Stuka Pilot (33 page)

Authors: Hans-Ulrich Rudel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #World War II, #War & Military

So disregarding the order I concentrate my attacks on genuine targets on either bank: tanks, vehicles and artillery. One day a general sent from Berlin turns up and tells me that reconnaissance photographs always show new bridges.

“But,” he says, “you do not report that these bridges have been destroyed. You must keep on attacking them.”

“By and large,” I explain to him, “they are not bridges at all,” and when I see him contort his face into a question mark an idea occurs to me. I tell him that I am just about to take off, I invite him to sit behind me and promise to give him practical proof of this. He hesitates for a moment, then observing the curious glances of my junior officers who have heard my proposition with some glee, he agrees. I have given the unit a standing order to attack the bridgehead, I myself approach the objective at the same low level and fly from Schwedt to Frankfurt-on-the-Oder. At some points we encounter quite respectable flak and the general soon admits that he has now seen for himself that the bridges are in fact tracks. He has seen enough. After landing he is as pleased as Punch that he has been able to convince himself and can make his report accordingly. We are quit of our daily bridge chore. One night Minister Speer brings me a new assignment from the Führer. I am to formulate a plan for its execution. Briefly, he tells me:

“The Führer is planning attacks on the dams of the armament industry in. the Urals. He expects to disrupt the enemy’s arms production, especially of tanks, for a year. This year will then give us the chance of exploiting the respite decisively. You are to organize the operation, but you are not to fly yourself, the Führer repeated this expressly.”

I point out to the minister that there must surely be some one better qualified for this task, namely in Long Distance Bomber Command, who will be far more conversant with such things as astronomical navigation, etc. than I am who have been trained in dive-bombing and therefore have quite a different kind of knowledge and experience. Furthermore, I must be allowed to fly myself if I am to have an untroubled mind when briefing my crews.

“The Führer wishes you to do it,” objects Speer.

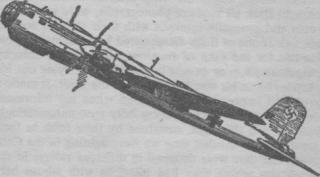

I raise some fundamental technical questions regarding the type of aircraft and the kind of bombs with which this operation is to be carried out. If it is to be done soon only the Heinkel 177 comes into consideration, though it is not absolutely certain that it will prove suitable for this purpose. The only possible bomb for such a target is, in my opinion, a sort of torpedo, but that too has yet to be tested. I flatly refuse to listen to his suggestion to use 2000 lb. bombs; I am positive that no success can be achieved with them. I show the Minister photographs taken in the Northern sector of the Eastern Front where I dropped two thousand pounders on the concrete pillars of the Neva bridge and it did not collapse. This problem must therefore be resolved and also the question of my being allowed to accompany the mission. These are my stipulations should the Führer insist on my undertaking the task. He already knows my objections that my practical experience is confined to a totally different field.

He. 177

Now I take up the file of photographs of the factories in question and study them with interest. I see that a high percentage of them are already underground and are therefore partly unassailable from the air. The photographs show the dam and the power station and some of the factory buildings; they have been taken during the war. How can this have been done? I think back to my time in the Crimea and put two and two together. When I was stationed at Sarabus and keeping myself fit by a little putting the weight and discus throwing after operations a black-painted aircraft often used to land on the airfield, and very mysteriously passengers alighted. One day one of the crew told me under the seal of secrecy what was going on. This air craft carried Russian priests from the freedom-loving states of the Caucasus who volunteered for important missions for the German command. With flowing beards and dressed in clerical garb each of them carried a little packet on his chest, either a camera or explosives according to the nature of his mission. These priests regarded a German victory as the only chance of regaining their independence and with it their religious liberty. They were fanatical enemies of world Bolshevism and consequently our allies. I can still see them: often men with snow white hair and noble features as if chiseled out of wood. From the deep interior of Russia they brought back all kinds of photographs, were months en route and generally returned with their mission accomplished. If one of them disappeared he presumably gave his life for the sake of freedom, either in an unlucky parachute jump or caught in the act of carrying out his purpose or on his way back through the front. It made a profound impression on my mind when my informant described to me the way these holy men unhesitatingly jumped into the night, sustained by their faith in their great mission. At that time we were fighting in the Caucasus and they were dropped in different valleys in the mountains where they had relations with whose help they proceeded to organize resistance and sabotage.

It all comes back to me as I puzzle over the origin of the photographs of these industrial plants.

After some general remarks on the present state of the war, in which Speer expresses his complete confidence in the Führer, he leaves in the small hours of the morning, promising to send me further details about the Urals plan. It never got as far as that, for a few days later the ninth of February made everything impossible.

So the task of working out this plan devolved upon somebody else. But then in the rush of events to the end of the war its execution was to be no longer practical.

17. THE DEATH STRUGGLE OF THE LAST MONTHS

E

arly on the morning of the 9th February a telephone call from H.Q.: Frankfurt has just reported that last night the Russians bridged the Oder at Lebus, slightly north of Frankfurt and with some tanks have already gained a footing on the west bank. The situation is more than critical; at this point there is no opposition on the ground and there is no possibility of bringing up heavy artillery there in time to stop them. So there is nothing to prevent the Soviet tanks from rolling on towards the capital, or at least straddling the railway and the autobahn from Frankfurt to Berlin, both vital supply lines for the establishment of the Oder front.

