Target: Rabaul (3 page)

Authors: Bruce Gamble

It was barely midmorning, the sun still hours from its zenith, as the eight survivors came to grips with their situation. They were alone in the middle of the Bismarck Sea, their world reduced to a few square yards of yellow neoprene and some meager supplies, which did not include fresh water.

No one was thinking of Sydney anymore. Nor could any of them have imagined, even in their worst nightmares, the terrible odyssey that lay ahead.

CHAPTER 1

A Pirate Goes to Washington

L

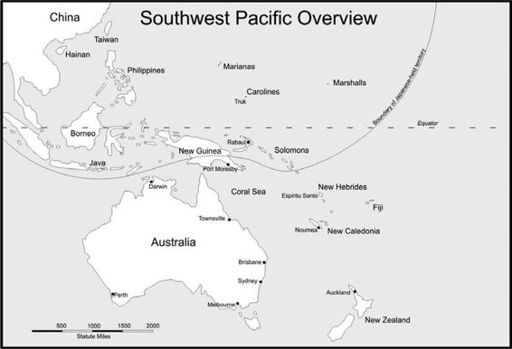

IEUTENANT GENERAL GEORGE

Churchill Kenney was on a roll. At age fifty-three, as commander of all Allied aerial forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SOWESPAC) and commanding general of the U.S. Army’s Fifth Air Force, he had just achieved one of the most decisive air-sea victories in history. During a three-day battle in early March 1943, his American and Australian squadrons practically annihilated a major Japanese convoy in the Bismarck Sea. Sixteen ships were en route to New Guinea with thousands of fresh troops and tons of food and supplies for the desperate, starving garrison at Lae. Kenney’s aircraft sank all eight transports and four of the eight escorting destroyers, killing about 3,500 Japanese troops. American losses were one B-17 and three fighters shot down, totaling thirteen airmen killed or missing.

The lopsided victory came at an opportune time for Kenney. Seven months earlier he had arrived in Australia to replace Lt. Gen. George H. Brett, sacked by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, for substandard performance. Although a capable administrator, Brett had not demonstrated the loyalty that MacArthur demanded, nor had he earned the respect of the men who flew the missions. Most of the bombing raids he sent out were haphazard and ineffective. Brett’s reputation also suffered because he feuded openly with Brig. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, MacArthur’s irascible chief of staff. This wasn’t Brett’s fault: Sutherland tended to meddle with matters outside his bailiwick.

Unlike Brett, Kenney was a hands-on leader. A highly decorated pilot in World War I (and an accomplished engineer known for solving problems), Kenney earned a reputation as an innovator and an “operator” during the developmental years between the wars. The first to install machine guns in the wings of an aircraft, he also invented the parafrag: a small, parachute-retarded fragmentation bomb that could be released at low altitude without undue danger to the bomber’s crew.

Despite these credentials, MacArthur subjected Kenney to a long rant at their first meeting in Brisbane on July 28, 1942. Kenney sat for nearly an hour while the

imperious general expounded on what was wrong with every aspect of the war—especially the air war. When the tirade finally spooled down, Kenney pledged his loyalty and promised to make immediate improvements. Encouraged by this, MacArthur said, “I think we are going to get along all right.”

Less than a week later, general headquarters (GHQ) issued detailed orders for a bombing mission against Rabaul—one that Kenney had already planned. A little sleuthing revealed that Sutherland had intervened. Kenney stormed into his office for “a showdown.” Although Kenney stood less than five and a half feet tall, he bawled out MacArthur’s chief of staff, growling that the top airman in the Southwest Pacific was

not

named Richard Sutherland, and that headquarters had better keep its nose out of his business. When Sutherland reacted defiantly, Kenney issued an all-or-nothing challenge: “Let’s go in the next room and see General MacArthur and get this thing straightened out.”

Sutherland, who relied on MacArthur as his source of power, backed down immediately. Thereafter, Kenney had no interference from Sutherland. As the alpha dog of the air program, Kenney enjoyed direct access to MacArthur and worked closely with him for the next two years.

