The 2012 Story (5 page)

Authors: John Major Jenkins

EXPLORERS AND LOST CITIES

Mexico was often accessed by travelers landing in Veracruz or Acapulco. But the Maya heartland lay far to the east, and the remnants of the ancient civilization of the Maya, more distantly remote in time than the Aztecs, were off the beaten path and had largely escaped the attention of travelers. Nevertheless, rumors of what lay hidden in the thick jungles of the east began reaching the ears of adventurers, including a colorful character named Count Waldeck.

Antonio Del Rio visited Palenque when it was very difficult to reach. He managed to publish his account in 1822, and to illustrate his book his London publisher hired a man named Jean-Frédéric Maximilien de Waldeck. An artist, traveler, and womanizer, Waldeck was so intrigued with Del Rio’s story of a lost city in the jungles of Mexico that, at age fixty-six, he crossed the ocean to see it for himself. While insinuating himself into society circles in Mexico City, doing portraits while seeking funds for his expedition to Palenque, Waldeck claimed to have been close friends with Lord Byron and Marie Antoinette. Eventually, the self-described count spent an entire year in the village of Santo Domingo near Palenque, plus four months in a hut he built in the shadows of Palenque’s crumbling tower. Joining him during his tenure studying the ruins was a young mestizo woman who probably provided some incentive for staying in that sweltering, bug-infested place. In these inhospitable circumstances he produced some ninety drawings, striking in their artful execution but deceiving in their embellished details.

After Palenque he went to the sites of Yucatán and made more drawings, escaping to London when he found out that the local authorities thought he was a spy. His drawings narrowly avoided being seized. Discovering that government officials were suspicious of his activities, he quickly copied the entire lot of drawings and let them seize the copies, while the originals were safely hidden away. His ruse made further searches of his belongings unnecessary. With his pictographic booty in hand, he published a selection of twenty-one plates with a hundred pages of text, in which he elaborated his theory that Palenque was built by Chaldeans and Hindus. Considering that no one had any clue as to when the Maya cities were built and lived in, Waldeck’s estimate for Palenque’s demise (600 AD) was surprisingly accurate. His book was immensely pricey, some $1,500 apiece in today’s dollars, apparently intended for nobles and counts like himself. Waldeck had accomplished what he set out to do, and he did it in his characteristic roguish style. For all we know, descendants of Waldeck are living in Palenque’s environs today.

By the late 1830s, many explorers had crisscrossed Anahuac (Mexico), looking for and finding evidence of many layers of ancient civilizations and fragments of a lost calendar. But for most outsiders—Europeans as well as people in the quickly expanding United States—Mexico and Central America were still seen as hot, disease-ridden, and uncivilized places best avoided. Two explorers were to change everything, and the world was ready to receive what they had to share.

In 1838, John Lloyd Stephens flipped through Waldeck’s book in Bart lett’s bookstore in New York City. Already a seasoned traveler at age thirty-two, having just written the critically acclaimed

Travels in Egypt and Arabia Petraea

(1837), Stephens was inspired, despite Waldeck’s reputation as an embellisher, to mount his own expedition to Central America. He invited a British acquaintance, artist Frederick Catherwood, to join him and document their findings. Their trip took place prior to photography becoming practical, but the detailed drawings Catherwood produced exceeded in quality anything produced by photography for another four decades.

Travels in Egypt and Arabia Petraea

(1837), Stephens was inspired, despite Waldeck’s reputation as an embellisher, to mount his own expedition to Central America. He invited a British acquaintance, artist Frederick Catherwood, to join him and document their findings. Their trip took place prior to photography becoming practical, but the detailed drawings Catherwood produced exceeded in quality anything produced by photography for another four decades.

Stephens had helped elect president Martin Van Buren, and through his office he secured an appointment: He would be U.S. Diplomatic Agent to the Republic of Central America. Despite the flimsy status of such a republic, his title and official-looking papers would help him navigate uncharted territories where governments rose and fell with the seasons. In October of 1839, they sailed from New York. Landing in Belize, they followed the reports of one Juan Galindo and ascended the Motagua River into Guatemala before turning south to cross a range of mountains, making a beeline for the rumored lost city that we now call Copán. Their trip was just beginning. Malaria, bandits, and civil wars were a constant threat, and would be over the next three months and 5,000 miles.

