Stonehenge a New Understanding (32 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

The unique, drum-shaped, small pottery object found with one of the cremation burials at Stonehenge and interpreted as an “incense burner.”

Beakers were used by communities across Europe, from Spain and Morocco to northern Denmark, and from Hungary to eastern Ireland.

20

They seem to have first appeared in Spain around 2800 BC, and there are also early dates from the Netherlands.

21

Their distribution across northern Europe, however, was patchy rather than uniform. Certain areas, such as much of France and southern Denmark, have never produced evidence for Beakers. In Britain, their footprint is similarly partial. Very few Beakers are known from Wales, for example, but certain areas such as eastern Scotland, Yorkshire, the Peak District, Wessex, East Anglia, and Kent were densely occupied by Beaker-using communities.

All of these areas are well-known for Beaker funerary sites, where the dead were buried either under round mounds or in flat burials with no earthen monument to mark them. It seems that the earliest burials, around 2400 BC, were placed in flat graves or within small circular, discontinuous ditches, like miniature henges.

22

Only later, around 2000 BC, were large earthen mounds—round barrows—built over a grave.

For years, archaeologists have argued about the Beaker people. Were they really a tribe or tribes of migrants sweeping across Europe, perhaps forced westward into the Netherlands and Britain by other groups expanding out of the east? Or were archery equipment and the distinctive Beaker itself—items so often found in burials—some of the trappings of a lifestyle that cut across ethnic boundaries, part of a package of material culture that was adopted enthusiastically by those aspiring to the Beaker way of life?

23

Arguments based on the shape of prehistoric skulls subsided many years ago. There is no way to tell if the apparent difference between the shapes of skulls found in long barrows (dating to around 3800–3400 BC) and skulls from burials dating to the beginning of the Beaker period (from 2400 BC) is the result of the invasion of Britain by a large number of people with a different genetic heritage. The long period between the long barrows and the Beaker burials—a time when very few people were buried and thus lacking in unburned human remains—makes it impossible to judge whether the preponderance of more rounded skulls is the result of gradual physiological change (known as genetic drift) in an existing population, or the result of a new migration.

24

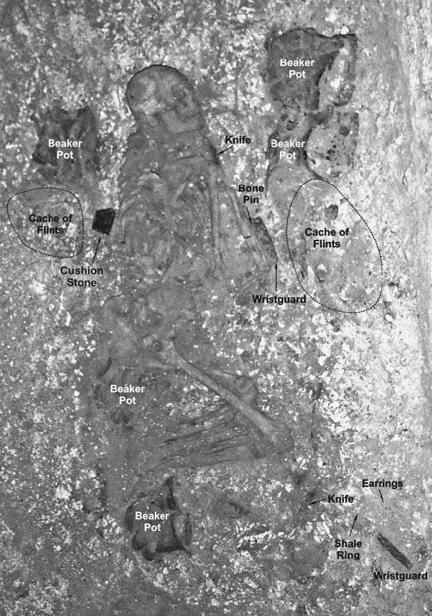

The arguments about migrants and the Beaker package had quieted down when a remarkable discovery was made in 2002 by Wessex Archaeology during the development of a new housing estate in Amesbury, just three miles east of Stonehenge on the other side of the Avon. The skeleton of an adult man lay in a grave with more than a hundred grave goods, including five Beakers, a dozen barbed-and-tanged arrowheads, three copper daggers, a boar’s tusk, a small stone anvil for fine metalworking, two gold “earrings” (perhaps twists for braided hair), and two wrist-guards.

25

This is the largest collection of grave goods ever found in a Beaker burial anywhere in Europe. The Amesbury Archer, or at least the people who organized his funeral, had considerable means and social standing. Nearby, a second flat grave contained the skeleton of another man, equipped with a pair of gold earrings.

The discovery of the Amesbury Archer couldn’t have happened at a more awkward time, late on a Friday before a holiday weekend. Andrew Fitzpatrick, in charge of the excavation, had to decide whether to leave the grave open to potential weekend plunderers or to dig through the night. He couldn’t take the risk of leaving the site so, working by the illumination of car headlights, his team pressed on for hours, patiently recording, plotting, and removing every single item on and around the skeleton.

Radiocarbon dating has revealed that the Amesbury Archer died in the period 2470–2280 BC. Analysis in the laboratory of his teeth tells a fascinating story: From the evidence of the strontium and oxygen isotope values of his molars’ dental enamel, we know that this man spent his childhood years (between the ages of about ten and fourteen) far away from Britain, somewhere on the Continent and possibly as far east as the foothills of the Alps.

26

Andrew Fitzpatrick suggested that the region around Bavaria might have been his homeland. The tabloids had a field day—Stonehenge built by the Germans! For a while, the Amesbury Archer was dubbed the King of Stonehenge, ousting the inhabitant of Bush Barrow from this ever-popular title. Some archaeologists wondered if he might have been the architect behind the building of the sarsen circle and trilithons, until it was pointed out that these had been erected before his time.

The Amesbury Archer and the artifacts buried with him as grave goods, excavated by Andrew Fitzpatrick of Wessex Archaeology.

The discovery of the Amesbury Archer reignited interest in the Beaker people’s origins. DNA was not going to help answer the question. There

are too few available skeletons from which ancient DNA could ever be extracted, and there are no skeletons from the centuries before the Beaker period to form a control group of “resident British citizens” with which to compare the DNA of the possible immigrants. The only way to find out if the Beaker people were migrants, or just local residents adopting new technology, is to analyze strontium and oxygen isotopes to see where people came from. Are there others like the Amesbury Archer, definitely immigrants from Europe?

