The Admiral and the Ambassador (36 page)

Read The Admiral and the Ambassador Online

Authors: Scott Martelle

Throughout the private and public wedding celebrations, Porter's conversations with his superiors in Washington about when he could come home, and the daily diplomatic distractions, Weiss's work crews continued their search. Parisians gathered daily at the site, sometimes joined by Porter, even though there was little for the public to seeâmost of the work was happening underground. On the surface, workers came and went, and loads of dirt were moved to the street and then loaded onto carts to be hauled away to the storage field. Journalists occasionally popped in, but the newspapers had little to show for it. In fact, the Parisian press largely ignored Porter's project, and reports from the American foreign correspondents rarely mentioned the dig.

Porter had left strict orders that he was to be summoned at the first sighting of any lead coffins, and on the afternoon of February 22, nearly three weeks after the first dirt was turned, Porter received the call. He hurried from the embassy to the excavation site, crawled down the ladder (probably Shaft A), and made his way to the discovery.

The location of the coffin was encouraging: it was near where the old steps descended from the gate between the orchard and the cemetery, meaning the grave could have been one of the last to be filled, which Porter had speculated would be the case for Jones's body. The condition of the coffin itself was discouraging. It was lead, but it had been heavily damagedâthe rounded “head” of the coffin had been sheared off, along with

the skull of the corpse. The damage was old, and Weiss's excavators also found the remnants of a wooden barrel at the head of the coffin. Porter and Weiss surmised it had been sunk below ground as a catch basin to hold runoff rain to water a garden, damaging the coffin as the barrel was sunk into place. With the coffin split open, its contents exposed to the subterranean moisture, worms, and bacteria, the decapitated remains had been reduced to rotted flesh on bones.

The lead coffin was buried inside a wooden casket, which bore a rusted copper nameplate “so brittle that when lifted it broke and a portion of it crumbled to pieces.” Working gingerly in the flickering candlelight, Porter tried to discern shadows of letters beneath the crusted green patina. None were legible. He carefully wrapped the shim of metal in his handkerchief, tucked it into a coat pocket, and climbed the ladder back out of the growing maze of tunnels. In his time in Paris, Porter had come to know the proprietor of M. André et Fil, an art-restoration business, and he headed there, where he asked the craftsman to work quickly but gently to uncover the name beneath the rust.

That night, Porter delivered a previously scheduled speech to the American Club in Paris and talked about his quest to find Jones's body. The tenor of the speech made it sound more political than historical, and it is hard to imagine that he was not counting on the foreign correspondents in attendance to wire his words to their newspapers back home. He detailed for the expatriate business leaders his efforts scouring records to find the cemetery in which Jones was likely buried, the more recent negotiations to obtain the right to dig for the body, and the need for Congress to approve the president's request to pay for the exhumation. Oddly, the

Washington Post

story on the speech did not mention that the dig had already begun, though that was clearly known both among the expatriates and the foreign correspondents. And it muddled the detail about the first shaft, implying that it had occurred a year before, at the onset of the negotiations with Crignier. If the money wasn't approved by Congress, the paper reported Porter as saying, the options would lapse and the opportunity would be lostâwhich was not the case.

“While other nations are gathering the ashes of their heroes in their Pantheons, their Valhallas, and their Westminster Abbeys, all that is mortal of this marvelous organizer of American victories upon the sea lies like an outcast in a squalid quarter of a distant city, in a neglected grave, where it was placed by the hand of charity to keep it from the potter's field,” Porter told his fellow Americans. “What once was consecrated ground is desecrated by vegetable gardens, a deposit for night soil, and even the burial of dogs. It is fitting that an effort be made to give him an appropriate sepulcher at last in the land of liberty which his efforts helped make free.”

6

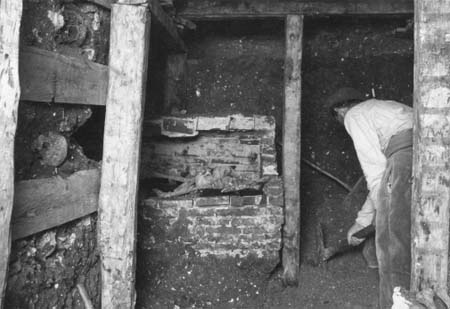

The search for John Paul Jones's body, during which workers made their way through layers of skeletons and large red worms, was not for those with weak stomachs. Note the skulls embedded in the earthen wall (left).

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Horace Porter Collection, Manuscript Division

Most of the news reports out of Paris focused on the found coffin and the likelihood that Jones was in it. Speculation turned to probability. The

New York Times

printed a two-paragraph story the next day reporting that “a metal casket, which is believed to contain the bones of John Paul Jones, has been found 16 feet below a grain shed at 14 Rue Grange aux Belles.” In addition to getting the address wrong, it said Porter and others involved with the dig believed the bones were Jones's; while they were hopeful, they in fact

had no basis to believe it was the right coffin and made no such claim. The story went on to say that the coffin would be opened the next dayâanother errorâand that the “time worn” nameplate was indecipherable.

7

But those weren't Porter's only problems with the media. From the beginning of the project, Porter had been concerned about intruders at the work site. When the lead coffin was found, he sent word to the prefect of police asking that two officers be assigned to watch over the site, particularly late at night through the early morning, when the workers were gone. “Late in the evening I learned that, owing to his absence from his office and an error in getting the communication to him, there would be no guard there that night,” Porter wrote later. “I could not help feeling some forebodings, and my state of mind may be imagined upon receiving a brief note early the next morning from an official saying he regretted to inform me that there had unfortunately been a depredation committed in the gallery where the leaden coffin was found.”

