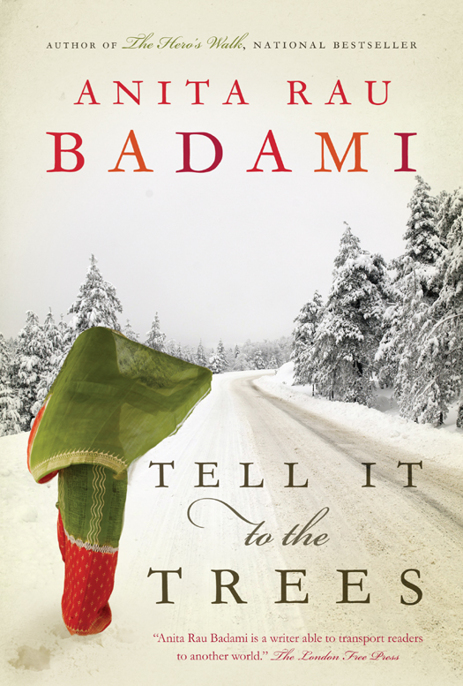

Tell It to the Trees

ALSO BY ANITA RAU BADAMI

Tamarind Mem

The Hero’s Walk

Can You Hear the Nightbird Call?

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright © 2011 Anita Rau Badami

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2011 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Badami, Anita Rau, [date]

Tell it to the trees / Anita Rau Badami.

Issued also in electronic format.

eISBN: 978-0-307-36674-0

I. Title.

PS

8553.A2845

T

44 2011

C

813′.54 C2011-901719-9

Cover design: Kelly Hill

Cover images: (woman in sari) © Wendy Webb Photography; (winter road) © Adam Radosavljevic /

Dreamstime.com

v3.1

For Madhav, my constant

Contents

Varsha

Suman

Varsha

Suman

Varsha

Suman

Varsha

Suman

Anu’s Notebook

Suman

Anu’s Notebook

Suman

Anu’s Notebook

Hemant

Anu’s Notebook

Hemant

Anu’s Notebook

Varsha

Anu’s Notebook

Hemant

Anu’s Notebook

Hemant

Anu’s Notebook

Varsha

Hemant

Suman

February 3, 1980

Sunday morning. Snow floats down like glitter dust from a flat winter sky, covering everything except Tree—dark against the overwhelming whiteness. The searchers have found her. Finally. She might have lain there, another anonymous mound, until spring, by which time she would have become a part of the softening earth as the snow melted in the slow warmth of the sun, if one of the search party had not noticed a pair of ravens cawing and pecking at something not too far from the house

.

Part One

VARSHA AND SUMAN

Varsha

One of the searchers spotted two ravens yanking at something and walked over to investigate. I watched as he squatted and peered down at the ground, raised his arm and waved the others over. They had found her.

The birds, they told us later, were tugging at her red and gold earring that was glinting up at them. We also heard she’d taken her jacket off even though it was thirty below that night. Sounds like a crazy thing to do, but I know it’s true. It’s what happens before you die from hypothermia, the blood vessels near the surface of your skin suddenly dilate making you think you are on fire and so you tear off your clothes to cool down. It’s quite a paradox really: the body starts to feel too hot before it dies of cold. But by that time your brain is hallucinating, creating images of longed-for warmth, making you believe all kinds of weird things. I think it would be right to assume she died happy, believing she was in the tropics, warm as toast.

She was lying not too far from our door, past the spot where in a few months, when all the snow has melted,

five rose bushes with bright pink flowers and giant thorns will mark the boundary between our land and old Mrs. Cooper’s. Several years ago, before she went off to live with her son in Vancouver, Mrs. Cooper sold her house to some developers who planned to turn it into a set of holiday homes, but it hasn’t happened yet. It’s shuttered and falling apart and I know ghosts live in it. I used to like hanging out in that whispering house, but some of the dumb boys from school discovered it and decided it was the perfect place to drink beer, smoke pot and giggle like fools and ruined it for me.

