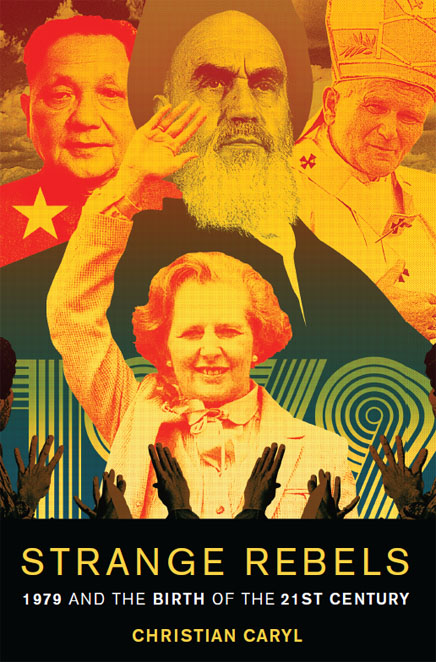

Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century

Read Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century Online

Authors: Christian Caryl

Tags: #History, #Revolutionary, #Modern, #20th Century, #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #World, #Political Ideologies

Strange Rebels

STRANGE REBELS

1979 AND THE BIRTH OF THE 21

ST

CENTURY

CHRISTIAN CARYL

BASIC BOOKS

A MEMBER OF THE PERSEUS BOOKS GROUP

New York

Copyright © 2013 by Christian Caryl

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

Designed by Timm Bryson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Caryl, Christian.

Strange rebels : 1979 and the birth of the 21st century / Christian Caryl.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-03335-5 (e-book) 1. History, Modern—1945–1989. 2. World politics—1975–1985. I. Title.

D849.C374 2013

909.82′7—dc23

2012048264

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memoriam: Leonard Caryl, Joan Greene,

and Henry Greene—the best parents a boy could have

3

“A Wild but Welcoming State of Anarchy”

4

The Emperor as Revolutionary

13

Thrice Banished, Thrice Restored

23

“The Lady’s Not for Turning”

24

Socialism with Chinese Characteristics

Epilogue: The Problem with Progress

History has a way of playing tricks. As events unfold around us, we interpret what we see through the prism of precedent, and then are amazed when it turns out that our actions never play out the same way twice. We speak confidently about “the lessons of the past” as if the messy cosmos of human affairs could be reduced to the order of a classroom.

Rarely has the past proven a more deceptive guide to the future than at the end of the eighth decade of the twentieth century. If you take a certain pleasure in seeing the experts confounded and the pundits dismayed, then 1979 is sure to hold your interest.

In January of that year, the shah of Iran got on a plane and left his country, never to return. He had been on the throne for thirty-seven years. He was toppled by a wave of rebellion that brought millions of protesters onto the streets of Iranian cities. The crowds they formed were some of the biggest humankind has ever witnessed, before or since. Yet just a few years earlier, well-informed observers had been hailing Iran as a miracle of modernization and praising the shah for the brilliance of his economic reforms. His hold over Iranian society was deemed unshakable; after all, he presided over one of the world’s biggest armies, not to mention a brutally effective secret police. But now his subjects were taking to the streets, declaring their eagerness to die for the cause of an elderly Shiite legal scholar living in Parisian exile.

Most outsiders couldn’t fathom what was happening in Iran. Decades earlier the German philosopher Hannah Arendt had assured her readers that revolutions—France in 1789, Russia in 1917—were, by definition, the products of secular modernizers. So what was one to make of the Iranian masses chanting religious slogans?

Surely, the very phrase

Islamic Revolution

was a contradiction in terms. Many Westerners and Iranians alike responded by denying the phenomenon altogether, concluding that it was all a smoke screen for a “real” revolution engineered by the forces of the Left, who had to be using religion to camouflage their real intentions. Others compared Khomeini to Gandhi, another leader who had employed the rhetoric of faith in an anti-imperialist struggle. Events soon demonstrated just how misplaced this analogy was.

Jimmy Carter, who was US president at the time, had a simpler analysis. Khomeini, according to him, was simply “crazy.”

1

This was a view that, in its sheer desperation, speaks volumes about the difficulties facing outsiders who were struggling to comprehend the events in Iran. Khomeini was not insane (though he might have been willing to assert that he was sometimes “drunk with the presence of God,” since he was a man steeped in Sufi poetic traditions). He was, in fact, a shrewd and methodical man who, in his approach to politics, repeatedly displayed a sharp sense of pragmatism.

