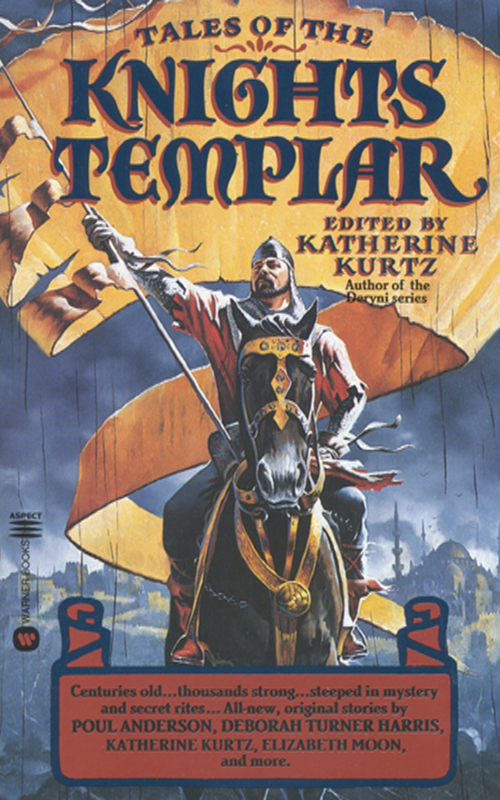

Tales of the Knights Templar

Read Tales of the Knights Templar Online

Authors: Katherine Kurtz

The Comer and Faith to Maintain Boms Through the Ages

1167

A.D.

.… Nazareth …

“The City of Brass” by Deborah Turner Harris and Robert J. Harris: Saladin’s forces are poised for Allah’s victory over Christ; in a lost temple of magic and horror, the demon Baphomet will defeat all the gods…

1314

A.D.

… Paris …

“Obligations” by Katherine Kurtz: Sir Adam Sinclair, the Adept, must travel the Astral Path to a past life and beyond, seeking the fate of a tormenting, 700-year-long Templar quest…

1746… Culloden Moor, Scotland…

“Word of Honor” by Tanya Huff: The Bonnie Prince’s hope to reclaim his kingdom rested upon Templar magic—but the battle was turned by a coward’s theft, a wrong that could only be made right from beyond the grave…

1952 … Texas …

“Knight of Other Days” by Elizabeth Moon: In a border hamlet, a

bruja

and a doomed mortal must decide the fate of a Templar stone that stops “the dead who could curse the world”…

Forever…

“Death and the Knight” by Poul Anderson: At any cost, the Time Patrol must stop a future scientist and his lover from saving the Templars—and destroying history!

If you purchase this book without a cover you should be aware that this book may have been stolen property and reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher. In such case neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

Copyright © 1995 by Katherine Kurtz

All rights reserved.

Aspect is a trademark of Warner Books, Inc.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: April 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56122-8

To the Knights of the Order of the Temple of Jerusalem, Past, Present, and Future

Non nobis, Domine, non nobis,

sed nomini tuo da gloriam.

Contents

Introduction

by Katherine Kurtz

The City of Brass

by Deborah Turner Harris and Robert J. Harris

End in Sight

by Lawrence Schimel

Choices

by Richard Woods

Obligations

by Katherine Kurtz

Word of Honor

by Tanya Huff

1941

by Scott Macmillan

Knight of Other Days

by Elizabeth Moon

Stealing God

by Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald

Death and the Knight

by Poul Anderson

I

n 1118, a French crusader called Hugues de Payens and eight fellow knights founded the Military Order most commonly known as the Knights Templar. During the two centuries that followed, the Templars established a well-deserved reputation as (among other things) superb fighting men and incomparable financiers. In the less than two hundred years the Order formally existed, they also achieved a notoriety unprecedented among other religious or chivalric bodies anywhere in the world.

