Sun on Fire (27 page)

Authors: Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedural, #International Mystery & Crime, #Thrillers, #Crime

“You sure?”

“More or less. See how it is in the morning. I’ll be in if I’m not feeling any worse. What’s happening at the station?”

“The police chief set up a special team—with him heading it—to supervise the search. We’re supposed to work with them.”

22:30

This was a long day for Anna. She often made life more difficult for herself through her reluctance to delegate when in the thick of things. She trusted no one. In a crime-scene investigation, she preferred to deal with all the menial tasks herself. That could mean working well into the night, and now Birkir had added this notepad to her workload.

She began by removing the top leaf from the pad and examining it in different types of light. When that brought no useful results, she went out to the parking lot for a break to consider the best approach to what was an unusual challenge for her.

After some fresh air and two cigarettes, she felt clear on how to proceed. She went to the equipment room and got a bag that contained a small metal box—an Electrostatic Detection Device, or EDD. She set the device on her workbench and switched it on. A fan started up, creating suction through the perforated top platen, which gripped the sheet of paper when she put it in place. She then covered the paper with a very thin Mylar film, over which she waved the attached electrostatic wand for several seconds to create a positive charge in the paper.

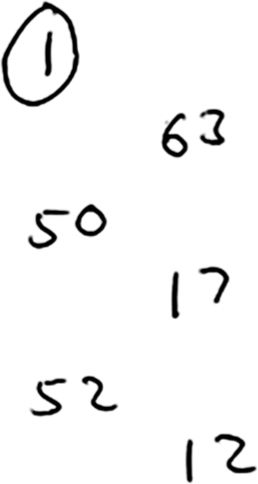

Another part of the kit was black toner powder, and she now carefully scattered some of this over the film’s surface. She knew the theory: The pressure of the pen used to write on a notepad causes the filaments of the paper below to break—and waving an electromagnetic field over the paper imparts a positive charge to the ends of those broken filaments, which attracts the negatively charged toner. But still it was like magic when the powder Anna

dusted over the plastic film created a vivid copy of the last thing that had been written on the pad. Underneath, she could see a fainter image of an older message, probably a household shopping list for Jónshús.

What Anna read was not an address—just a few rows of numerals. No reason, therefore, to call Birkir now. This would be tricky to decipher.

23:00

It had begun to snow when Birkir parked his Yaris in the reserved spot behind his house. He remained seated in the car for a little while, reflecting. Finally he made a decision—instead of going inside, he’d walk over to Jónshús and check the situation there.

The falling snow was heavy and wet, and soon the ground was completely white. Birkir felt the snow pile up on his shoulders and in his hair, and now and then he stopped to brush the worst of it off. Between stops, he walked briskly and soon reached his destination. In a parking space just across the street from the house were two men in a car, its engine running and windshield wipers sweeping to and fro against the snow. These must be the plainclothes policemen the chief had put on watch there in case the Sun Poet showed up. He tapped on the side window, and the one sitting at the wheel rolled it down.

“Good evening,” Birkir said.

“Hi.”

“Any signs of life?”

“No.”

“I wasn’t really expecting there would be,” Birkir said. “I’m just going to check on the folks in there.”

“You do that,” said the cop, who then yawned.

In Jónshús, all the lights seemed to be off—except for the glimmer of light coming from one of the living rooms. Birkir caught a glimpse of Rakel at the window.

He trod his way through the yard and went up the steps to the front door. He pressed the bell once, briefly. After a while,

the light above him came on, and someone peeked through the drapes covering a small window next to the door. Birkir knocked and shouted, “Detective division, Birkir Li Hinriksson.”

The door opened and Rakel peered out.

“Sorry to disturb you,” Birkir said.

“What do you want?” Rakel asked. “I haven’t heard anything from Jón, and Fabían is asleep. I gave him a large dose of painkillers.”

“I want to ask you a few questions.”

“You do, do you? I don’t suppose there’s any point in my refusing.”

“I’d be very grateful if you’d cooperate.”

Rakel opened the door and stood to one side. “You’re welcome to come in. We’ll see about the questions.”

It was dark inside. Rakel was wearing a thick bathrobe, and she led the way into the house. She said over her shoulder, “Everyone went to their rooms long ago. They weren’t very happy this evening.”

“Why not?”

“There’s something scary in the air.”

“Is there something you know about?”

“No, it’s just a feeling.”

She ushered Birkir into the living room. A fire was dying in the fireplace, and Rakel added a couple of logs to its embers. Quiet music came drifting from the stereo. A scratchy vinyl record revolved on the turntable. Birkir knew the song but couldn’t work out who the performer was.

“Who’s the singer?” he asked.

“Joni Mitchell. The album’s

Blue

, from 1971. This is my kind of music. The old hippie records. We have a bit of a collection.”

“Were you listening? I’m sorry if I disturbed you.”

“I was just sitting here alone, thinking,” Rakel said, offering Birkir a seat. “There’s so much going on. Times change.”

She sang quietly along with the music—“Blue songs are like tattoos”—but stopped after one line.

“Were you into the hippie culture?” Birkir asked her.

“The hippies had the most beautiful vision of the twentieth century, but many things in the movement also went wrong. The Woodstock festival was in many ways the pinnacle of that era, but the Manson murders, in the same week of August 1969, were its nadir. Sadly, few could properly handle the freedom the hippies created for themselves and the rest of that generation. I just try to focus on the beautiful things.”

“You’re worried about Jón, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Has he been unbalanced lately?”

“He’s been agitated and restless.”