The sun barely pierced the heavy jungle canopy, but the oppressive heat of midday smothered everything. Three mules labored and slid on the muddy trail, burdened with packs, canvasses, and provisions. The two men patiently followed behind, swatting bugs while looking intently through the foliage, trying to spot the telltale signs of lost temples—an oddly placed stone, a cockeyed carving, rock walls hulking through the shadowy arboretum. On November 17, 1839, they entered Copán. Stephens later recalled, understating the surprise they really felt: “I am entering abruptly upon new ground.”

14

14

So began a new era in the exploration and recovery of the Maya civilization. After weeks of clearing away debris from temple stairways and platforms, Catherwood carefully making dozens of drawings, they realized they had barely scratched the surface. Stephens, realizing the importance of the site, purchased it from the rightful owner for $50. Anxious to get to Palenque, they set out across the mountains of Guatemala, down the Usumacinta River valley, and through the Lacandon rain forest, a journey of more than three hundred miles.

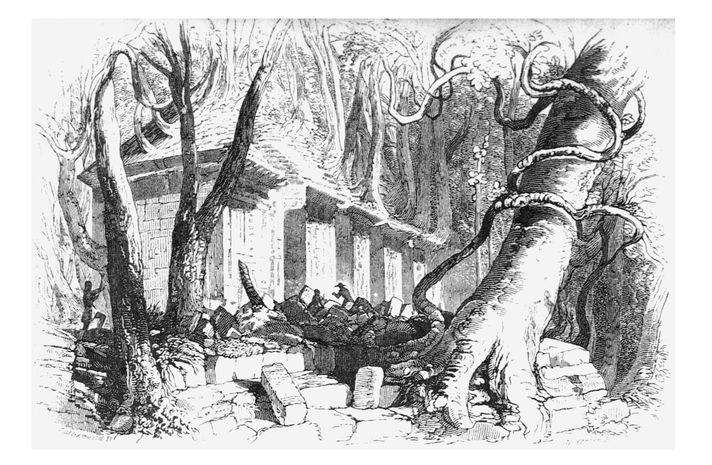

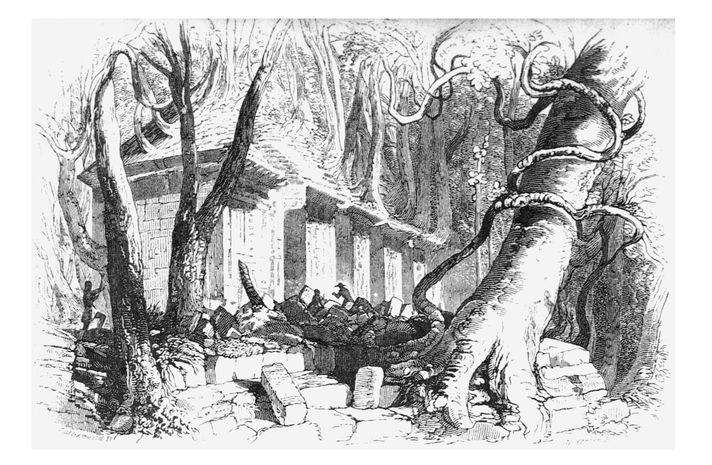

Palenque in 1840. Drawing by Frederick Catherwood

Arriving at Palenque, Stephens and Catherwood saw with their own eyes that Waldeck and Del Rio had not been exaggerating. By happenstance, another expedition, led by Walker and Caddy, had just visited and left Palenque. These kinds of close calls would occur time and again in the “discovery” of lost cities. Palenque, however, was never lost to the locals, although for centuries the stones languished half forgotten—and were often pillaged as a resource for good building stone.

Stephens and Catherwood continued their journey by visiting the extensive sites of the Yucatán peninsula. Labna, Uxmal, and the awe-inspiring site of Chichén Itzá topped their list of sites they explored and documented. From a man in Mérida Stephens learned about the dot and bar numeration that could be clearly seen in the glyphs. He could thus get a rudimentary handle on numerology in the Long Count dates, for a bar represented 5 and a dot represented 1. He duly reported these things in his engaging though somewhat dry travelogue, stoking the curiosity of many readers for years to come.