On October 13, 1307, a day so infamous that Friday the 13th would become a synonym for ill fortune, officers of King Philip IV of France carried out mass arrests in a well-coordinated dawn raid that left several thousand Templars—knights, sergeants, priests, and serving brethren—in chains, charged with heresy, blasphemy, various obscenities, and homosexual practices. None of these charges was ever proven, even in France—and the Order was found innocent elsewhere—but in the seven years following the arrests, hundreds of Templars suffered excruciating tortures intended to force “confessions,” and more than a hundred died under torture or were executed by burning at the stake.

The ostensible reason for suppressing the Order of the Temple had been to eradicate heresy; a more pragmatic motive had to do with seizing the vast wealth of the Templars for the King of France—and eliminating a too-powerful Order that answered only to the pope. (The Templars had denied Philip admission to the Order as an honorary lay knight, so personal pique may have been a motive as well.) Neither the Order’s champions nor its detractors failed to note that both Philip and the pope, who had abandoned the Order to Philip’s avarice, were to die within a year of being cursed by the last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, as he and his Preceptor for Normandy were burned at the stake on March 14, 1314.

The preceding is a bare-bones synopsis of the Order’s rise and fall, but a more detailed look at the Templars’ history suggests more complicated circumstances that all added to the legendary stature the Order enjoys today. Historical perspective places the birth of the Order in the immediate aftermath of the Christian capture of Jerusalem in 1099, which led to increasing numbers of pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land to visit Jerusalem and other holy places. Despite the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, with a royal line of Western kings, travel in the area remained dangerous. Defense of the Christian-held lands was difficult, and men could seldom be spared to patrol the travel routes and protect pilgrims.

The Hospitaller Order, later to become the Knights of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, had been founded in 1113 to house and minister to sick and injured pilgrims, but they did not immediately expand their role to include the protection of these pilgrims. Into this void came a French nobleman from Champagne called Hugues de Payens, kin to the counts of Troyes, to found a second crusading Order initially calling themselves the Poor Knights of Christ. Tradition preserves the names of the founding nine in a list that probably vacillates between the factual and the mythic: Hugues de Payens, Geoffroy de Saint-Omer, Andre de Montbard, Andre de Gondemare, Payen (or Nivard) de Montdidier, Archambault de Saint-Aignan, Godefroy Bissor, Roffal (or Rossal or Roland), and Hugh Comte de Champagne—though the latter is known to have joined later. Undertaking to guard the pilgrimage routes and live as a religious community of warrior-monks (and under guidance from canons of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem), they adopted a religious rule based on that of St. Augustine and made vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience before the Patriarch of Jerusalem.

Their offer of assistance was welcomed by King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, who granted them accommodation on the site of King Solomon’s Temple, the cellars of which were said to have housed King Solomon’s stables. Thus derived their eventual name: Pauperes Commilitones Christi Templique Salomonis—the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, later known as the Knights of the Temple, or Knights Templar.

For men vowed to protect pilgrims and holy sites, these first Templars do not seem to have done a great deal of protecting during the first few years of their existence, or to have attracted much interest in East or West. They recruited few, if any, new members. They lived in real poverty, without any distinctive attire or significant military presence. An early seal of the Order shows two knights riding on the same horse, said to be symbolic of their shared poverty and brotherhood. (This does not reflect later reality, for while individual Templars owned nothing, each knight would have required at least two or three horses in order to function in any military capacity—and sergeants and other lay retainers to support him.)

During that first decade of existence, the greater part of the knights’ energy seems to have been focused on establishing their headquarters underneath the old Temple. Some later historians, searching for an explanation of the Templars’ great eventual wealth, would suggest that the proto-Templars found some fabulous treasure while digging in the old foundations. (At least one esoteric tradition maintains that the real task of Payens and his eight co-founders was to carry out research and excavations that would result in the recovery of certain relics and manuscripts said to preserve mystical and even magical secrets of Judaism and ancient Egypt. According to this tradition, the knowledge thus obtained was transmitted through oral tradition within a secret inner circle whose existence was not even suspected by rank-and-file members of the Order.)

Whatever the true purpose of the founding nine, Hugues de Payens seems to have been ready for the Templars’ next phase by 1127, when he embarked for Europe with five of his knights to seek official recognition by the church. Presenting himself and his companions before the Council of Troyes in 1128, he briefly recounted their history and mission, presented their proposed constitutions, and asked that they be given a rule of their own.

