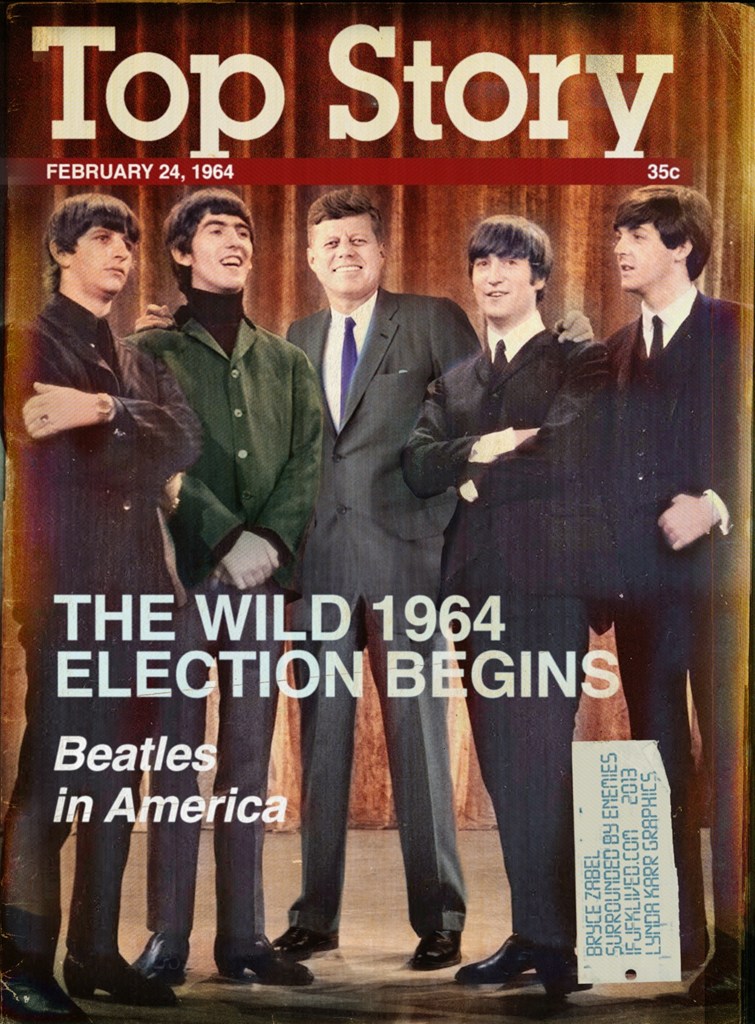

Surrounded by Enemies (9 page)

Read Surrounded by Enemies Online

Authors: Bryce Zabel

By now, the meeting at Hyannis Port was being fueled by a third pot of coffee. “How do we stop them?” O’Donnell asked. “How do we stop the U.S. House and the Senate from doing what they have a legitimate right to do without making them wonder why we’re stopping them?”

“National security,” Bobby Kennedy said at once.

John Kennedy lit a rare cigar and drew on it before speaking: “We can’t use that without scaring people and making them ask even more questions.” The statement hung in the air like cigar smoke, as people read between the lines: Asking questions in an election year was to be avoided at almost any cost.

Pierre Salinger could hold forth with reporters for hours on end but when he was in with the President and his men, he often held back. So it was surprising when he blurted out, “It’s simple. Congress can’t do the job right during an election, and the people will recognize that after we explain it properly.”

It was almost December, argued the Press Secretary. The 1964 election, just eleven months away, would feature a hotly contested presidential race, made even more unpredictable by current events. Therefore, the U.S. Congress could hardly be trusted to investigate the attack in Dallas. They would be reaching conclusions in the midst of highly charged partisan wars that were certain to exist. Impartiality would be impossible.

Kenneth O’Donnell agreed to that line of reasoning. “The administration has a moral obligation to set up an honest nonpartisan investigation. The matter is too important to be left to Congress. We need to form an independent committee.” It was quite an argument, given that Congress was exactly where the Constitution said important matters had to go.

Kennedy exhaled cigar smoke. “In the Navy, we’d call that a gun deck job,” he said, using a term usually reserved for an exercise that was bullshit from top to bottom. “But it’s probably the way to go.”

As a general rule, President Kennedy had little patience for committees and the meetings they liked to have. His back pain made sitting through them excruciating, and usually they had no real purpose and accomplished nothing of value. If you wanted something done, you surely shouldn’t ask a committee to do it. Even during the Cuban Missile Crisis, he’d been happy to let Bobby run the ExComm and not just because those attending would speak more freely if the President wasn’t in the room.

In his own mind, JFK thought a committee would be no more competent at its work than most of the ones he had served on since going to Congress. It would, however, keep the work private until the election. Then, with a second term, the facts could fall where they may. In retrospect, it was an unusually optimistic position.

