Read The Adventure of English Online

Authors: Melvyn Bragg

The Adventure of English (29 page)

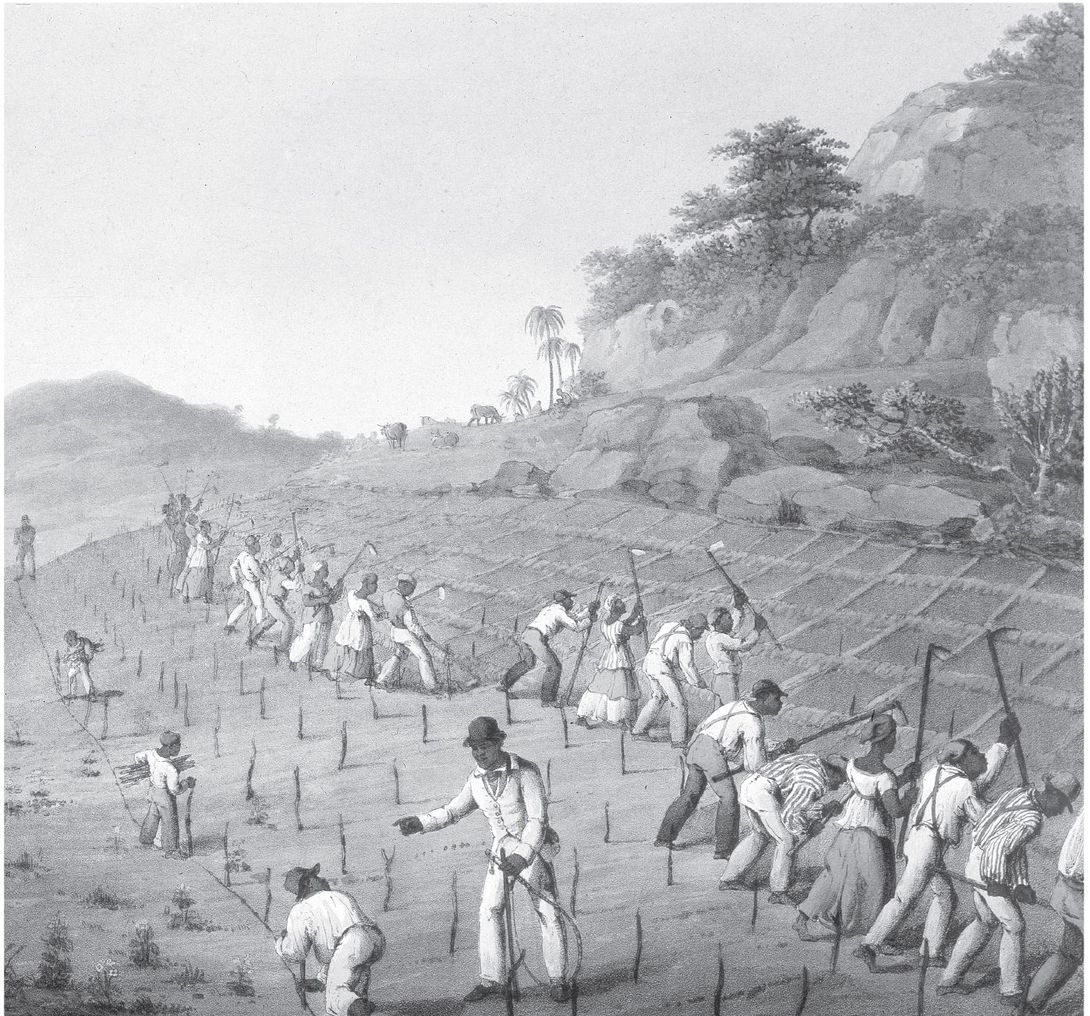

46. The first slaves who were brought over from Africa to work in the sugar plantations of the West Indies spoke many different African languages. Creoles developed as common languages in their own right.