We fly there to find out what truth there is in this report. From afar I can already make out the pontoon bridge, we encounter intense flak a long way before we reach it. The Russians certainly have a rod in pickle for us! One of my squadrons attacks the bridge across the ice. We have no great illusions about the results we shall achieve, knowing as we do that Ivan has such quantities of bridge-building material that he can repair the damage in less than no time. I myself fly lower with the anti-tank flight on the look-out for tanks on the west bank of the river. I can discern their tracks but not the monsters themselves. Or are these the tracks of A.A. tractors? I come down lower to make sure and see, well camouflaged in the folds of the river valley, some tanks on the northern edge of the village of Lebus.

There are perhaps a dozen or fifteen of them. Then something smacks against my wing, a hit by light flak. I keep low, guns are flashing all over the place, at a guess six or eight batteries are protecting the river crossing. The flak gunners appear to be old hands at the game with long Stuka experience behind them. They are not using tracers, one sees no string of beads snaking up at one, but one only realizes that they have opened up when the aircraft shudders harshly under the impact of a hit. They stop firing as soon as we climb and so our bombers cannot attack them. Only when one is flying very low above our objective can one see the spurt of flame from the muzzle of a gun like the flash of a pocket torch. I consider what to do; there is no chance of coming in cunningly behind cover as the flat river valley offers no opportunities for such tactics. There are no tall trees or buildings. Sober reflection tells me that experience and tactical skill go by the board if one breaks all the fundamental rules derived from them. The answer: a stubborn attack and trust to luck. If I had always been so foolhardy I should have been in my grave a dozen times. There are no troops here on the ground and we are fifty miles from the capital of the Reich, a perilously short distance when the enemy’s armor is already pushing towards it. There is no time for ripe consideration. This time you will have to trust to luck, I tell myself, and in I go. I tell the other pilots to stay up; there are several new crews among them and while they cannot be expected to do much damage with this defense we are likely to suffer heavier losses than the game is worth. When I come in low and as soon as they see the flash of the A.A. guns they are to concentrate their cannon fire on the flak. There is always the chance that this will get Ivan rattled and affect his accuracy. There are several Stalin tanks there, the rest are T 34s. After four have been set on fire and I have run out of ammunition we fly back. I report my observations and stress the fact that I have only attacked because we are fighting fifty miles from Berlin, otherwise it would be inexcusable. If we were holding a line further east I should have waited for a more favorable situation, or at least until the tanks had driven out of range of their flak screen round the bridge. I change aircraft after two sorties because they have been hit by flak. Back a fourth time and a total of twelve tanks are ablaze. I am buzzing a Stalin tank which is emitting smoke but refuses to catch fire.

Each time before coming in to the attack I climb to 2400 feet as the flak cannot follow me to this altitude. From 2400 feet I scream down in a steep dive, weaving violently. When I am close to the tank I straighten up for an instant to fire, and then streak away low above the tank with the same evasive tactics until I reach a point where I can begin to climb again—out of range of the flak. I really ought to come in slowly and with my aircraft better controlled, but this would be suicide. I am only able to straighten up for the fraction of a second and hit the tank accurately in its vulnerable parts thanks to my manifold experience and somnambulistic assurance. Such attacks are, of course, out of the question for my colleagues for the simple reason that they have not the experience.

The pulses throb in my temples. I know that I am playing cat and mouse with fate, but this Stalin tank has got to be set alight. Up to 2400 feet once more and on to the sixty ton leviathan. It still refuses to bum! Rage seizes me; it must and shall catch fire!

The red light indicator on my cannon winks. That too! On one side the breech has jammed, the other cannon has therefore only one round left. I climb again. Is it not madness to risk everything again for the sake of a single shot? Don’t argue; how often have you put paid to a tank with a single shot?

It takes a long time to gain 2400 feet with a Ju. 87; far too long, for now I begin to weigh the pros and cons. My one ego says: if the thirteenth tank has not yet caught fire you needn’t imagine you can do the trick with one more shot. Fly home and remunition, you will find it again all right. To this my other ego heatedly replies:

“Perhaps it requires just this one shot to stop the tank from rolling on through Germany.”

“Rolling on through Germany sounds much too melodramatic! A lot more Russian tanks are going to roll on through Germany if you bungle it now, and you will bungle it, you may depend upon that. It is madness to go down again to that level for the sake of a single shot. Sheer lunacy!”

“You will say neat that I shall bungle it because it is the thirteenth. Superstitious nonsense You have one round left, so stop shilly-shallying and get cracking!”

And already I zoom down from 2400 feet. Keep your mind on your flying, twist and turn; again a score of guns spit fire at me. Now I straighten up… fire… the tank bursts into a blaze! With jubilation in my heart, I streak away low above the burning tank. I go into a climbing spiral… a crack in the engine and something sears through my leg like a strip of red hot steel. Everything goes black before my eyes, I gasp for breath. But I must keep flying… flying… I must not pass out. Grit your teeth, you have to master your weakness. A spasm of pain shoots through my whole body.

“Ernst, my right leg is gone.”

“No, your leg won’t be gone. If it were you wouldn’t be able to speak. But the left wing is on fire. You’ll have to come down, we’ve been hit twice by 4 cm. flak.”

An appalling darkness veils my eyes, I can no longer make out anything.

“Tell me where I can crash-land. Then get me out quickly so that I am not burnt alive.”

I cannot see a thing any more, I pilot by instinct. I remember vaguely that I came in to each attack from south to north and banked left as I flew out. I must therefore be headed west and in the right direction for home. So I fly on for several minutes. Why the wing is not already gone I do not know. Actually I am moving north north west almost parallel to the Russian front. “Pull!” shouts Gadermann through the intercom, and now I feel that I am slowly dozing off into a kind of fog… a pleasant coma.