Khomeini was no improviser. He had spent years shaping his vision of a future Iran, one in which Shia clerics would run the government and exercise supervision over virtually every aspect of society. But the road to that goal turned out to be a complicated one. Although the Quran offers a comprehensive ethical and political blueprint for society, it offers little practical detail on the ins and outs of administering a modern nation-state. For all its philosophical and poetic richness, the Holy Book of Islam has little to say about the specifics of monetary policy, exchange rates, or agricultural subsidies. So the course of the Iranian revolution ricocheted through abstruse scriptural debates, outbursts of violence, and the constraints of the possible—a history that bequeathed to the new Islamic Republic a range of eccentric political arrangements that make it a strikingly unpredictable place to this day. It should come as little wonder that Khomeini found the path to be so tortuous. In this respect, the “Islamic Revolution” was untraveled territory not only to outsiders, but also to its founders.

The upheaval in Iran had an explosive effect on the rest of the Islamic world. This was most apparent in Afghanistan, its neighbor to the east. Here, too, the decision makers in both Washington and Moscow initially overlooked the impact of religion. When the doddering Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and his Politburo colleagues decided to send their troops across the border on Christmas Day 1979 to quash a revolt against the country’s recently installed communist regime, Western observers instinctively recalled earlier episodes of the Cold War. Moscow’s grab for Kabul, they said, was simply a repetition of earlier interventions in Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968, when Russian tanks had crushed local

anti-Communist rebellions. The powers that be in Washington immediately assumed that the Russians were seizing an opportunity to make an aggressive thrust toward the strategically vital Persian Gulf. The old men in the Kremlin actually had more modest motives: they were desperate to shore up the crumbling twenty-month-old Communist regime, which had succeeded in the course of its brief life in alienating just about everyone in the country. The KGB even suspected the Afghan Communist leader, Moscow’s own client, of hatching covert plans to court the West.

But both Washington and Moscow failed to predict the forces that the invasion would unleash. Here, too, the insurgent power of revivalist Islam took observers by surprise. Some commentators, recalling Afghanistan’s history of resistance to foreign invaders, speculated that fanatical Muslims would prove a match for the Russians. But what loomed in their minds was the image of the romantic tribal fighters who had given the British Empire such difficulties in the nineteenth century. What no one foresaw was how the odd fusion of Islam and late-twentieth-century revolutionary politics—a formula whose mostly Sunni version in Afghanistan had much in common with the fervor stirred up by Khomeini’s Shiite followers—would combust into a strange new kind of global religious conflict. It is true that the Afghan revolt against Communist rule initially took the form of a traditional tribal uprising. But events soon demonstrated the power of the odd new phenomenon known as “Islamism.” Within the space of just a few years, this religious insurgency would supplant Marxism and secular nationalism as the dominant opposition ideology of the Middle East.

This revivalist spirit was not restricted to the world of Islam. There were Westerners, too, who believed that it was time for religion to reassert itself against the onslaught of secularization. In October 1978, the College of Cardinals that had come together in Rome to elect a pope had jolted the world by settling upon a Pole, Karol Wojtyła, the archbishop of Kraków. The new pontiff, who chose the name “John Paul II,” was a virtual unknown even to the faithful in St. Peter’s Square who had assembled to hear the outcome of the election. News commentators and Vatican officials mispronounced his name. Their confusion was understandable. He was the first non-Italian to become bishop of Rome since the Dutchman Adrian VI was chosen for the job 457 years earlier.

But it was the politics of the Cold War that really made Wojtyła’s selection momentous. As a priest who came from behind the Iron Curtain, he had spent his entire career confronting the political and spiritual challenge of Communism. Just seven months after his election, in June 1979, the new pope proceeded to demonstrate his transformative potential by embarking on a pastoral visit to his Polish

homeland that shook Communist rule in East Central Europe to its very foundations. Here, too, it would take time for all the ramifications of this event to reveal themselves—perhaps because no one suspected that it would catalyze a campaign of nonviolent moral and cultural resistance to a twentieth-century totalitarian regime. For all his determination to undermine Marxism-Leninism, the pope himself could not foresee how his efforts would hasten the collapse of the Soviet empire within his own lifetime. “On being elected pope, John Paul II did not believe that the day was close at hand when communism would lose,” as George Weigel, his most sympathetic biographer, notes.

2

Margaret Thatcher’s election as British prime minister in May 1979 marked another radical caesura. It wasn’t just that she was the first woman to hold the nation’s highest elected office; her significance went far beyond the mundane fact of her gender. If the pope and the Islamists stood for the rising assertiveness of religion, the ascendancy of Thatcher signaled a new shift with equally profound global implications: she was a missionary of markets, zealously determined to dismantle socialism and restore the values of entrepreneurship and self-reliance among her compatriots.

3

At the beginning of her term in office, her views on economic policy were so unconventional that they made her part of the minority within her own cabinet. Indeed, it was Thatcher’s battles with her fellow Conservatives, as much as with her opponents on the Left, that shaped the free-market agenda that would soon alter her country and the world.