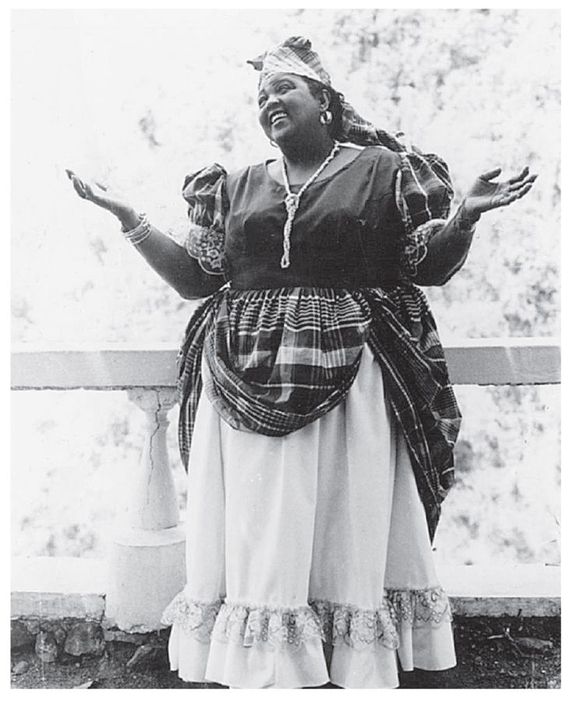

47. “Miss Lou” â Louise Bennett-Coverley, inspirational poet and champion of creole for over fifty years.

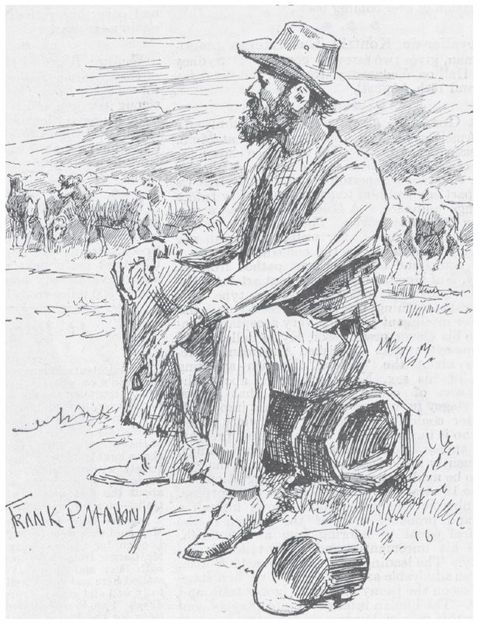

48. An illustration from

The Bulletin

(

below

), also known as

The Bushman's Bible,

which began weekly publication in 1880. One of the poems they printed was “Waltzing Matilda,” which became Australia's unofficial national anthem.

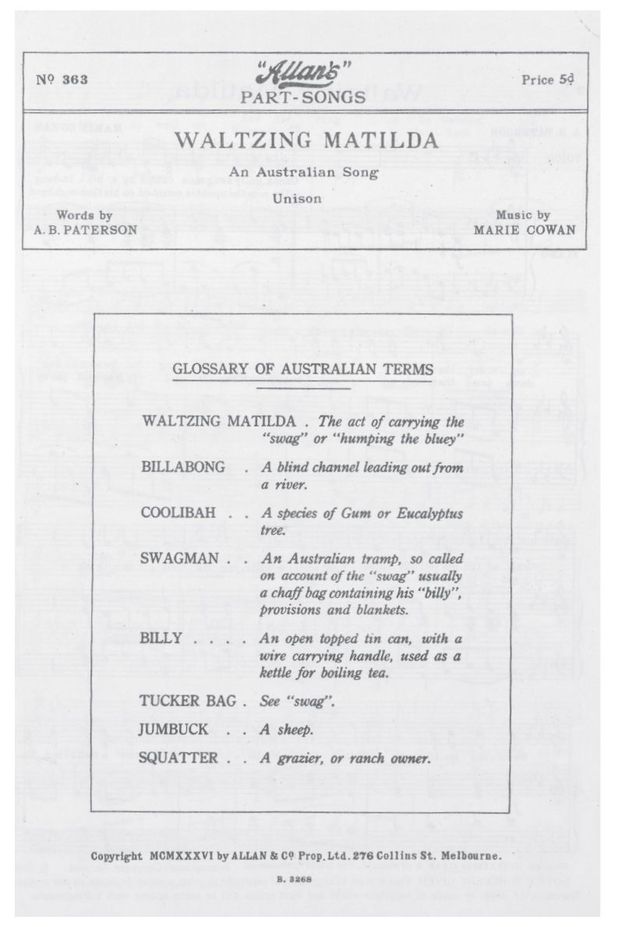

49. When the sheet music of “Waltzing Matilda” appeared in 1936, the publishers thought it necessary to print a glossary of the dialect used by its composer, “Banjo” Patterson.

