selling to customers who are not right in front of you, the

customer is always right

maxim often gets lost somewhere along the way. Since so many of the people who launched startups came from an engineering background, they were completely removed from the customer experience. The ideas behind customer development represent a revelation for many of them.

A lot of business books out there (for entrepreneurs and anyone else) emphasize

persistence

. The notion is that you should just keep trying your product, and talk about it in different ways. Keep working in your basement and eventually all that hard work will pay off. The bottom line, however, is that it may not. And if you talk to your customers early and often, you will find that out sooner rather than and later and free yourself to move on to an idea that will actually work.

Getting Lean, Staying Agile, Preparing to Pivot

As foundational as Steve Blank was to what has been an entrepreneurial revolution, he says that his theory of customer development is really only one piece of the new curriculum for entrepreneurs. Just as startups have to think about both their business models and marketing plans differently, they also have to think about how the organization operates and how to hire differently. In the years since Blank published his class notes in the form of a book called

Four Steps to the Epiphany

, others have begun to explore and explain these other pieces of the entrepreneur puzzle.

Sometimes they have developed theories and models from scratch. But other times, they have repurposed business theories from large, well-established companies. Toyota, for instance, had begun in the 1950s to use something called

lean

manufacturing to make cars more efficiently. The idea behind it was simply to create less waste. Companies that operate under the lean manufacturing approach try both to reduce waste and increase flow.

When you imagine an assembly line, you usually envision the processing of a large number of things. But lean manufacturing processes a very small amount of items at one time. Everything that is waiting to be produced is inventory, and you want the lowest inventory possible. For instance, it might take someone a short time to make a car door, and a long time to install it. Jeremy Lightsmith, a startup veteran who does consulting on lean strategies for large companies, explains it in the following way: “If you produce, produce, produce, and the thing that takes forever is attaching the door, and then you have all these doors that now you have to store, and if there's an error on the second door now you've made a hundred doors and they all have the same error.”

This idea may be even more important to small new businesses than large well-established ones. The small businesses don't have the extra manpower or the extra capital, so keeping inventory to a minimum is vital—and not just on the production line either. This is critical when developing a product as well. That's why entrepreneurs need to create only a minimum viable product and then test it with potential customers immediately. You don't want to create a whole lot of something unless you know customers are going to be happy with it. This approach allows you to take smaller risks.

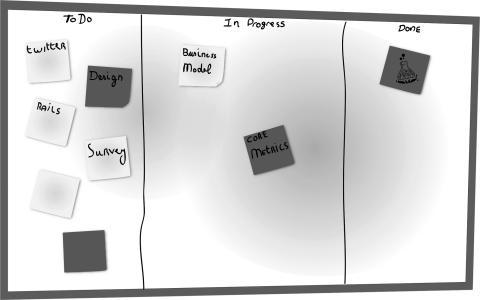

Software developers became particularly attuned to this problem in the 1990s, and began to work on a methodology that is now called

agile

development. Agile developers use a series of stories in order to make their products. Each of these stories then prompts another iteration of the product. For instance, let's say that you are using a website and want to log out so that the person who uses the computer after you doesn't get a hold of your credit card information. This requires a particular kind of functionality of the website. Solving that problem is a discrete task that can be done in a particular amount of time by a particular individual or group of individuals; it's a story. The time set aside to accomplish that task can be called a

sprint

. In this way, we can think of launching a new business as a series of sprints.

Over time,

agile

has become a type of shorthand for a certain method of project management. In the software realm, which is where people mostly use the term now, agile has come to include the ways in which people write codes and do their designs. The emphasis is on keeping these simple, so everyone on the team can understand them, and so they can be changed down the line without throwing everything off.

There are a variety of tools now available for entrepreneurs to use agile methods in their work. One of them is called

scrum

, which comes from the term for a huddle in the sport of rugby. New entrepreneurs and participants at Startup Weekend don't have to grasp all of the concepts behind the theory of scrum; however, we try to help Startup Weekend attendees pick out some tools they might find helpful during the course of the 54 hours they are with us.