Stripping Down Science (18 page)

Read Stripping Down Science Online

Authors: Chris Smith,Dr Christorpher Smith

In 1968, the Bee Gees penned a set of lyrics which included the lines âIt's only words, and words are all I have â¦' The result was a hit for them and also for the parade of artists who have since covered and re-covered that very song, âWords'. At the same time, many of us would probably agree that words, used the right way, can be pretty powerful.

As it turns out, the Bee Gees actually missed a trick, because new research has revealed that there's far more to a touching oratory than just the sounds we hear. In fact, a study from Canada shows that we genuinely do feel âmoved' by speech, because the brain picks up the sensations of air rushing past the body and uses this to bolster its understanding of what's being said.

For English speakers, this mostly applies to sounds like âpa' and âta', produced by placing the tongue towards the front of the mouth. Critically, these sounds are also accompanied by a puff of

air as you make them, noticeable if a hand is held in front of the lips as the letters are articulated. In isolation they're quite easy to make out, but throw in a cocktail party or a live band in the background and these âpa' and âta' noises can be quite hard to discriminate from the similar sounds âda' and âba' â except that these latter sounds aren't associated with any significant rush of air when you say them.

This got Bryan Gick and Donald Derrick, two researchers who are based at the University of British Columbia,

59

wondering whether the brain might make use of these effects as the aerodynamic equivalents of lip-reading. To find out, they rigged up a sound experiment in which 66 blindfolded volunteers listened through headphones to recordings of a male voice saying âpa', âta', âda' and âba' sounds. The subjects were asked to indicate, by pressing buttons, which sounds they had heard. At the same time as the sounds were being played, on some occasions the researchers also squirted brief pulses of air from a tube onto one of the subjects' hands or their necks.

When presented alongside âpa' and âta' sounds, which are naturally accompanied by an air-rush, the puffs of air from the tube significantly boosted the accuracy of the subjects' hearing. They went from being right about 65% of the time to being right more than 75% of the time.

That was when the air puffs accompanied the sounds they should have done. But what would happen if a subject experienced an air puff when they heard a âba' or âda' sound that would not normally be associated with any such gaseous emission? Incredibly, by playing this trick, the researchers found they could fool the brains of the subjects into hearing the wrong thing. Their accuracy fell from 85% in the absence of any air puffs to about 70%. Another surprise was that it didn't seem to matter which part of the body the air puff was hitting â hand or neck, both had the same effect. As Bryan Gick puts it, âIt sort of challenges this traditional idea that you see with your eyes and that gets processed by a particular part of your brain and you hear with your ears and that gets processed by another part of your brain. It looks like our brains just take everything in.'

In other words, it seems that in making sense of what's being said, the brain takes its lead

partly from the Bee Gees and also injects a dose of a-ha's âTouch Me'. It certainly adds a whole new dimension to the phrase âbreathing down someone's neck' â¦

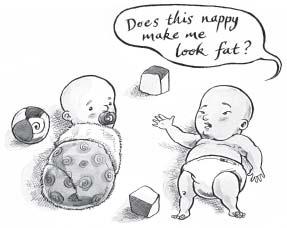

Anyone who's ever spent time with a toddler knows only too well how many words they've already mastered. New linguistic gymnastics appear on an almost daily basis, most of it mimicked from mum and dad. Indeed, by the time the average English speaker reaches the age of 17, they probably know more than 60,000 words. But what about their accent?

The way we sound singles us out almost as distinctively and uniquely as the way we look, but where did we learn to speak like that and why? At the simplest level, accents are just the way we choose to make the sounds that others

comprehend as language. And because humans are social creatures that strive to bond and to imitate one another, which is â after all â how we learn, scientists had thought that accents were something we acquired as language developed.

But new research shows that this is a tongue-twistingly massive myth, because â

Ooh, la la

â scientists in France and Germany have now found that babies are born with their accents already in place. Kathleen Wermke, a behavioural scientist at the University of Würzburg,

60

made the discovery when she and her colleagues recorded the cries of 60 French and German newborns, all of whom were under three days old. They fed the coos and yelps into a computer program that analysed the frequency and melody contours of the cries.

