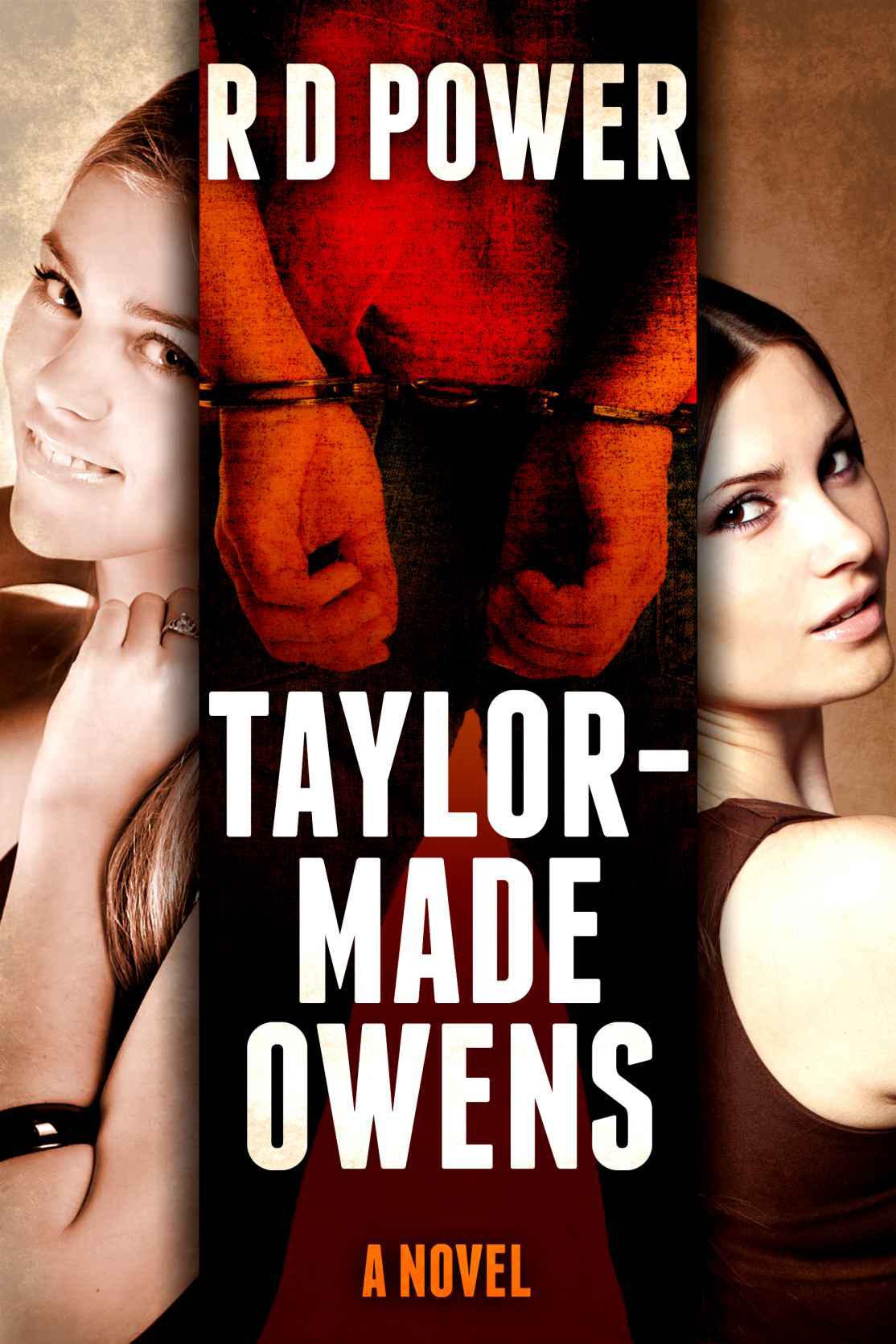

Taylor Made Owens

Authors: R.D. Power

By R.D. Power

Dedicated to:

My wife, Terry

S

trange to think that on certain momentous days, days that will forever change our life, or even end it, we wake up without a clue as to what is about to happen. Saturday the fourth of April was such a day for the Owens family of Framingham, Massachusetts. It was a glorious morning, the kind that makes us happy to be alive. It was the last morning three of the four of them would ever see.

“November 163, you’re cleared for takeoff on runway one five,” said the air traffic controller.

“November 163,” replied Jim Owens, as he applied the throttle and turned the plane onto the runway. He put on full throttle, and the plane accelerated on its takeoff run.

As the plane left the ground, his wife, Jill, cried, “Jimmy, he’s not stopping!” pointing to a commuter plane crossing the runway just ahead. “Oh, God!” she said. The former fighter pilot veered off sharply to the left to avoid the commuter plane, but the maneuver put the small plane into a stall. It slammed into the ground, killing Jim and Tara, their little girl, on impact.

