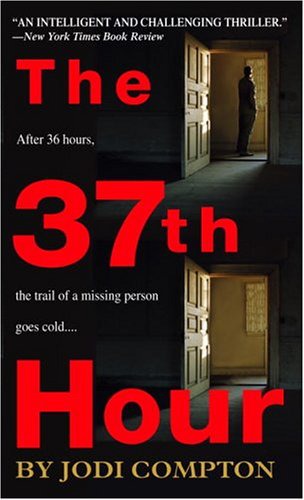

The 37th Hour

Authors: Jodi Compton

Tags: #Mystery, #Detective, #Mystery & Detective - Women Sleuths, #Minneapolis (Minn.), #Police, #Mystery & Detective, #Fiction - Mystery, #Mystery & Detective - General, #General, #Suspense, #Women Sleuths, #Thrillers, #Missing persons, #Fiction

Jodi Compton

Delacorte Press

table of contents

acknowledgments

This book is a work of fiction, with the usual amount of narrative license taken. Although real government agencies are named within, nothing here is meant to represent the actual workings of those agencies or their employees.

Having said that, there are several people who helped me understand the world in which Sarah Pribek works, and they deserve mentioning. Particularly I wish to thank an officer of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department and lawyers Beth Compton of Indiana and David Lillehaug of Minnesota. All remaining errors, or dramatic license taken, are to be laid at my doorstep, not theirs. Also helpful was reporter Carol Roberts of

The Tribune

in San Luis Obispo (when you retire, Carol, can I have that Rolodex?).

I also want to thank some extraordinarily supportive people in the publishing business: Barney et al. at the Karpfinger Agency, and Jackie and Nita at Bantam.

Lastly, I wish to thank my father for leaving thousands of crime novels around the house (fortunately not all at once) when I was growing up; my sister, whose opinion I seek first on story and character; and a teacher who learned me and a lot of other kids how to read. Thank you, Bethie.

chapter 1

Every cop has at least one story

about the day the job found them. It’s not uncommon. Out on the streets, on duty or off, suddenly an officer sees two guys in baseball caps and sunglasses run out of a bank as if their heels were afire. By pure luck, there’s an officer on the scene even before Dispatch takes the call.

With missing-persons cases, though, it’s a little different. The people you’re looking for, generally, are already dead, out of town, out of state, or in hiding. As a rule, they’re not in highly visible places, waiting for you to all but run into them. Ellie Bernhardt, fourteen, was to be the exception that proved the rule.

Yesterday, Ellie’s sister had come to see me, all the way to Minneapolis from Bemidji, in northwest Minnesota. Ainsley Carter was 21, maybe 22 at the outside. She was thin and had that tentative, nervous kind of beauty that seems proprietary to blondes, but today, and probably most days, she hadn’t chosen to accentuate her looks save for some dark-brown mascara and a little bit of concealer under the eyes that didn’t erase the shadow of a poorly slept night. She wore jeans and a softball shirt—the kind with a white body and colored long sleeves, blue in this case. A plain silver band rode her right hand; a very small diamond solitaire the left.

“I think my sister is probably in town somewhere,” she said, when I’d gotten her settled before my desk with a cup of coffee. “She didn’t come home from school the day before yesterday.”

“You contacted the police in Bemidji?”

“In Thief River Falls,” she said. “That’s where Ellie still lives, with our dad. My husband and I moved after we got married,” she explained. “So yes, they’re looking into it. But I think she’s here. I think she ran away from home.”

“Does she have a suitcase or bag that’s missing?”

Ainsley tipped her head to one side, thinking. “No, but her book bag is pretty large, and when I looked through her stuff I thought that some things were missing. Things that she wouldn’t take to school, but would want if she were leaving home.”

“Like?”

“Well, she had a picture of our mother,” Ainsley said. “Mom died about six years ago. Then I got married, and Joe and I moved away, so it’s just her and Dad.”

It seemed an anecdote was forming out of what had started to be generic background information, so I said nothing and let it unfold.

“Ellie had the usual amount of girlfriends growing up. She was a little shy, but she had friends. But just in the past year or so, I don’t know, Dad says they’ve kind of cooled off,” she said. “I think it’s just because Ellie has gotten so pretty. All of a sudden, within almost a year, she was tall, and she was developing, and she had such a lovely face. And that same year she was out of grade school and into junior high, and that’s a big change. I think maybe the girls felt differently about her, just like the guys did.”

“Guys?” I said.

“Since Ellie turned thirteen or so, boys have been calling. A lot of them are older boys, Dad says. It worries him.”

“Was Ellie seeing someone older, someone your father didn’t have a good feeling about?”

“No,” Ainsley said. “As far as he knew, she didn’t date at all. But I don’t have a good feel for her life.” She paused. “Dad’s nearly seventy. He doesn’t talk about girl things with us, he never has. So I can’t get a good idea from him what Ellie’s life is really like. I try to talk to her on the phone, but it’s not the same. I don’t think she has anyone to confide in.”