More importantly, Kenney made good on his promises. In addition to visiting the forward airbases—which his predecessor had failed to do—Kenney rewarded his men for bravery and performance. Personnel regarded as ineffective, particularly officers in administrative positions that Kenney considered “deadwood,” were reassigned or sent packing. With a unique combination of energy and enthusiasm, he restored the morale of the air units almost singlehandedly.

Kenney also demonstrated improvisational brilliance. In late 1942, he turned conventional wisdom on its ear by using C-47 transports to airlift masses of supplies, equipment, and troops to remote airstrips in the mountains, ultimately helping win the battle for Buna.

Perhaps his best innovation, one that captured the imagination of the public back home, was skip bombing. When Kenney took over for Brett, only two heavy bomber groups were operational. Their performance had been disappointing—especially against enemy shipping. A proponent of aggressive, low-level tactics, Kenney worked out the techniques for attacking ships at extremely low altitude. With his aide, Maj. William G. Benn, he demonstrated that if an aircraft released a bomb while flying only fifty feet above the water, the bomb would skip off the surface like a flat stone before detonating against the side of the targeted ship. Kenney placed Benn in command of a B-17 squadron to teach the tactics to others. In time, the crews began using their four-engine Flying Fortresses like stealth bombers. On moonlit nights, they glided quietly down to the wave-tops and skipped their bombs into enemy ships with great success.

But the B-17s weren’t built for such tactics. Due to their enormous wingspan and cumbersome performance, they would have been shot out of the sky had they tried skip bombing in broad daylight. Committed to the concept, Kenney turned

his attention on the more agile twin-engine planes in his inventory, the Douglas A-20 Havocs and North American B-25 Mitchells. He had Maj. Paul I. “Pappy” Gunn, a genius at field modifications, convert several bombers into “commerce destroyers.” With multiple heavy machine guns installed in the nose compartment and along the outside of the fuselage, the aircraft became highly effective gunships, yet they still retained the capability to drop bombs. Whether the planes skipped conventional bombs or scattered clusters of parafrags, the combination of low-level tactics and massed forward firepower proved devastating to enemy targets.

Within months, MacArthur regarded Kenney as his most important general. The two men differed dramatically in appearance and personality, yet their unique characteristics meshed almost perfectly. Each respected the other, both as military professionals and individuals. Kenney often dined with MacArthur, who occupied (with his wife, son, and Chinese amah), the top floor of the posh Lennons Hotel in Brisbane. When the war required them to visit the forward area, Kenney dined with MacArthur at Government House in Port Moresby. Their meals were often accompanied by spirited discussions on a broad range of political and socioeconomic topics. Sutherland usually participated as well, for he was never far from MacArthur’s side.

Following a dinner at Government House in late November 1942, the three generals debated the essential elements of democracy. MacArthur sided with Kenney on a particular argument, which irritated Sutherland. Seeing this, MacArthur teased him, “The problem with you, Dick, is you’re a natural-born autocrat.”

Embarrassed by his boss’s reference to his overbearing personality, Sutherland attempted to redirect MacArthur’s attention. “What about George, here?”

“Oh,” replied MacArthur with delight, “George was born three hundred years too late. He’s just a natural-born pirate.”

Coming from MacArthur, one of the twentieth century’s most compelling personalities, the remark became a source of pride for Kenney. MacArthur appreciated it, too. Whenever one of Kenney’s air units accomplished something praiseworthy, MacArthur would say, “Nice work, Buccaneer.”

As the war progressed, Kenney’s standing grew. When the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) announced an important conference in Washington, MacArthur sent Kenney as the senior envoy from SOWESPAC. Other GHQ staff, including Sutherland, would accompany Kenney to the event, billed as the Pacific Military Conference. Before the trip could get underway, however, Allied intelligence reported the formation of a large Japanese convoy at Rabaul. Kenney and his deputy commander, Brig. Gen. Ennis C. Whitehead, spent the next few days planning an attack on the convoy. The outcome in the Bismarck Sea was total victory, and Kenney’s reputation soared because much of the damage was achieved by his modified commerce destroyers. The low-level attackers had first shredded the enemy ships with machine-gun bullets, then skipped bombs into their hulls at point-blank range.

