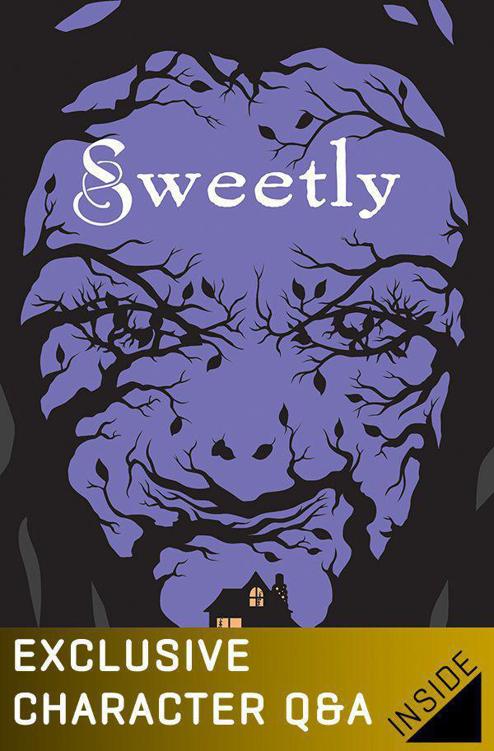

Sweetly

by Jackson Pearce

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY

New York Boston

Character Interview: Gretchen and Rosie

T

O

S

AUNDRA

(

FOR ALL THE CANDY

)

T

he book said there was a witch in the woods.

That’s why they were among the thick trees to begin with—to find her. The three of them trudged along, weaving through the hemlocks and maples, long out of sight of their house, their father’s happy smiles, their mother’s soft hands.

A sharp ripping sound bounced through the trees. The boy whirled around.

“Sorry,” one of the girls said, though she clearly didn’t mean it. Her cheeks were still lined with baby fat and her hair was like broken sunlight, identical to the girl’s standing beside her. She held up the bag of chocolate candies that she’d just torn open. “You can have all the yellows, Ansel, if you want.”

“No one likes the yellows,” Ansel said, rolling his eyes.

“Mom does,” one of the twins argued, but he’d turned his back and couldn’t tell which one. That was how it normally was with them—they blended, so much so that you sometimes couldn’t tell if they were two people or the same person twice. The sister with the candy emptied a handful of them into her palm, picking out the yellows and dropping them as they continued to trudge forward.

“When we find the witch,” Ansel told his sisters, “if she chases us, we should split up. That way she can only eat one of us.”

“What if she catches me, though?” one of the girls asked, alarmed.

“Well, what if she catches me, Gretchen?” Ansel replied.

“You’re bigger. She should chase you,” the other sister told him, pouting. “That’s the way they work.” She was the only one who claimed to know the ways of witches—she was the one with the stories, the made-up maps, the pages and pages of books stored away in her head. She reached into her twin’s bag of candy and pegged Ansel in the back of the head with a yellow candy. He didn’t react, so she prepared to throw another one—

“Wait… do you know where we are?” he asked.

One of the twins raised her eyes to the forest canopy and scanned the closest tree trunks, while her sister turned slowly in the leaves. They knew these woods by heart but had never ventured quite so far before. The shadows from branches felt like strangers, the cracks and pops of nature turned eerie.

The twins simultaneously shook their heads and their brother nodded curtly, trying to hide the fact that being out so far made him uneasy. He hurried forward, eager to keep moving.

“Ansel? Wait!” one asked, and ran a little to close the space between them. “Are we lost?”

“Only a little,” he answered, jumping at the sound of a particularly loud falling branch. “Don’t be scared.”

“I’m not,” she lied. She began to wish she’d packed peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for their adventure, instead of two Barbies and a bag of candy, which Gretchen had almost finished off anyway. What if they were stuck out here past dinnertime?

“Besides,” Ansel said over his shoulder, “maybe she’ll be a good witch, like Glinda, and help us get unlost.”

“I thought you said she might want to eat us.”

“Well, maybe, but we won’t know until we find her. Unless you want to go back,” Ansel said. He didn’t entirely believe the stories about the witch, but his sisters did and he didn’t want to ruin it for them. Another pop in the woods made him jump; he shook off the nerves and sang their favorite song, one from a plastic record player that had been their father’s.

“In the Big Rock Candy Mountain, you never change your socks.”

The twins began to hum along, adding words here or there, until they got to the line all three of them loved and they sang in unison.

“There’s a lake of stew and soda, too, in the Big Rock Candy Mountain!”

The familiar words calmed them, made things fun again, as though their combined voices swept the fear away.

Ansel was about to begin another verse when a new noise came from farther in the forest—not a pop, not a crack, but a footstep. A slow, rolling foot on dried leaves, then another, then another. He grabbed his sisters’ hands, one of their sticky palms in each of his. The bag of candies fell to the ground and scattered, rainbow colors in the dead leaves.

They waited. There was nothing.

And yet there was something—there was something, something breathing, something dripping, something still and hard in the trees. Ansel’s eyes raced across the trunks, looking for whatever it was that he was certain, beyond all doubt, had its eyes locked on them.

“Who’s there?” Ansel shouted. His voice shook, and it made the twins quiver. Ansel was never scared. He was their big brother. He protected them from boys with sticks and thunderstorms.

But he was scared now, and they were torn between wonder and horror at the sight.

Nothing answered Ansel’s question. It got quieter. Birds stilled, trees silenced, breath stopped, his grip on his sisters’ hands tightened. It was still there, whatever it was, but it was motionless, waiting, waiting, waiting…

It finally spoke, a low, whispery voice, something that could be mistaken for wind in the trees, something that made Ansel’s throat dry. He couldn’t pick out the words—they were torn apart, and they were dark. Low, guttural, threatening.

The words stopped.

And it laughed.

Ansel squeezed his sisters’ hands and took off the way they had come. He yanked them along and ran fast as he could, over brush and under limbs. The twins screamed, a single high-pitched note that ripped through the trees and swam around Ansel’s head. He couldn’t look back, not without slowing.

It was behind them. Right behind them, chasing them.

Gretchen stumbled but held tightly to Ansel, let herself be dragged to her feet just as something grasped at her ankles, missed. They had to move faster; it was coming, crunching leaves, grabbing at the hems of their clothes.

It’s going to catch us.

The twins slowed Ansel down—their joined hands slowed everyone down. They’d promised to split up so the witch could eat only one of them, but now…

It’s going to catch us.

Ansel lightened his grip, just the smallest bit, and suddenly his hands were free and the three of them were sprinting through the trees. The thing behind them roared, an even darker version of the words they’d heard earlier.

Both twins knew the other couldn’t run much longer. Did Ansel know the way out?

Candy.

On the ground, yellow candies. Ansel was following them, slicing around trees while the twins followed along desperately, eyes focused on finding the next piece, the trail back to the part of the forest they knew. The monster leapt for one of the twins, missed her, made a breathy, hissing sound of frustration. She dared to glance back.

Yellow, sick-looking eyes found hers.

She turned forward and sped up, faster than the others, driven by the yellow eyes that overpowered the sharp aches in her chest, her legs begging for rest. There was light ahead, shapes that weren’t trees. Their house, their house was close—the candy trail had worked. She couldn’t feel her feet anymore, her lungs were bursting, eyes watering, cheeks scratched, but there was the house.

They burst from the woods onto their cool lawn.

Get inside, get inside

. Ansel flung the back door open and they stumbled in, slamming the door shut. Their father and mother ran down the stairs, saw their children sweaty and panting and quivering, and asked in panicky, perfect unison:

“Where’s your sister?”

T

he truth is, I can’t believe it took our stepmother this long to throw us out.