Stone Fox

Authors: John Reynolds Gardiner

Stone Fox

Illustrated by Greg Hargreaves

To Bob at Hudson’s Café

1

• Grandfather

2

• Little Willy

3

• Searchlight

4

• The Reason

5

• The Way

6

• Stone Fox

7

• The Meeting

8

• The Day

9

• The Race

10

• The Finish Line

GRANDFATHER

O

NE DAY

G

RANDFATHER

wouldn’t get out of bed. He just lay there and stared at the ceiling and looked sad.

At first little Willy thought he was playing.

Little Willy lived with his grandfather on a small potato farm in Wyoming. It was hard work living on a potato farm, but it was also a lot of fun. Especially when Grandfather felt like playing.

Like the time Grandfather dressed up as the scarecrow out in the garden. It took little Willy an hour to catch on. Boy, did they laugh. Grandfather laughed so hard he cried. And when he cried his beard filled up with tears.

Grandfather always got up real early in the morning. So early that it was still dark outside. He would make a fire. Then he would make breakfast and call little Willy. “Hurry up or you’ll be eating with the chickens,” he would say. Then he would throw his head back and laugh.

Once little Willy went back to sleep. When he woke up, he found his plate out in the chicken coop. It was picked clean. He never slept late again after that.

That is…until this morning. For some reason Grandfather had forgotten to call him. That’s when little Willy discovered that Grandfather was still in bed. There could be only one explanation. Grandfather was playing. It was another trick.

Or was it?

“Get up, Grandfather,” little Willy said. “I don’t want to play anymore.”

But Grandfather didn’t answer.

Little Willy ran out of the house.

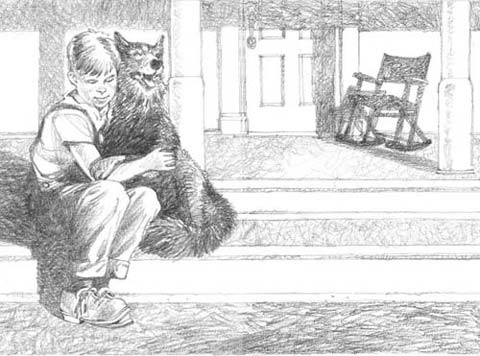

A dog was sleeping on the front porch. “Come on, Searchlight!” little Willy cried out. The dog jumped to its feet and together they ran off down the road.

Searchlight was a big black dog. She had a white spot on her forehead the size of a silver dollar. She was an old dog—actually born on the same day as little Willy, which was over ten years ago.

A mile down the road they came to a small log cabin surrounded by tall trees. Doc Smith was sitting in a rocking chair under one of the trees, reading a book.

“Doc Smith,” little Willy called out. He was out of breath. “Come quick.”

“What seems to be the matter, Willy?” the doctor asked, continuing to read.

Doc Smith had snow white hair and wore a long black dress. Her skin was tan and her face was covered with wrinkles.

“Grandfather won’t answer me,” little Willy said.

“Probably just another trick,” Doc Smith replied. “Nothing to worry about.”

“But he’s still in bed.”

Doc Smith turned a page and continued to read. “How late did you two stay up last night?”

“We went to bed early, real early. No singing or music or anything.”

Doc Smith stopped reading.

“Your grandfather went to bed without playing his harmonica?” she asked.

Little Willy nodded.

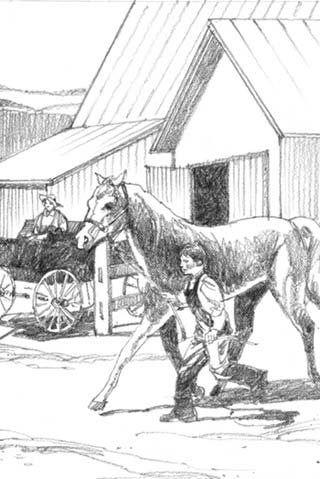

Doc Smith shut her book and stood up. “Hitch up Rex for me, Willy,” she said. “I’ll get my bag.”

Rex was Doc Smith’s horse. He was a handsome palomino. Little Willy hitched Rex to the wagon, and then they rode back to Grandfather’s farm. Searchlight ran on ahead, leading the way

and barking. Searchlight enjoyed a good run.

Grandfather was just the same. He hadn’t moved.