“Ainsley,” I said carefully, “when you talk to Ellie, when you visit the house, do you ever feel something isn’t right about her relationship with her father?”

She understood immediately what I was asking. “Oh, God, no,” she said, and her tone left me no room to doubt she meant it. She picked up her coffee; her blue eyes on me suggested she was waiting for another question.

I licked my teeth speculatively, tapped a pen against my notepad.

“What I hear you saying is that you worry because she doesn’t have any friends or nearby female relatives to talk to. Which is unfortunate, I guess, but what I don’t see here is a crisis that caused her to run away. Can you think of anything?”

“I did,” Ainsley said more slowly, “talk to her friends. Her classmates, I mean.”

“What did they say?”

“They didn’t say much. They were kind of embarrassed, and maybe feeling guilty. Ellie’s run away, and I’m her sister, and probably they felt like I was there to blame them for not being kinder or more supportive of her.”

“They didn’t say anything useful?” I prompted.

“Well,” she said, “one of the girls said there were some rumors.”

“What kind?” I asked.

“That Ellie was sexually active, I guess. I tried to get her to say more, but the other two girls jumped in, and said, ‘You know, people just talk.’ Something like that. I couldn’t get anything more out of them.”

I nodded. “But you said Ellie didn’t date. It seems like there wouldn’t be much grounds for those kinds of rumors.”

“Dad would let her go to sleepovers.” Ainsley lifted her coffee cup, didn’t drink. “He thought they were all-girls parties, but sometimes I wonder. You hear things, about what kids are doing at earlier and earlier ages. . . .” Her voice trailed off, leaving the difficult things unsaid.

“Okay,” I said. “None of this may be relevant at all to why she ran away.”

Ainsley went on with her train of thought. “I wish she could live with us,” she said. “I talked to Joe about it, but he says we don’t have enough room.” She twisted the diamond ring on her hand.

“Why do you think she’s in the Twin Cities?”

“She likes it here,” Ainsley said simply.

It was a good enough answer. Kids often ran away to the nearest metropolis. Cities seemed to promise a better life.

“Do you have a photo of Ellie I can use?”

“Sure,” she said. “I brought you one.”

The photo of Ellie did show a lovely girl, her hair a darker blond than her sister’s, and her eyes green instead of Ainsley’s blue. She had a dusting of kid freckles, and her face was bright but somewhat blank, as is often the case with school photos.

“It’s last year’s,” she said. “Her school says they just took class pictures, and the new one won’t be available for a week or so.” It was early October.

“Do you have another one that you can use?”

“Me?” she said.

“I have a full caseload right now,” I explained. “You, though, are free to look for Ellie full-time. You should keep looking.”

“I thought . . .” Ainsley looked a little disillusioned.

“I’m going to do everything I can,” I reassured her. “But you’re Ellie’s best advocate right now. Show her picture to everyone. Motel clerks, homeless people, the priests and ministers who run homeless shelters . . . anyone you think might have seen Ellie. Make color photocopies with a description and hang them up anywhere people will let you. Make this your full-time job.”

Ainsley Carter had understood me; she’d left to do what I’d said. But I found Ellie instead, and it was just dumb luck.

At midmorning the day after Ainsley’s visit, I’d driven out to a hotel in the outer suburbs. A clerk there had thought she’d seen a man and boy sought in a parental abduction, and I’d been asked to look into it.

I handled all kinds of crimes—all sheriff’s detectives did—but missing persons was a kind of subspecialty of my partner’s, and along the way, it had become mine, too.

The father and son in question were just packing up their old Ford van as I got there. The boy was about two years older and three inches taller than the one I was looking for. I was curious about why the boy wasn’t in school, but they explained they were driving back from a family funeral. I wished them safe driving and went back to the registration desk to thank the clerk for her civic-mindedness.

On the drive back, just before I got to the river, I saw a squad car pulled over between the road and the railroad tracks.

A uniformed officer stood by the car, looking south, almost as if she were guarding the tracks. Just beyond her, those tracks turned into a trestle across the river, and I saw the broad-shouldered form of another officer walking out onto it. It was a scene just odd enough to make me pull over.

“What’s going on?” I asked the patrolwoman when she approached my car. Sensing she was about to tell me to move along, I took my shield out of my jacket and flipped the holder open.

Her face relaxed a little from its hard-set position, but she didn’t take off or even push down her mirrored shades, so that I saw my own face in them, distended as if by a fish-eye lens. I read her nameplate:

OFFICER MOORE.

“I thought you looked familiar,” Moore said. Then, in answer to my question, she said succinctly, “Jumper.”

“Where?” I said. I saw Moore’s partner, now standing out on the train tracks mid-bridge, but no one else.

“She climbed down on the framework,” Moore said. “You can kind of see her from here. Just a kid, really.”

I craned my neck and did see a slender form on the webwork of the bridge, and then the flash of sunlight on dark-gold hair.