Porter hurried to the site feeling “like a person who had delayed a day too long in insuring his property and learned that it had taken fire.” But the damage, as it turned out, was minimal. “An enterprising reporter and photographer ⦠had succeeded in opening the gate, getting into the yard, and entering the gallery. In the darkness they had stumbled and broken their [camera] apparatus, and in trying to use one which our men had left in the gallery had broken it also.” Some camera pieces were missing, but otherwise the site was unscathed.

Porter received a report on the nameplate the next day from André, the art restorer, who had been able to work his magic on the severely damaged piece of metal. The front of the nameplate was beyond recovery, so he went to work on the reverse side, which had spent most of its time underground affixed to the wooden casket and thus was less rusted. Working carefully over two days, André cleared away the dirt and sufficient rust to read some of the engraved letters in reverse, enough to conclude that the coffin held the body of an Englishman who had died May 20, 1790, nearly two years before Jones. It was the wrong coffin, he told Porter.

By then, though, press accounts were swirling. “A reporter with a lively imagination could not wait for the deciphering of the plate and meanwhile invented a highly dramatic story,” Porter recalled later. A story appeared

saying “there was such certainty entertained that this leaden coffin contained the body of Paul Jones that I had summoned the personnel of the embassy and others to the scene, including the commissary of police who attended ornamented with his tricolored scarf.” The coffin was opened “with great ceremony and solemnity, and the group, deeply affected, stood reverently, with bowed heads, awaiting the recognition of the body of the illustrious sailor” before it became clear that “a serious error had been made.” None of that had happened, and it bothered Porter that the fictitious story had been printed. More importantly, people in some quarters believed the article, leading to criticism that the ambassador and his work crews didn't know what they were doing and were ready to conclude on the flimsiest evidence that they had succeeded.

8

The crews kept digging, but they had little to show for it beyond a deeper and more intricate maze of tunnels. Progress was slow. The area under the laundry was explored, but no other lead coffins were found. The terrain was dangerous and unstable and beleaguered by “infiltrations of water,” Weiss said, so “all the galleries were rapidly and carefully refilled and the work of exploring the property of the grain dealer begun.” The other three shafts were sunk and the galleries were then expanded below ground.

Finally, on March 23, a month after the first lead coffin was found, a crew digging near what had been the back wall of the cemetery discovered another wooden casket with a smaller lead coffin inside. This coffin had a well-preserved nameplate that identified the dead man as R

ICHARD

H

AY,

E

SQ.

, who had died in January 29, 1785. Not only was it not Jones, but Hay had been buried seven years before Jones, calling into question Porter's theory that the cemetery had been filled from the center outward. If Porter was disappointed or beginning to question the project, he didn't reveal it in any surviving records.

9

The crews worked on. Eight days later, they hit another lead coffin, this one within a few yards of the second discovered coffin, both near the foot of Shaft E, the last to be sunk. (No explanation could be found as to why it took so long to find the third coffin given its proximity to the second one.) It, too, had been encased in a wooden casket, but this one had suffered the ravages of a century underground. Little of the outer wooden casket was found beyond

rotted shards. A skeleton with no coffin of its own was lying atop the lead coffin, and the wooden lid was missing altogether, which meant there also was no nameplate. Workers sifted through the earth excavated from around the coffin but found nothing. Weiss supposed that the lid had been taken up and discarded at the time the coffin-less body had been buried. The workers pulled the coffin and exposed skeleton out of the earth, then carted the metal box to an open area in the gallery. Porter again was summoned.

The ambassador, looking at the crenulated metal, decided to open the lead coffin there underground, in part to dampen public speculation. The air was already so foul that Porter was persuaded to wait, fearing that the added odors from the open coffin would be overpowering in the close, dank space. Crews got to work extending the gallery to connect with a main tunnel emanating from Shaft A, on the opposite side of the cemetery. Once they were connected, this created a ventilation circuit, and the foul air improved considerably. It delayed the opening of the coffin for a week.

Finally, on April 7, Porter was alerted that the site was ready. He brought Bailly-Blanchard with him. Weiss was there too, as was a M. Géninet, Weiss's on-site supervisor for the project. The visitors all donned long smocks over their suits, and even deep below ground all but Weiss wore bowler hats. The workers took a break and gathered around as well, curious, all, as to what they would find.

The lead coffin had been placed atop a mound of dirt in a low-ceilinged gallery. The years and the weight of fifteen feet or so of earth had crumpled it so that the coffin looked like an elongated can crushed by giant hands. The original shape was still clear, though: narrow at the feet then broadening gradually to the shoulders before narrowing again to a rounded section for the head. There was a small solder plug sealing a hole near the head, and close by was a rough and jagged hole packed with darkened earth. It looked, Porter thought, as though it had been made by the end of a pickax, and he wondered if, sometime after the burial, someone had dug down and struck through the wooden top, piercing the lead coffin below. Maybe it was whoever had buried the skeleton found atop the coffin. There was a second hole in the coffin, too, a small crack near the foot, which Porter concluded had been caused by the shifting and settling of the earth from above. It, too, was packed with darkened dirt.

The coffin had been sealed shut before it was buried, and Porter was concerned that it be protected as much as possible from further damage. So the workers took their time removing the thin line of solder from the seam. When they finished, the top was carefully pried loose and lifted, filling the gallery with the smell of alcohol. There was no liquid, though. It had apparently evaporated slowly over time through the pickax hole and the crack at the feet, which the men decided accounted for the discolored earth in the holes.

The first thing the men saw was a packed layer of hay. After carefully removing a few handfuls, they found a body wrapped in a long linen burial sheet. More hay had been jammed between the corpse and the walls of the coffin, as though prepared for a long, bumpy journey. The packing was