Incidents of Travel in Central America and Yucatan

, published and priced af fordably in 1841, was a huge success. It has remained in print to this day.

Incidents of Travel in Central America and Yucatan

, published and priced af fordably in 1841, was a huge success. It has remained in print to this day.

The realistic drawings by Catherwood were no doubt critical for helping outsiders understand the scope and scale of the lost civilization. Unfortunately, Catherwood’s name was left off the cover. It’s a sad and ironic fact that neither Stephens nor Catherwood lived long enough to see the era of scientific exploration they had spawned. Stephens died of liver disease at the age of forty-six in 1852. Catherwood drowned in a shipwreck in the Atlantic in 1854. By the 1860s, poor though compelling photographs were being made at the sites, providing undeniable proof that a lost civilization was buried in the jungles of Mexico. And other indications of an ancient high culture were emerging, in manuscripts discovered and published by an enterprising cleric who hid Atlantean theories under his ecclesiastical robe.

THE POPOL VUH APPEARSBorn in Holland in 1813, Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg spent his early years writing novels in Paris. He then went to Rome to study theology and was ordained for the priesthood. His eye, however, was always on Maya mysteries. Inspired by Stephens’s and Del Rio’s books, he set off for America in 1845. His ability to find forgotten manuscripts in moldy archives was uncanny. He located unpublished histories of New Spain penned by Las Casas and Durán, and an original history of the Aztecs written by Ixtlilxochitl. He spent several years in Mexico City and environs, learning the Nahuatl language, and thereafter traveled through Guatemala, El Salvador, as far as Nicaragua, looking for artifacts and manuscripts. In Guatemala he found

The Annals of the Cakchiquels

as well as Ximénez’s translation of

The Popol Vuh

stashed away in church archives.

The Annals of the Cakchiquels

as well as Ximénez’s translation of

The Popol Vuh

stashed away in church archives.

Returning to Paris in 1861, he published

The Popol Vuh

in a French translation. While there, he was given access to the Aubin collection of rare books and manuscripts from the Americas. Studying his own findings and the unparalleled Aubin collection, never before made available for perusal, de Bourbourg produced a four-volume study of Mesoamerican history and religion called

Histoire des Nations Civilisées du Mexique et de l’Amérique Centrale

. It so impressed Spanish historians that they opened their own museum collections for his study. In the Archives of the Academy of History he found de Landa’s long-forgotten manuscript

Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán

. Brasseur quickly published it, recognizing it as a key to helping decipher the Maya script. He could now identify the glyphs for the 20 day-signs of the 260-day sacred calendar as well the month signs of the 365-day civil calendar, but as a Rosetta Stone de Landa’s ideas and misleading presentations proved maddening.

The Popol Vuh

in a French translation. While there, he was given access to the Aubin collection of rare books and manuscripts from the Americas. Studying his own findings and the unparalleled Aubin collection, never before made available for perusal, de Bourbourg produced a four-volume study of Mesoamerican history and religion called

Histoire des Nations Civilisées du Mexique et de l’Amérique Centrale

. It so impressed Spanish historians that they opened their own museum collections for his study. In the Archives of the Academy of History he found de Landa’s long-forgotten manuscript

Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán

. Brasseur quickly published it, recognizing it as a key to helping decipher the Maya script. He could now identify the glyphs for the 20 day-signs of the 260-day sacred calendar as well the month signs of the 365-day civil calendar, but as a Rosetta Stone de Landa’s ideas and misleading presentations proved maddening.