50. In 1965,

Let Stalk Strine

was published to celebrate Australian and its pronunciation, but in the 1970s the

Macquarie Dictionary

was the first to officially embrace street and bush language.

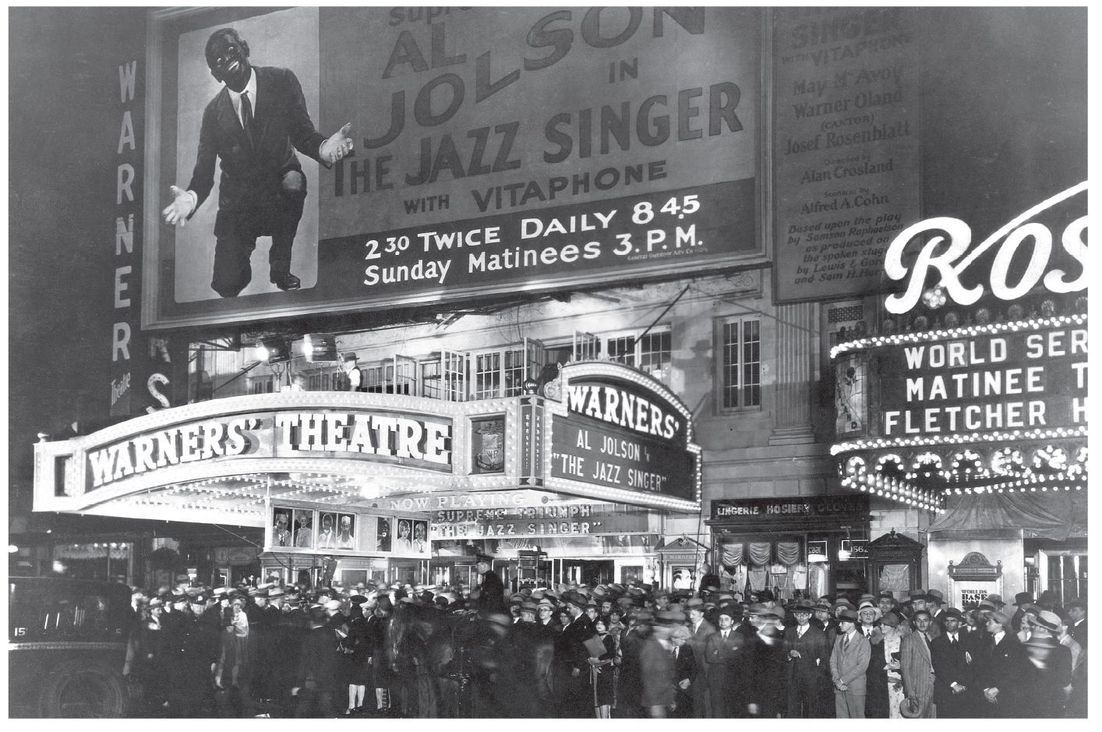

51. Crowds waiting to see

The Jazz Singer

in 1927: the “talkies” were fundamental in spreading American English around the globe.