In 2004, I put together a team of scientists to find out not just where the Beaker people had come from but also what their diet, their health, and their geographical mobility had been like. My codirectors were Andrew Chamberlain and Mike Richards. Andrew is an expert in biological anthropology, especially the study of human bones; Mike is an expert in isotope analysis. We recruited our team and talked to museums across Britain to track down Beaker skeletons. Our researchers identified over four hundred Beaker skeletons in various collections, but only 360 of them were suitable for our work. Children are too young for the isotope analyses on teeth to be worth doing, and we also had to exclude many of the elderly—sadly, the old folk didn’t have enough dental enamel left on the surfaces of their teeth.

Scientific projects in archaeology have none of the glamor and immediacy of discoveries made during excavations: Television documentary makers just don’t know how to make a good story out of people looking at computer printouts. The work is slow and it takes a very long time to obtain results from the various labs. Only six years after the beginning of this project on the Beaker people are we beginning to get enough results to be able to see the full picture. The diet in the Beaker period—as reconstructed from values of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the bones—was surprisingly uniform from Scotland to Kent.

27

No one was eating marine fish or seafood in detectable quantities, even though lots of the burials analyzed were from coastal areas of Scotland, Yorkshire, and Kent. Animal protein—either as meat, milk, or blood—was a central part of the diet but not massively predominant.

The wear marks visible microscopically on the Beaker people’s teeth can also tell us about their food.

28

These marks are minute scratches and pits on the teeth’s grinding surfaces that are constantly being erased and

renewed, and show what a dead person’s diet was like in the last few months of life. Interestingly, the Beaker teeth show no sign of the characteristic wear marks caused by eating stone-ground flour. Plenty have microscopic pitting of the sort most likely to be caused by the tiny grits that lurk inside green vegetables when they’re not thoroughly washed. Finally, Lucija Šoberl’s separate study of the lipids, or fatty acids, in the Beaker pots shows that these mostly contained dairy products—whether milk, cheese, or curds and whey, we cannot say.

29

Like the results so far from the Aubrey Hole bones, the Beaker skeletons have revealed that most individuals led lives of good health. Only a handful, like the Stonehenge Archer, buried in the ditch with arrow wounds all over his body, died violently. In fact, the number of woundings that have left traces on the body is far greater among the burials in the Early Neolithic long barrows, more than a thousand years earlier than the Beaker burials.

30

The low level of violent injury on Beaker-period bones belies the archer’s equipment frequently found in Beaker graves. One man in eastern Scotland had had his arm broken from being sharply twisted, but it had healed long before he died. Arthritis was common at a low level, like the cases seen on some of the Aubrey Hole remains. There was no evidence for malnutrition; had there been episodes of famine, these would have shown up as enamel hypoplasia, ridges in the teeth relating to periods of starvation in an individual’s life.

31

One of the completely unexpected discoveries was that a small number—fewer than half a dozen—of the Beaker skulls show evidence of head-binding during childhood. The human head can be easily distorted into a chosen, socially preferred shape by wrapping an infant’s skull very tightly to constrain its growth. Archaeologists are familiar with this practice elsewhere (it occurred frequently among the ancient Maya and the Huns, for example), but it has rarely been documented for prehistoric Britain.

The answers to questions about mobility and migration are to be found in the isotope levels within people’s tooth enamel. As well as using strontium and oxygen isotopes, the project also developed the study of sulphur isotopes. The value in the human body of sulphur isotopes varies with exposure to sea spray: The further inland people live, the lower the

value. Using this technique we hoped to see if people buried inland had ever lived nearer the sea. Overall, the isotope results show that about half the Beaker people studied grew up in an area different to that in which they were buried. Fewer than seven people from Britain (including the Amesbury Archer) had isotope values indicating that they could have grown up outside Britain. This was not a population that had moved lock, stock, and barrel from mainland Europe, nor are we looking at a population of completely sedentary farmers, growing up to marry the boy next door and never leaving their home village.

It was slightly disappointing to discover how few of these Beaker people were likely to have been immigrants to Britain. For the Amesbury Archer, it is his unusual oxygen isotope value that shows he is likely to have grown up on the Continent. Unfortunately, anyone growing up on the Continent within a couple of hundred miles or so of the English Channel would have an oxygen isotope value no different from someone growing up on the British side. Two burials from Kent may well be those of immigrants, because their dietary isotope values are different from others in Britain, but we cannot be certain that they were incomers. Three burials from the Peak District have strontium isotope values higher than expected for Britain. Quite possibly these could also be immigrants.

When we think about migrations, we often envisage successive waves of incomers whose second, third, and successive generations would have been born on British soil but continued the traditions of their immigrant ancestors. The results of this project suggest that a small number of immigrants from Europe arrived in Britain at the beginning of this new cultural phase, around 2400 BC, but that they were not followed by a series of subsequent migrations over the next five centuries. The Amesbury Archer is perhaps a “founder” burial from that initial phase of migration. These arrivals might well have been very few in number, in contrast to their many descendants born in Britain. Equally, many of indigenous British ancestry would have adopted Beaker fashions of lifestyle and burial rites. There is certainly very little evidence for successive waves of immigrants during the Beaker period, except for the small group that ended up in the Peak District a century or two after the initial Beaker arrival, having left a homeland (as yet unidentified) very different from that of the Amesbury Archer.