Searchlight put her big front paws up on the bed and rested her head on Grandfather’s chest. She licked his beard, which was full of tears.

Doc Smith proceeded to examine Grandfather. She used just about everything in her little black bag.

“What’s that for?” little Willy asked. “What are you doing now?”

“Must you ask so many questions?” Doc Smith said.

“Grandfather says it’s good to ask questions.”

Doc Smith pulled a long silver object from her doctor’s bag.

“What’s that for?” little Willy asked.

“Hush!”

“Yes, ma’am. I’m sorry.”

When Doc Smith had finished her examina

tion, she put everything back into her little black bag. Then she walked over to the window and looked out at the field of potatoes.

After a moment she asked, “How’s the crop this year, Willy?”

“Grandfather says it’s the best ever.”

Doc Smith rubbed her wrinkled face.

“What’s wrong with him?” little Willy asked.

“Do you owe anybody money?” she asked.

“No!” little Willy answered. “What’s wrong? Why won’t you tell me what’s wrong?”

“That’s just it,” she said. “There is

nothing

wrong with him.”

“You mean he’s not sick?”

“Medically, he’s as healthy as an ox. Could live to be a hundred if he wanted to.”

“I don’t understand,” little Willy said.

Doc Smith took a deep breath. And then she began, “It happens when a person gives up. Gives up on life. For whatever reason. Starts up

here in the mind first; then it spreads to the body. It’s a real sickness, all right. And there’s no cure except in the person’s own mind. I’m sorry, child, but it appears that your grandfather just doesn’t want to live anymore.”

Little Willy was silent for a long time before he spoke. “But what about…fishing…and the Rodeo…and turkey dinners? Doesn’t he want to do those things anymore?”

Grandfather shut his eyes and tears rolled down his cheeks and disappeared into his beard.

“I’m sure he does,” Doc Smith said, putting her arm around little Willy. “It must be something else.”

Little Willy stared at the floor. “I’ll find out. I’ll find out what’s wrong and make it better. You’ll see. I’ll make Grandfather want to live again.”

And Searchlight barked loudly.

LITTLE WILLY

A

TEN-YEAR-OLD BOY

cannot run a farm. But you can’t tell a ten-year-old boy that. Especially a boy like little Willy.

Grandfather grew potatoes, and that’s exactly what little Willy was going to do.

The harvest was just weeks away, and little Willy was sure that if the crop was a good one, Grandfather would get well. Hadn’t Grandfather been overly concerned about the crop this year? Hadn’t he insisted that every square inch of land be planted? Hadn’t he gotten up in the middle of the night to check the irrigation? “Gonna be our best ever, Willy,” he had said.

And he had said it over and over again.

Yes, after the harvest, everything would be all right. Little Willy was sure of it.

But Doc Smith wasn’t.

“He’s getting worse,” she said three weeks later. “It’s best to face these things, Willy. Your grandfather is going to die.”

“He’ll get better. You’ll see. Wait till after the harvest.”

Doc Smith shook her head. “I think you should consider letting Mrs. Peacock in town take care of him, like she does those other sickly folks. He’ll be in good hands until the end comes.” Doc Smith stepped up into the wagon. “You can come live with me until we make plans.” She looked at Searchlight. “I’m sure there’s a farmer in these parts who needs a good work dog.”

Searchlight growled, causing Doc Smith’s horse, Rex, to pull the wagon forward a few feet.

“Believe me, Willy, it’s better this way.”

“No!” shouted little Willy. “We’re a family, don’t you see? We gotta stick together!”

Searchlight barked loudly, causing the horse to rear up on his hind legs and then take off running. Doc Smith jammed her foot on the brake, but it didn’t do any good. The wagon disappeared down the road in a cloud of dust.

Little Willy and Searchlight looked at each other and then little Willy broke out laughing. Searchlight joined him by barking again.

Little Willy knelt down, took Searchlight by the ears, and looked directly into her eyes. She had the greenest eyes you’ve ever seen. “I won’t ever give you away. Ever. I promise.” He put his arms around the dog’s strong neck and held her tightly. “I love you, Searchlight.” And Searchlight understood, for she had heard those words many times before.

That evening little Willy made a discovery.

He was sitting at the foot of Grandfather’s

bed playing the harmonica. He wasn’t as good as Grandfather by a long shot, and whenever he missed a note Searchlight would put her head back and howl.