The battle was still winding down as the conference attendees prepared to leave Brisbane. By that time the outcome was assured, so Kenney woke MacArthur at 0300 on March 4 to inform him of the spectacular results. Despite the early hour, MacArthur was jubilant. He immediately drafted a congratulatory message to the air units: “It cannot fail to go down in history as one of the most complete and annihilating combats of all time,” he wrote. “My pride and satisfaction in you all is boundless.”

The words of praise from MacArthur were profound. By the time the conference delegates landed in Hawaii on March 6, news of the great victory preceded them. Although several GHQ staff were aboard the aircraft, the welcome committee at Hickam Field was there for Kenney. Among them, Adm. Chester W. Nimitz came out to shake Kenney’s hand and learn more about the battle.

Kenney soon discovered, however, that some of his hosts were skeptical of the published claims. On March 7, MacArthur had issued an official GHQ communiqué stating that the Battle of the Bismarck Sea had cost the Japanese three light cruisers, seven destroyers, twelve transports, ninety-five planes, and fifteen thousand troops. The figures almost certainly came from Kenney, based on unconfirmed reports from various squadrons during the early stages of the battle. Kenney habitually exaggerated his achievements—but he outdid himself on this occasion. Moreover, he refused to give ground. If challenged, he waved copies of “operations reports” as proof that the numbers were accurate.

What Kenney didn’t realize was that the victory needed no embellishment. In the wake of the U.S. Navy’s triumph at Midway nine months earlier, good news had been in short supply across the home front. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea was therefore hyped as one of the greatest victories of the war. In addition to receiving credit for the outcome, Kenney enjoyed a boost in status because of his innovative tactics.

After two days in Hawaii, Kenney and his entourage continued their trip, with overnight stops in California and Ohio, before reaching Washington on the afternoon of March 10. Their timing was perfect. Newspaper headlines across the country hailed the recent victory, and Kenney allowed himself to enjoy the attention briefly. “I’m a big shot,” he confided in his diary, “for a while anyhow.”

When the conference began the next morning, Kenney discovered that he was surrounded by heavier brass.

*

All four service chiefs—Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold (U.S. Army Air Forces), Gen. George C. Marshall (U.S. Army), Adm. Ernest J. King (U.S. Navy), and Adm. William D. Leahy (Chief of Staff)—attended the opening session. Several representatives from the South Pacific were also present to assure that Vice Adm. William F. “Bull” Halsey, commander of the South Pacific Area (SOPAC), got an appropriate slice of the procurement pie.

After a few opening remarks, the Joint Chiefs departed for their various offices, leaving the real work of the conference to their high-ranking subordinates. Kenney discovered that his Bismarck Sea fame meant little to these underlings, who seemed to take satisfaction in denying his requests for more men, airplanes, and supplies. Kenney wasn’t the only frustrated commander. The Germany-first policy, agreed upon by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill a year earlier, had severely restricted the pipelines to the Pacific. None of the commanders in the theater, including MacArthur, had been able to obtain more than a trickle of equipment, weapons, or personnel. This was precisely why MacArthur sent Kenney to Washington: the conference presented the best opportunity for the Pacific commanders to voice their collective needs. If Kenney hoped to successfully prosecute the air war in the Southwest Pacific Area, he would have to argue, cajole, beg, borrow, or steal whatever he could get. As the negotiating dragged on, the pressure increased dramatically.

By the end of the second day, Kenney was fed up with all the politicking that slowed the acquisition process. He wasn’t naive—one did not reach flag rank without awareness that favoritism occurred at various levels of the army hierarchy—but he was amazed at the amount of political maneuvering that infected the War Department. That night, he wrote in his diary:

Judge [Robert P.] Patterson, Assistant Secretary of War … is definitely on my side and wants to help in any way to get me some aircraft. He even offered to take the matter up with the President. I asked him not to as I don’t want to go over Arnold’s head unless I can’t get anything any other way. Assist. Secretary for Air [Robert A.] Lovett and [Maj. Gen.] Oliver Echols would both like to help out too but have to take orders from Arnold, who in turn has to deal with the JCS, who get orders from the Combined Chiefs of Staff with the President and Winston Churchill also concerned. Once in a while the Russians put their demands in the pot with threats to get out if they are not met. No wonder Napoleon said he’d rather fight Allies than any single opponent.

*