Jill died a few seconds later, her last words gasped to their absent son, “I’m sorry, Bobby.”

Six Years Later

“O

h, did you read this?” Mr. Carlton asked his wife, Gertrude, as he folded up and put down his newspaper and sat down to breakfast. “Some crooks was caught after they broke into some old fogies’ house, tied ‘em up, and stole a bunch of stuff. They should lock ‘em up and throw away the key.”

•

“Mr. Owens, sit down,” instructed a winsome woman of forty to Robert Owens as a police officer escorted him into her office. The officer left. The young teenager sat and tried to marshal a smile through his apprehension. “I’m Lisa Taylor, and I’ll be your caseworker.” She tried to set him at ease with small talk. “Do you go by Bobby or Bob or Rob—”

“Bobby or Bob.”

Despite being so unkempt it looked like he worked at it, the ragamuffin still managed to be pleasing to the eye. She said with a convivial smile, “May I ask if you have a distaste for cutting or combing your hair?”

He relaxed, returned the smile, and responded, “Haircuts are a touchy subject for my foster parents. They gave me fifteen bucks for a haircut a few months ago, but were somehow surprised that when faced with the choice between a hot fudge sundae, ten packs of baseball cards, and a Hershey bar, or a haircut, I made the obvious one, so next time I asked for money for a haircut they handed me a pair of scissors. You can see the result.”

“Okay, well, let’s talk about why you’re here. I understand you’ve admitted to being a part of the gang that raided the Sanderson home last night?”

“What I said was I went into the house to help the fossils after those guys left. Obviously that was a mistake,” he noted with a bitter smirk.

“No, your mistake was not reporting a serious crime that you knew was taking place. The police don’t suspect you of taking part in the crime, but you must have known what was going to happen since you went there with them. You had a responsibility to call for help. The Sandersons might have been injured—or even killed.”

“They said if I told anyone, they’d get me, but the police don’t give a shit about that.”

“Please have some respect, Bobby. Watch your language. Now tell me why you hang out with those troublemakers.”

He considered for a moment how to respond. “You ever see the videos they show in school with the pathetic kid that wanders around the schoolyard all alone, and nobody bothers with him except the bullies? I was the star. I cried a lot in the months after my parents and sister died, and the bullies loved me for it. At first I hid or ran, but it only got worse. After my grandmother died—”

“When was that?”

“A year and a half ago.”

“You moved here to live with her when your parents died?”

“Uh-huh. After she died and I moved into the foster home, I decided never to play the victim again. Any hint of taunting and I’d punch—hard. That was really effective in stopping the bullies, but then, all of a sudden, I was the bully. Now no one will go near me except those guys.”

“So you fell in with the wrong crowd. Tell me what happened last night.”

“They came by my apartment, and I was bored as always, so I went out with them. They’d already made their plan for the home invasion and picked out the targets. They told me while we were walking there. I tried to think of a way to get out of it, but I couldn’t, so when we got there I just told them I wouldn’t do it. They threatened to get me if I squealed, as I told you, and went ahead with their plan. I hid outside. The old lady was screaming and crying. I felt sick just hearing it. After they ran off, I went in and found two old people bound and gagged, lying on the floor. The woman was crying, and the man was unconscious. I think he was having trouble breathing through the sock they stuffed in his mouth. I untied them and helped the man to the couch when he revived. The woman called the police, so I left. Those fucking retards—”

“Bobby, please!”

“Sorry. Those fucking mentally challenged fellows wore balaclavas, but left fingerprints everywhere, and called each other by their real names. The cops arrested the four of them this morning. They ratted on me, so here sits your newest juvenile delinquent case at your mercy, kind, pretty lady.”

“No more cursing. Understand? You don’t think you did anything wrong?”

“Wrong, no. Stupid, yes. If I just left, I wouldn’t be in this mess. That’ll teach me to lend a helping hand, I guess.”

“Don’t take that lesson. It’s only because of what you did for the Sandersons that the police are giving you this second chance. Anyway, you were already in trouble with this other charge.”

He started fidgeting.

“Tell me what happened at the sports store, and what lesson you learned.”

“A misguided youth took a little something, but he redeemed himself when he helped a pair of relics, so the kind, pretty lady let him go.”

“What happened at the sports store?” she repeated, more authoritatively.

“I still have the glove my father bought me when I was five. I needed a new one, so I went to Harry’s Sports. I wasn’t satisfied with the selection available for the dollar sixty-eight I had to my name, so I chose the nicest one, tucked it under my jacket and walked out of the store.”