As if these accomplishments in bringing to light lost books weren’t enough, Brasseur befriended a descendant of Hernan Cortés in Madrid and in 1864 was shown what became known as the Madrid Codex—an original Maya book from Yucatán containing astronomical almanacs and bewildering arrays of glyphs, gods, and calendar dates. It was an inscrutable text in which Brasseur nevertheless claimed to see many things. Following Alexander von Humbolt’s earlier belief that primitive contemporary cultures were fragments of an older high civilization destroyed by natural catastrophes, Brasseur came to believe that Egypt and Central America were rooted in the same cultural origin, and at other times migrations were caused by comets, meteors, and geological disruptions having celestial origins. The flood myths he encountered were seen to be evidence for cataclysms in ancient times, and he described them as an early rendition of the Atlantis myth, soon to be made popular by Ignatius Donnelly’s

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

(1882).

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

(1882).

Brasseur de Bourbourg continued writing books, but his ideas on the origins of Mesoamerican cultures grew progressively less credible to his peers. By the time he wrote

Chronologie Historique des Mexicains

he firmly believed that the Aztec legend of Quetzalcoatl was connected with Plato’s myth of Atlantis. He elaborated the theme freely and asserted that in 10,500 BC a sequence of four cataclysms occurred and that human civilizations originated not in the Middle East but in a continent that once extended from Yucatán into the Atlantic Ocean. Having sunk beneath the waves in cataclysmic upheavals perhaps triggered by meteors, the remnants were the Canary Islands. Here we find the seed point for much Atlantean speculation and writing that is a constantly resurfacing theme in the treatment of Maya history.

Chronologie Historique des Mexicains

he firmly believed that the Aztec legend of Quetzalcoatl was connected with Plato’s myth of Atlantis. He elaborated the theme freely and asserted that in 10,500 BC a sequence of four cataclysms occurred and that human civilizations originated not in the Middle East but in a continent that once extended from Yucatán into the Atlantic Ocean. Having sunk beneath the waves in cataclysmic upheavals perhaps triggered by meteors, the remnants were the Canary Islands. Here we find the seed point for much Atlantean speculation and writing that is a constantly resurfacing theme in the treatment of Maya history.

Perhaps a grain of truth is preserved in the persistence of this Atlantis mythos. The Maya were indeed advanced in ways bizarre and difficult to fathom. They held metaphysically elegant and spiritually profound doctrines that the modern scientific mind-set in particular is ill-disposed to grasp. Did they achieve a kind of consciousness fundamentally different from modern consciousness, and might that consciousness in some way be called, with good reason, “Atlantean”? Certainly the topic has been distorted, used, and abused through the years, but its very persistence suggests that it would benefit from a reappraisal.

Brasseur’s critics, once his fans, observed his increasingly alienating interpretations with disappointment. His perspective grew more and more strange, such that serious scholars who had once deferred to him became less and less confident in his ideas. Brasseur, for his part, insinuated that his critics had not studied the traditions of the Americas enough and harbored Old World biases. World history, he insisted, would be incomplete if the documents of the New World were left out. Despite his fall from grace in the eyes of his contemporaries, he is remembered as single-handedly bringing to light many hidden and forgotten texts of great importance, earning him a place of respect in the annals of independent sleuth-scholarship. Many of Brasseur de Bourbourg’s insights have slipped into consensus with barely a mention of credit.

DR. LE PLONGEON RAISES THE CHAC MOOLThe curious career of Dr. Augustus Le Plongeon was passed over almost without comment by Michael Coe in his book

Breaking the Maya Code

. But of all the fascinating characters that have danced on the stage of Maya studies, he should receive top billing. Completely self-funded, the sheer commitment and effort of Le Plongeon to recover monstrous stone artifacts and explain their perplexing circumstances are amazing to consider.

Breaking the Maya Code

. But of all the fascinating characters that have danced on the stage of Maya studies, he should receive top billing. Completely self-funded, the sheer commitment and effort of Le Plongeon to recover monstrous stone artifacts and explain their perplexing circumstances are amazing to consider.

Other books

Poor Badger by K M Peyton

A Matter of Honor by Gimpel, Ann

Cold Case Affair by Loreth Anne White

Please Save Me (Siren Publishing Ménage Everlasting) by Becca Van

As I Am by Annalisa Grant

The Box Man by Abe, Kobo

Sheltering Dunes by Radclyffe

Sleeping with the Enemy's Daughter by Nadia Aidan

Nightwings by Robert Silverberg

Fine Lines - SA by Simon Beckett