Everyone had his own opinion about what needed to happen next, particularly who should head any committee, but all waited for Bobby to go first. This happened often, and it was clear that he was speaking for his brother. “I’ve received some suggestions, but there’s one in particular we may want to explore.” He was asked where that suggestion came from. “It’s better for all of us if we keep the source confidential,” he said, ending that line of questioning.

The suggestion was Earl Warren, chief justice of the United States Supreme Court.

“We talked this morning. I asked him hypothetically if he would lead such a committee, and he said yes. He said he would be honored, as a matter of fact, if that’s the direction we decide to go.”

So there it was. “That’s not bad,” thought O’Donnell out loud. “But can we trust him not to go wandering off on his own?”

It was a valid question. Earl Warren was a Republican. He’d been the attorney general and the Governor of California, and he’d run for Vice President with Thomas Dewey back in 1948 against Truman. He wanted to run for President on his own in 1952. After being appointed to the Supreme Court by President Eisenhower, Warren had, to many, veered left during his years as chief justice. Now the John Birch Society had him targeted. “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards dotted the landscape, especially throughout the South.

The President weighed in. “He understands that we can’t let a nuclear war start because a few congressmen need to distract voters from their own incompetence.”

Bobby nodded. “Warren will play ball. I’ll put Hoover in charge of the investigation. He’s already made up his mind about Oswald. We’ll just see that they don’t report until after November.”

The meeting broke up a few minutes later. The administration had a plan.

On Monday, December 2, 1963, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy signed Executive Order No. 11130, creating a commission to investigate the assassination of Governor John B. Connally of Texas, the death of Special Agent Clint Hill and the death of Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit on November 22, 1963. The commission was directed to evaluate all the facts and circumstances surrounding the ambush, including whether or not it was specifically targeted against the President, and to report its findings and conclusions to the President for submission to the U.S. Congress with all due haste. Kennedy explained the mandate of the commission to reporters in the White House Briefing Room:

The subject of the inquiry is a chain of events that saddened and shocked the people of the United States and, indeed, the world. By my order establishing this commission, I hope to avoid parallel investigations and to concentrate fact-finding in a body having the broadest national mandate.

Then the President introduced Chief Justice Earl Warren, who looked like everybody’s kindly grandfather. Joining President Kennedy for the announcement, Warren addressed the assembled press in a dark blue suit instead of his usual judicial robes.

We will conduct a thorough and independent investigation of these tragic events. We will cooperate with the Dallas Police Department in any way we can. Obviously, they have a criminal investigation and trial to conduct. We do not want to interfere with Mr. Oswald’s right to a fair trial. If he is found guilty, we do hope to determine whether his role was of his own device or whether he acted as part of a possible conspiracy.

The chief justice announced the makeup of what was nearly instantly called the Warren Commission: two senators and two representatives, split evenly between the Republicans and Democrats; plus four members from outside the Beltway who were not actively serving in Congress; and of course, Warren himself.

The senators were Washington Democrat Warren Magnuson and none other than Illinois Republican Everett Dirksen. Kennedy and his team had decided that the devil they knew was better than the devil they didn’t. Dirksen wanted the status of being on the committee. But even his ego would not be enough for him to try to take over the spokesman’s position from the chief justice of the Supreme Court. With his own position in history secured, Dirksen was the first to condemn his own idea of a congressional investigation as “duplicative.”

As far as senators went, Warren Magnuson was deeply experienced, well liked and certainly of Dirksen’s stature, if not his prominence. Magnuson, it was also pointed out by a few news reports, had been the beneficiary of a 1961 fundraiser where President Kennedy had come to Seattle and gotten three thousand people to pay $100 each to hear JFK sing the senator’s praises. The two men had history in the club that was the U.S. Senate. The Kennedy team felt he would be loyal if they needed him on a particular issue.

The representatives were Democrat Hale Boggs of Arkansas and Republican Florence Dwyer of New Jersey. Boggs was the Majority Whip in the House and got the job after Majority Leader Carl Albert said he could not run the House and serve on the commission at the same time. Dwyer was one of the very few women in either the House or Senate. The Kennedy team liked her because she had sponsored the Equal Pay Act that had just passed. Looking ahead to the 1964 election, it would be good to have appointed a woman who believed in equal rights and was from the opposing party. When President Kennedy had first met her, Dwyer had said, “A Congresswoman must look like a girl, act like a lady, and think like a man.” For Kennedy, she was the perfect Republican.

Even better, the thinking went, the four “politicians” could be balanced out with four others who could be presented as keeping the Warren Commission impartial. Appointed were former president of the World Bank, John J. McCloy; civil rights leader James Farmer; ailing news legend Edward R. Murrow; and New York City’s young superintendent of schools, Calvin Gross.

These four so-called “wild cards” were carefully calibrated so that none would stand out enough to cause Congress to reject the idea of the Warren Commission in favor of its own committee. McCloy’s reputation was unassailable. Farmer brought along the black community. Murrow had already received congressional approval for his Voice of America work. Gross was a wild card within the wild cards, selected for his can-do attitude on the front lines of education.