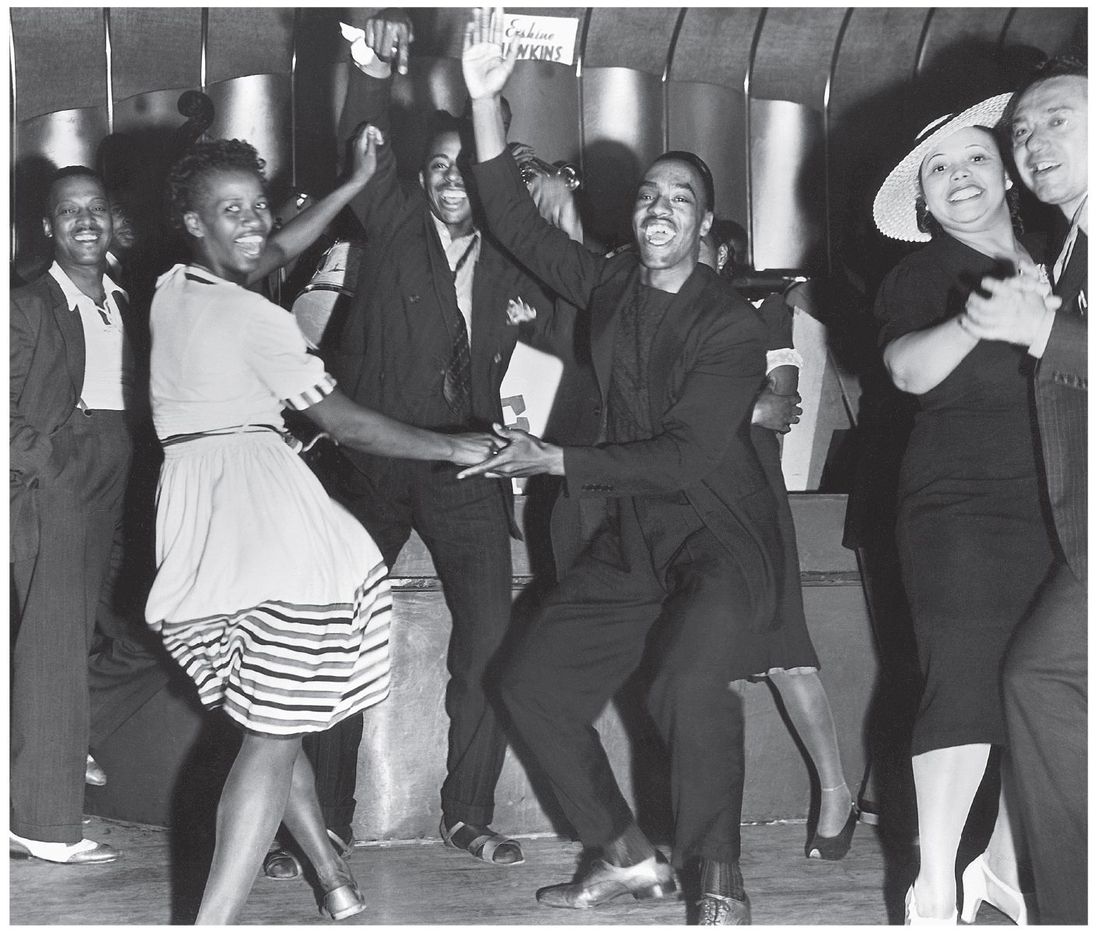

52. Jitterbugging, Harlem, mid 1930s: as African Americans moved north, their language and their music â jazz and blues â influenced English forever.