Once, when little Willy was way off key, Searchlight actually grabbed the harmonica in her mouth and ran out of the room with it.

“Do you want me to play some more?” little Willy asked Grandfather, knowing very well that Grandfather would not answer. Grandfather had not talked—not one word—for over three weeks.

But something happened that was almost like talking.

Grandfather put his hand down on the bed with his palm facing upward. Little Willy looked at the hand for a long time and then asked, in a whisper, “Does that mean ‘yes’?”

Grandfather closed his hand slowly, and then opened it again.

Little Willy rushed to the side of the bed. His eyes were wild with excitement. “What’s the sign for ‘no’?”

Grandfather turned his hand over and laid it flat on the bed. Palm down meant “no.” Palm up meant “yes.”

Before the night was over they had worked out other signals in their hand-and-finger code. One finger meant “I’m hungry.” Two fingers meant “water.” But most of the time little Willy just asked questions that Grandfather could answer either “yes” or “no.”

And Searchlight seemed to know what was going on, for she would lick Grandfather’s hand every time he made a sign.

The next day little Willy began to prepare for the harvest.

There was a lot of work to be done. The underground shed—where the potatoes would

be stored until they could be sold—had to be cleaned. The potato sacks had to be inspected, and mended if need be. The plow had to be sharpened. But most important, because Grandfather’s old mare had died last winter, a horse to pull the plow had to be located and rented.

It was going to be difficult to find a horse, because most farmers were not interested in overworking their animals—for any price.

Grandfather kept his money in a strongbox under the boards in the corner of his bedroom. Little Willy got the box out and opened it. It was empty! Except for some letters that little Willy didn’t bother to read.

There was no money to rent a horse.

No money for anything else, for that matter. Little Willy had had no idea they were broke. Everything they had needed since Grandfather

took sick little Willy had gotten at Lester’s General Store on credit against this year’s crop.

No wonder Grandfather was so concerned. No wonder he had gotten sick.

Little Willy had to think of something. And quick.

It was now the middle of September. The potatoes they had planted in early June took from ninety to one hundred twenty days to mature, which meant they must be harvested soon. Besides, the longer he waited, the more danger there was that an early freeze would destroy the crop. And little Willy was sure that if the crop died, Grandfather would die too.

A friend of Grandfather’s offered to help, but little Willy said no. “Don’t accept help unless you can pay for it,” Grandfather had always said. “Especially from friends.”

And then little Willy remembered something.

His college money! He had enough to rent

a horse, pay for help, everything. He told Grandfather about his plan, but Grandfather signaled “no.” Little Willy pleaded with him. But Grandfather just repeated “no, no, no!”

The situation appeared hopeless.

But little Willy was determined. He would dig up the potatoes by hand if he had to.

And then Searchlight solved the problem.

She walked over and stood in front of the plow. In her mouth was the harness she wore during the winter when she pulled the snow sled.

Little Willy shook his head. “Digging up a field is not the same as riding over snow,” he told her. But Searchlight just stood there and would not move. “You don’t have the strength, girl.” Little Willy tried to talk her out of it. But Searchlight had made up her mind.

The potato plant grows about two feet high, but there are no potatoes on it. The potatoes are

all underground. The plow digs up the plants and churns the potatoes to the surface, where they can be picked up and put into sacks.

It took little Willy and Searchlight over ten days to complete the harvest. But they made it! Either the dirt was softer than little Willy had thought, or Searchlight was stronger, because she actually seemed to enjoy herself.

And the harvest was a big one—close to two hundred bushels per acre. And each bushel weighed around sixty pounds.

Little Willy inspected the potatoes, threw out the bad ones, and put the rest into sacks. He then put the sacks into the underground shed.

Mr. Leeks, a tall man with a thin face, riding a horse that was also tall and had a thin face, came out to the farm and bought the potatoes. Last year Grandfather had sold the crop to Mr. Leeks, so that’s what little Willy did this year.

“We made it, Grandfather,” little Willy said, as tears of happiness rolled down his cheeks. “See?” Little Willy held up two handfuls of money. “You can stop worrying. You can get better now.”

Grandfather put his hand down on the bed. Palm down meant “no.” It was not the crop he’d been worried about. It was something else. Little Willy had been wrong all along.