“This is one advantage an independent commission has over a congressional investigation,” Kennedy offered. “By the very nature of things, a congressional investigation is bound to be partisan. This commission will be anything but.”

The time estimated for the job was about a year, plus or minus. The public reaction to Oswald’s trial and whether any further arrests would be made were unknown elements in the equation. As for the hot potato that this could become, given next year’s presidential primaries and general election, both the President and the chief justice agreed the report would not be delayed or moved forward based on any political considerations, be they favorable or unfavorable to the administration.

What the Kennedys already knew and the public had yet to fully comprehend, was that the Warren Commission would be receiving testimony, files and theories from the FBI which, at that time, seemed to be leaning strongly toward pinning the matter on Oswald and moving on.

The commission had no funds or authority for independent investigation. It would have to make whatever case it felt needed to be made from other people’s evidence.

Against the backdrop of this high-stakes gamesmanship, the trial of Lee Harvey Oswald loomed large. Oswald, who at the beginning had talked much more than anyone had expected, had suddenly gone quiet at the insistence of his attorney, William Kunstler. The New Yorker, however, was anything but quiet, arguing his client’s innocence regularly to all takers. The one thing that Kunstler said that grabbed everyone’s attention, however, was the fact that Lee Harvey Oswald was going to take the stand in his own defense. Kunstler dropped this bombshell on a crowd of reporters outside the Dallas courts building after a hearing about whether Oswald’s federal troubles might supersede local jurisdiction.

My client is innocent. It is not up to him to prove that, as you all know, and he is under no legal obligation to testify, a right protected by the U.S. Constitution. It is up to the Dallas District Attorney to prove that he is guilty. Lee Oswald, however, will testify, under oath, that the only mistake he made on November 22 was coming to work at the Texas School Book Depository on a day when someone chose to shoot at the President of the United States. Powerful forces have framed him, ladies and gentlemen. He is exactly what he said on the day he was arrested. A patsy.

Day in and day out, Kunstler embellished his reputation as a radical firebrand and showed that he intended to carry out an aggressive defense of Lee Harvey Oswald. Besides proclaiming his client’s innocence, he declared that all of Oswald’s statements before he gained legal representation were obtained under duress and were therefore “inoperative” — the attorney’s word, which was later widely quoted and ridiculed.

When confronted with a statement from Dallas D.A. Henry Wade that a recovered bullet matched the gun that Oswald had bought by mail-order before the shooting, Kunstler was unfazed. “Henry Wade can say whatever he damn well pleases. He’s a state lackey, and they pay him to get convictions. He doesn’t care that he’s prejudicing the jury pool against my client.”

Kunstler would later say in his 1967 book

The People Versus Lee Harvey Oswald

that he was “preparing the battlefield.” He wanted to be the underdog, citing the fact that he was a New York Jew fighting in the buckle of the Bible Belt, and hoping that some of that would rub off on his client. He continually invoked his theory of a grand right-wing conspiracy that decided the President was too progressive. He railed against conspirators, real and imagined, with a vested interest in nipping change in the bud. By “change,” Kunstler meant peace talks, black civil rights and strengthening organized labor.

The irony, of course, is that the Kennedy men all seemed to agree with William Kunstler about the likelihood of conspiracy, even as they hoped the Warren Commission — which they had empowered as the official investigation — would come to the opposite conclusion. It was, to use a word favored by psychologists, a “cognitive dissonance” that would make living in the White House during 1964 the trickiest year yet.

By mid-December 1963 the nation was exhausted. It had been hit with the impact of what felt like a stressful brush-with-death of a family member, combined with the unsettled feeling that won’t go away after being mugged. America was high-strung and stressed-out.

Holiday shopping sales figures were headed for a historic low. Retail organizations implored President and Mrs. Kennedy to consider lighting more public Christmas trees but were rebuffed for security reasons. The First Lady’s social secretary Liz Carpenter explained the feeling in her own memoirs, tying the public’s down mood in part to the loss of the Kennedys’ infant son from respiratory stress disease: “People understood that the President and Mrs. Kennedy needed some time alone. They’d suffered the death of their son that year as well… and then what happened in November. It was just a bit too much for anyone.”

The mood of Christmas 1963 was one of somber and earnest prayer for many people. After the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis hung over the 1962 holiday season, now the ambush in Dallas hung over this one. America’s holidays had been hijacked by a couple of frightening and disturbing near-misses. Many people did without holiday parties and spent time with their families.

No one talked about politics, at least publicly. December had been declared the lull before the storm, but politics, particularly presidential politics, were gone only temporarily. In many homes of America’s political elite, there was a great deal of thinking and strategizing.

This current quiet, sold as respect for the dead, would end soon.