“Why on earth did she have to go out in such horrible weather?” my stepmother Suman asked for the nth time since the discovery of the body. She was stationed at the dining room window which provides almost as good a view as the one Hem and I had from the living room. “Didn’t she know how dangerous cold can be? Hanh? Do you know why she did such a thing?”

She looked

stricken

. That’s the word for it, the exact one. As if a giant hand had smacked the joy out of her. Not that she’s a very cheerful person to begin with, but for a while this summer she’d gone back to being the way she was when she first came to Merrit’s Point—young and happy. I almost feel sorry for her.

I shook my head. “We were asleep, Mama,” I said gently, again. “I’ve no idea why she had to go out. If I was awake maybe I could have stopped her.”

Beside me Hem pushed his small, warm body closer. I hugged him hard. Hemant is my half-brother, Suman’s

son, but entirely mine. I love him more than anything and anybody, more even than air and water and food, and just a bit more than Papa.

Out there things were winding down, the searchers loading the wrapped body onto a stretcher. We watched them carry it carefully to the waiting ambulance. An ambulance seemed kind of pointless since she was already dead, but people always hope for the best. Not me. I know that disaster lurks around every corner.

The ambulance churned away in a spray of snow and beside me Hem began to sob.

“Stop crying, you wuss,” I whispered, poking his cheek with my finger. He worries me sometimes. He is too much like Suman—no backbone, all emotion and weak. I have to make sure he doesn’t remain that way. For now, though, I can take it—he is only seven years old after all.

“I’m scared,” Hemant said. “I wish Akka was here.”

“Well she isn’t, is she?” I said, even though I too miss our grandmother. She’s in the hospital and not coming home. She’s too old and too sick.

“What will happen now?” Hem whispered.

“Nothing. They’ll take her to the morgue and a doctor will sign a certificate saying she’s dead, then Papa will notify her family. That’s all.” For the first time it occurred to me that she also had family. Just like us. A mother and brother and two nephews and a sister-in-law and cousins and aunts and uncles and maybe a grandma like Akka.

“What if they ask us questions?” Hem’s breath made a patch of mist on the windowpane.

“What if they do? We were asleep, how are we supposed to know what happened, you noodle? Now stop crying all over me, I’m here, nothing will happen to you.”

He pressed closer to me, wrapped both his arms around my waist and held me tight. I love the smell of him—milky and sweet. I am not a sentimental sort of girl, but with Hem I turn into everything I do not wish to be.

“Will you always be here with me, Vashi?” He gazed up at me with his big brown eyes that unfortunately always remind me of Suman. Like a puppy begging for love, for approval, soft and silly.

“Of course, where else would I be?”

“When you’re grown up also?”

“Well, I do plan to go away to university, Hem. But that isn’t for five whole years.”

“What if I feel like talking to someone when you’re away at university?” Hem asked anxiously.

“You’ll be a big boy by then—you won’t need me around so much,” I said.

“But I might still feel like talking to someone, then what?”

“You can always call me.”

“If you aren’t there?”

I knelt and wrapped my arms around him. “Talk to Tree, that’ll help, won’t it?” I felt his heart jumping against mine, in sync—

thump-thump-thump

—almost one. “Tree will always be here, Hem. It’s ours and it will never tell on us.”

I am Varsha Dharma, granddaughter of Mr. J.K. Dharma, late, and his wife Bhagirathi otherwise known as Akka. Daughter of Vikram and Harini (or Helen as my mother preferred to be called—she liked disguises). Stepdaughter to Suman, and sister to Hemant.

I am thirteen years old, almost fourteen. I love reading. I love my family. I prefer to have no friends. I plan to go to university. When I grow up I will be a lawyer. Maybe a writer. A scientist even. I can be anything I set my mind to be. I am super smart. Even Miss Frederick the English teacher who takes us for art as well and who is not fond of me concedes I am precocious beyond my years. She and the other teachers also feel I have an attitude issue—of course I do—and anger issues, according to reports they send to Papa citing complaints from the town mothers and their stupid children.

“Gene problem,” Akka says. “Like your father and his father. I am telling you, Varsha, learn to control that temper. Don’t turn into your Papa. Don’t turn bad like him.”