Their petition was successful. The future St. Bernard of Clairvaux gave the Templars a rule of seventy-two articles derived partially from his own Cistercian Rule (which had been based on the Rule of St. Benedict), partially from existing practices already adopted from the guidance of the Patriarch of Jerusalem and the Rule of St. Augustine, and in part based on a rule of Essenian origin known as the Rule of the Master of Justice.

In addition, with Bernard’s concurrence, the knight brothers adopted the snow-white habit worn by the Cistercians and the canons of the Holy Sepulchre, symbolizing purity, and added to a white mantle the red cross of martyrdom, already long worn by crusaders. In all likelihood, the form of cross first used was a red patriarchal cross, with its double crossbar, since the knights had made their original vows to the Patriarch of Jerusalem and hence were his knights; but other forms became more common following papal recognition, including the more familiar Maltese cross, whose eight points symbolized the Beatitudes. Sergeants and squires wore the red cross on black or brown mantles.

A further distinction of appearance that proved an unexpected advantage in the Holy Land was the rule’s requirement that, contrary to European custom of the time, the knights were to crop their hair short but keep their beards long. Since facial hair represented masculinity and virility in Middle Eastern culture, the bearded Templars were regarded by their Muslim foes with far more respect than the long-haired and clean-shaven European crusaders, who were seen as feminine and disgraceful.

By the time of Hugues’ death in 1136, the Order was flourishing, with preceptories and commanderies in France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, ever-increasing grants and bequests of lands and revenues, and a growing reputation for ferocity in battle. Hugues had been a pious knight with determination and leadership abilities; his successor as Grand Master was Robert de Craon, or Robert the Burgundian, who brought administrative skills to the office.

By 1139, Robert had gained the unequivocal support of the papacy, when Innocent II created a new category of chaplain brothers for the Templars. Placing the Order under direct papal jurisdiction answerable only to him, Innocent further gave the knights the autonomy to act independently of the ecclesiastical and secular rulers. In addition, he extended their function beyond the mere protection of pilgrims, exhorting them to defend the Catholic church against all enemies of the Cross.

This broadening of their mandate enabled the Order to grow mightily in the decades that followed, rapidly establishing preceptories, commanderies, and other holdings in Spain, Portugal, Germany, and elsewhere in Europe. Fighting under the distinctive black and white battle standard called Beauceant, they soon presented a formidable military presence in the Holy Land.

Single-minded of purpose, their very motto proclaimed their allegiance:

Non nobis, Domine, non nobis sed nomini tuo da gloriam

—“Not to us, Lord, not to us but to Thy Name give the glory.” By their vows and their very rule, they must follow orders without question, might not retreat in battle unless outnumbered at least three to one and only then upon direct order, neither gave nor received quarter, could not be ransomed, must stand and die if so ordered. And many of them did.

By the 1170s, the combined strength of the Temple and the Hospital would have made up close to half the effective Christian fighting force in the Holy Land, equally divided, with perhaps three hundred Knights Templar in the Kingdom of Jerusalem (along with their ancillary sergeants, squires, and other functionaries) and probably comparable numbers maintained in Antioch and Tripoli. And as the crusaders gained victories, both the Temple and the Hospital were given castles to garrison, forming a network of strongholds throughout the lands held by the Christians.

It was not to last. Though the Templars had become a powerful and indispensable part of the defense of the Holy Land, Jerusalem fell to the forces of Saladin in the summer of 1187, following the Frankish defeat at the Horns of Hittin.

Whereon hangs our first tale. One of the charges later made against the Templars was that they had consorted too freely with the Saracens, perhaps even taking on religious taints. One of the names ascribed to the idol supposedly worshiped by the Templars was Baphomet, a corruption of the name Muhammad—a particularly specious connection, since the Muslims abhorred physical representations of their Prophet. (Another interpretation renders Baphomet as Sophia, which could link with more esoteric connections.)