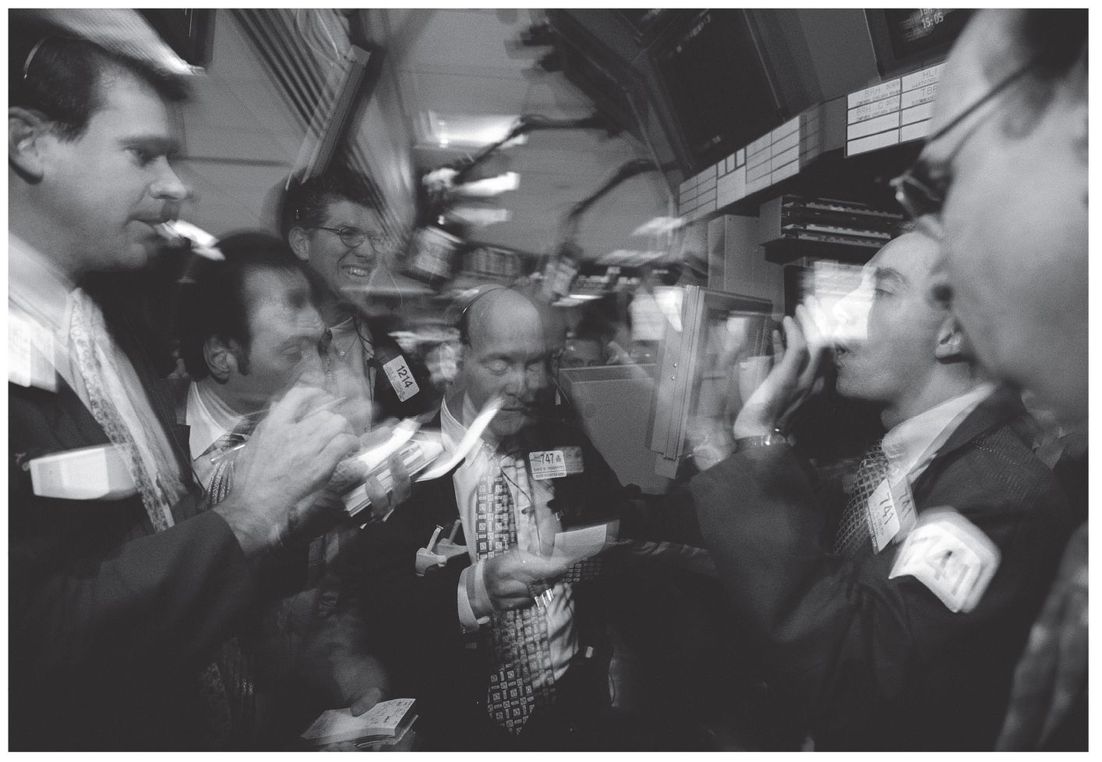

53. The New York Stock Exchange: English is the language of buyers and sellers, of crucial importance in worldwide commerce.

54. Singapore's popular cartoon character Mr. Kiasu speaks “Singlish,” an English dialect unique to Singapore. It borrows from the country's four official languages: Malay, Mandarin, Tamil and English.

55. A selection of the new words included in the latest edition of the

Oxford English Dictionary.

English went back to Latin and Greek in many of its descriptions of the new, often via the French: “oxygen,” “protein,” “nuclear” and “vaccine” did not exist in the classical languages but their roots are there. Some did come straight from Latin, in the nineteenth century, like “cognomen,” “opus,” “ego,” “sanatorium,” “aquarium,” “referendum” and “myth”; or from Greek, such as “pylon.” It was considered good practice to use parts of the classical languages: for example, anthropo-, or bio-, neo-, poly-, tele- as prefixes; or, as suffixes, -glot, -gram, -logy, -morphy. A great number of words found a use for the ending -ize.

Part of the fun of invention was to find the name. It is interesting how very few times a proper name was used â compared with, say, the British frontiersmen in the American west who freckled the landscape with names from wives, pals, relations, and names from the old country. Scientists, either through diffidence or wishing to claim a distinction for their discipline which matched anything in antiquity, tended to root around in the past. So when John Arnold made his Chronometer Number Thirty-Six (as blank a title as anything in Bach), it would once have been called a “timekeeper.” But together with the Hydrographer of the Navy, Alexander Dalrymple, he reinvented “chronometer” (dormant for about a hundred fifty years) from “chronos,” meaning time, and “metron,” a measure.

It has been estimated that between 1750 and 1900 half the world's published papers on mechanical, industrial and scientific advances were written and distributed in English. When James Watt needed to pursue his work in mathematics he had to learn and read French and Italian. Now English was the key tongue. Steam technology had revolutionised printing and so information could spread faster and further â telegraphy and telephony â than ever before. Moreover, the language became a magnet for European scientists who came west, to Britain, to pursue their work: the language delivered, among others, Marconi from Italy, Siemens from Prussia and Marc Isambard Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, from France. In the first part of the nineteenth century these small islands had become the world's leading trading and industrial nation, “the workshop of the world,” and the language, built over centuries, supple in all the arts of absorbing, stealing, inventing and restructuring, had matched the economic explosion. The expanded English language, a product of the Industrial Revolution, became an engine which drove it forward.