“Were there symptoms of mania?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. He’s not stable, that much is certain. His bipolar disorder is usually only a problem when he does a lot of heavy drinking. But he’s been sober lately. And he hasn’t been talking to us—when he’s manic he’s usually very gregarious and loud.”

Birkir said, “I know that those of you who lived with Sunna in Sandgil have wanted to talk with ex-Sheriff Arngrímur Ingason Esjar. Helgi told me the whole story. Are you aware of some kind of action that Jón has planned?”

“No.”

“Do you think it’s plausible?”

“Maybe.”

“What were they going to do to Arngrímur?”

“I don’t know. They haven’t included me in their plans lately. I’ve always been so cautious. They called it fear.”

“But would you have wanted to get Arngrímur to confess?”

“Yes, that would have been good. None of us emerged from those events unscathed. We survived them, each in our own way, but there was always this question: Why did it have to happen?”

“I know you were all very fond of Sun. What made her so special?”

“She was my best friend.”

“Tell me more.”

Rakel pointed at a framed drawing hanging on the wall, its paper yellowed and creased where it had been folded. “That’s a picture of Sun that Fabían drew a long, long time ago,” she said. “It’s the only one of her that we have.”

Birkir stood up to take a closer look. It was a fine drawing of a beautiful girl playing a guitar.

“But it’s better than any photograph could have been,” Rakel added. “Sun was singing when she woke up and singing when she went to sleep. She loved life as only the young can. She never argued with anyone, and soothed all who were bitter. The rest of us attempted to embrace the hippie way of life, but she was simply a child of nature. She came from the sparsely populated country of Northwest Iceland and didn’t feel the need to copy anybody. She was a genuine flower child. The two of us went for long walks in the area around Sandgil, sometimes a long way into the hills, and even all the way up Mount Thórólfsfell—there was a view into the Thórsmörk National Park when visibility was good. Sun loved everything that was beautiful—landscape, music, poetry, pictures.”

“Was she completely perfect?” Birkir asked.

Rakel smiled. “She was scared of mice.”

Her smile disappeared as she added, “And fire.”

B

irkir got back home just after midnight. He slept soundly for most of the night, but toward early morning he woke with a start from a dream in which Jón the Sun Poet had caught him and was forcing him into a foul-smelling hessian sack. He lay a long while thinking about the dream. In it, he hadn’t been scared of Jón—it was the smell. Sometimes he dreamed about an unfamiliar smell—it could be a good smell or a bad smell, but it was always something he didn’t recognize from daily life. Something from his childhood, likely from Vietnam. He closed his eyes and inhaled through his nose, trying to find some image that went with this smell, but nothing came to him. It was as though he hit a wall whenever he thought about the day he arrived at that Malaysian refugee camp. He couldn’t recall anything in context before that time, just obscure fragments that popped up in response to some everyday event.

He remembered, suddenly, that he had lots of work to do at the police station, and he got out of bed and rushed to get himself ready for an early start. He switched on the kettle to boil some

water while he took a quick shower and shaved, after which he made himself a cup of tea and a piece of cheese on toast. Having eaten his breakfast, he headed out.

On his desk was an envelope from Anna. It contained a printout of the image she’d retrieved from the notepad in Jónshús. She had erased all traces of earlier stuff, leaving just the most recent message—the one Jón had written:

What did these numbers mean? Did they have any bearing on the case?

He was scratching his head over this when Gunnar hobbled in on his crutches, wearing a cervical collar. It took him a good while to sit down.

“You should have stayed home,” Birkir said.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s what Mom said, too.” Gunnar sneezed and wiped his face with the sleeve of his jacket. “Goddamned cold,” he said nasally.

Birkir passed him the roll of paper towels he’d fetched for him the previous day.

“Thanks,” Gunnar said, blowing his nose. “Anything new?”

Birkir showed him the paper with the numbers on it. “What do you think these are?”

“Bingo numbers?” Gunnar said.

“I figure they’re directions to someplace,” Birkir said, and explained where the paper came from.

“I pass,” Gunnar said. “I can’t make any sense of this.”

Birkir’s cell phone rang. It was the front-desk duty officer. “There’s a woman here wants to speak with you.”

It was Rakel. She handed Birkir an envelope. “I went for a walk this morning like I do every morning. I came across Jón, waiting for me by Hallgríms Church—he knows my regular route. He said the cops were watching our house, so he couldn’t come home. He said they were probably bugging his phone, too.”

“That’s possible,” Birkir said. He didn’t know what measures the chief of police had set up.

Rakel continued, “He gave me this envelope and asked me to give it you. I brought it straight here.”

Birkir opened the envelope. It contained an old audiocassette, nothing else.

“I don’t know anything else about this,” Rakel said. “I swear. You take it and do with it whatever you have to. I hope I can go back home to look after Fabían. You know you can find me there.”

Birkir nodded and watched her go. Then he went to see the chief of police, who’d just arrived at his office.

“I guess we’re meant to listen to this,” Birkir said, showing his boss the cassette. He explained how it had come to them.

“Do we have such a thing as a cassette player?” the chief asked.

Birkir said, “The old radio in the kitchenette has one.”

“Let’s check it out,” the chief said, and stood up. They headed to the kitchenette, which was soon pretty crammed as others joined them. Birkir inserted the tape and pressed “Play.”

The voice sounded tired, but spoke clearly. “My name is Arngrímur Esjar Ingason. I was appointed sheriff of the Rangárvellir district on April fourth, 1972, and remained in that

office until February sixteenth, 1975. Since May fifth, 1975, I have worked abroad for the Icelandic Foreign Ministry.”