In each case, a characteristic âsignature spectrum' emerged, which strongly correlated with the nationality of the newborn. Those with French mothers produced a rising melody contour, while German babies had a falling melody contour. In other words, the cries either increased or decreased in pitch with time. Astonishingly, these contours matched the sonic signatures of the parents' native languages.

How were the babies picking up their accent in the first place? The simple answer is by eavesdropping on mum's conversations. We know that sounds made by a pregnant mother, as well as speech and other noises originating from outside the body, can make it into the uterus to be picked up by a baby. This was confirmed in 2004, with the help of a pregnant sheep, by two researchers at the University of Florida, Ken Gerhardt and Robert Abrams.

61

They placed a tiny microphone inside the ear canal of a developing lamb. Then, 64 spoken sentences were played on a loudspeaker placed in the open air next to the pregnant sheep while a recording was made simultaneously from the microphone in the lamb's ear. When the lamb-ear recordings were then played back to a group of 30 human volunteers, more than 30% of what was said could be understood. Critically, however, the recordings revealed that the low-frequency sounds were picked up best. According to Gerhardt, in the context of what might be transmitted to a developing human baby, âThat means they are more sensitive to the melodic parts of speech than

to pitch.' So far, so good. But does a developing human baby really âhear'

in utero

?

âYes,' say scientists, who think that the hearing system is probably wired up and working by 30 weeks gestation. Barbara Kisilevsky, from Queen's University in Canada,

62

played sounds to 143 foetuses aged between 23 and 34 weeks of gestation while watching their reactions

in utero

using ultrasound. Babies aged over 30 weeks, she found reacted to the sounds, but the less-developed individuals didn't.

It seems, therefore, that developing babies can hear what mum's nattering about. But why bother copying her? Subversion on the part of the baby, suggests Kathleen Wermke. To make sure its mother loves it. âNewborns are probably highly motivated to imitate their mother's behaviour,' she says, âin order to attract her and hence to foster bonding.'

So why do it in cries? you ask. âBecause,' she points out, âmelody contour may be the only aspect of their mother's speech that newborns are able to imitate; this may explain why we found melody contour imitation at that early age.' So

watch out: not only is your future son or daughter listening intently to everything you say towards the end of pregnancy, they're also learning to take you off!

FACT BOX

Nature vs. nurture?

Apart from accents, there are many other things that babies pick up from their parents, or appear to. But a big problem in biology is how to disentangle the effects of inherited genes â in other words,

nature

â from the effects of the local environment in which the child grows up â that is,

nurture

.

For instance, scientists have noticed a link between maternal smoking and babies born with a low birthweight, and there is also an increased likelihood that a smoker's child will display antisocial behaviour when it grows up. But to what extent might genes be responsible for both of these effects and, conversely, how much of a role does the environment play?

Mothers who smoke when they are pregnant might be more likely to have behavioural problems themselves or a genetic tendency to deliver low birthweight babies that also makes them smoke.

Anita Thapar, a researcher at Cardiff University in Wales,

63

recently came up with an ingenious way to solve this problem. She compared maternal smoking with the birthweights and subsequent antisocial behaviour rates amongst 779 children. But these weren't any old children: these study subjects were all conceived by

in-vitro

fertilisation (IVF) and over 200 of the babies were born from

donor

eggs. In other words, the babies born from these eggs were genetically unrelated to their âmothers' but still developed exposed to the environment inside her. This neat study design meant that, in assessing the outcomes for the children, genetic factors â

nature

â could be effectively separated from

nurture

effects â maternal and environmental factors.

What emerged from the analysis was a very

strong relationship between maternal smoking and low birthweight in both children who were genetically related to their mothers and the genetically unrelated children born from donor eggs. This proves that the effect of smoking on birthweight is not down to genetics, but must be due to the toxic effect of smoking itself.

Antisocial behaviour, on the other hand, was only associated with maternal smoking in children who were genetically related to their mothers; there was no statistical association amongst the children born using donor eggs. In other words, a genetic tendency present in the child and passed down from the mother is triggering the antisocial behaviour. This same genetic tendency may also explain why mum smoked while she was pregnant in the first place.

âThis shows the importance of inherited factors in the association between prenatal smoking and offspring behaviour,' says Thapar. âThis suggests that gene-environment correlation is important in explaining this association.'