“Do you feel any remorse for taking the glove?”

“Yeah, sure.”

“You’re not very convincing, Mr. Owens.”

“Okay, the truth is I was thrilled I finally had a new mitt. I had no other way to get one. How am I supposed to play baseball without a fuc—without a glove? I love baseball and I was really good, but I haven’t played since … Ah, I don’t have the money to join a league anyway, so who cares, right?” He lowered his eyes and struggled to hold back his tears. After a moment, he glanced at her.

She attempted a grave look of disapproval, but her kind heart exhumed a sorrowful smile instead. Reassured, he said, “I did feel a little guilty when I thought of how my parents would’ve reacted. I actually imagined I felt my father’s hand on my shoulder, urging me to return to the store, and that’s what I did, redirected not so much by guilt, but by the security guard who was the owner of the hand on my shoulder.”

Lisa had to bite her lip to prevent from smiling. She liked his sense of humor and use of the language, which was unusual for a fourteen-year-old, and unique for a delinquent.

“What have you learned from this experience?”

“Don’t try to look nonchalant when you’re stealing. Just grab what you want, and run your ass off.”

Lisa gave him a stern stare to convey her disapproval. He smiled.

“The police have offered you an option called juvenile diversion, which allows you to bypass the courts and do community service to pay for your crime. I’ve spoken to them and to the store manager, and we’ve agreed that one hundred hours is a just penalty. Is this a problem for you?”

“Do I get to keep the glove?”

“Please take this seriously, Mr. Owens,” she chided. “You joke and act as if this doesn’t bother you, but I can see it does. I know you have good in you, otherwise you wouldn’t have helped the Sandersons.” She took a sip of her coffee. “I’m tempted to move you to a new foster home since your current foster parents don’t seem to be doing well by you, and you’ve gotten in with some bad company. I have a good couple in mind. They live near me in Kilworth, which would help me keep an eye on you, too. What would you think of moving out there?”

“Fine by me.”

“Okay. I’ll set up a move right away. So, for your hundred hours, you can help at various places like hospitals, the food bank, or the Y. Do you have any preference at all?”

“Towel boy in the girls’ locker room?”

“Uh, no. The food bank needs help now. I’ll put you there. Okay?” She typed something into her computer, printed out a sheet, and said, “Look this over and sign it if you agree to do your community service.” She handed him a pen, one that she’d had in her mouth a moment before. He looked askance at her, and she said, “Sorry, I guess I’m an oral personality. I can find another one.”

“No, that’s okay,” he said as he signed the document. “But if you were an anal personality, I would’ve insisted on it.” She laughed.

She gave him a brochure about the food bank. “I’ll meet you at the address shown on the front of this pamphlet at nine o’clock on Saturday morning. I’ll introduce you to the director, and he’ll tell you what he wants you to do. Go home and pack. I’ll pick you up tomorrow morning and take you to your new foster home.”

She put him with the best foster parents available and kept close tabs to ensure nothing else went wrong with this sad case.

•

So it was that in the middle of eighth grade, our protagonist moved to his final foster home. With him, he brought an old steamer trunk that his dad had bought secondhand to use as a combination liquor cabinet and coffee table in his dorm room at Berkeley. In that black trunk was everything Robert owned: a few tatty articles of clothing, a child’s baseball mitt and bat, and a few irreplaceable keepsakes from his former life. He had kept only what his mother, father, and sister had treasured most in life: his mother’s wedding and engagement rings, love letters from her husband, Olympic bronze medal and VCR tape of her figure skating performance that had earned her the medal; his father’s wedding ring, baseball jersey, and Air Force wings; his sister’s favorite blanket. He also kept family pictures, home movies, and a newspaper account of their death.

He took out his clothes and put them in the dresser, then placed the trunk at the foot of his bed. But he seldom opened it. It was still too painful.

Gunnar and Elspeth Krieger, two hefty German ex-patriots who looked just like each other, were the new foster parents. They had no love to give him—but, then, that would be expecting too much. They saw to it he was housed, clothed, and fed. They let him come and go as he pleased, just asking to be kept informed as to his whereabouts. The sole knock against them was they were miserly. Young Robert was fed mostly with bland, leftover hospital food that Elspeth brought home from her job as a cook at the university hospital. They gave him a twenty-five-dollar monthly allowance for all needs beyond food and shelter, so his clothes were Salvation Army castoffs, and his hair grew down past his shoulders. He looked just like the waif he was.

The couple lived in Kilworth, a delightful little subdivision of detached homes set on rolling hills on the bucolic banks of the Thames River just west of London, Ontario. Kilworth is an upper-middle class neighborhood, although the Krieger house was situated in the least affluent part of the village, on a circle of starter houses at the top of the hill near the highway.