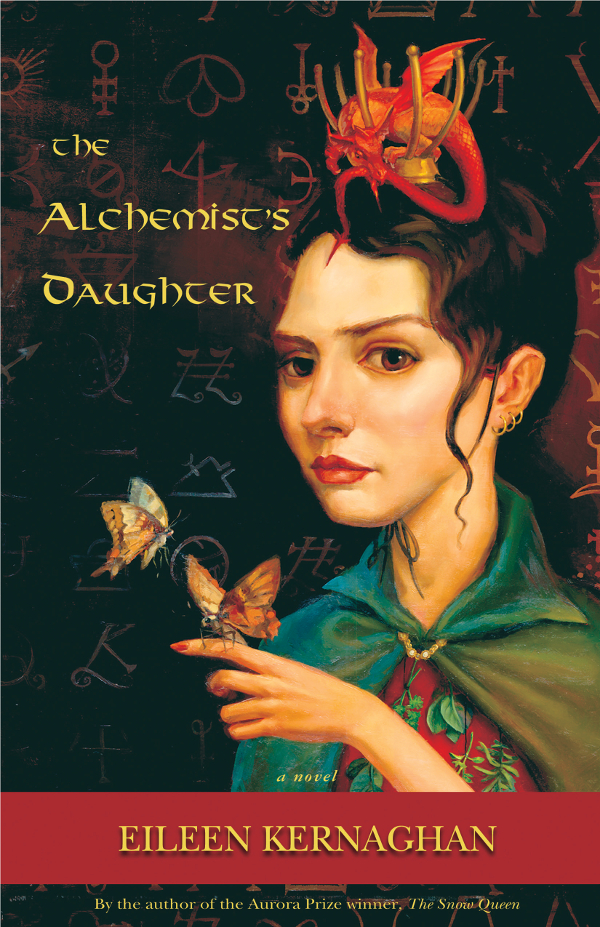

The Alchemist's Daughter

The

Alchemist's Daughter

The

Alchemist's Daughter

E

ILEEN KERNAGHAN

© 2004 by Eileen Kernaghan

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kernaghan, Eileen

The alchemist's daughter / written by Eileen Kernaghan.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-894345-79-8 (pbk.).âISBN 978-1-77187-040-5 (html).â

ISBN 978-1-77187-041-2 (pdf)

I. Title.

PS8571.E695A64 2004Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C813'.54Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C2004-904338-2

Cover painting:

The Alchemist

, by Lori Koefoed

Author photo: Diane Jarvis Jones

Cover and book design by Jackie Forrie

Printed and bound in Canada

Thistledown Press Ltd.

410 2nd Avenue North

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7K 2C3

www.thistledownpress.com

Thistledown Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing program.

The

Alchemist's Daughter

This one is for Christopher

CONTENTS

Charing Cross, 1587

Post mille exactos a partu virginis annos

Et post quingentos rursus ab orbe datos

Octavagesimus octavus mirabilis annus

Ingruet et secum tristitia satis trahet.

Sidonie put down her father's battered copy of Regiomontanus, by all accounts the greatest mathematician-astronomer of his time.

Octavagesimus octavus mirabilis

annus

: “the extraordinary eighty-eighth year”. Regiomontanus spoke of fifteen hundred and eighty-eight years after Christ's birth â a year when ill-omen was written in the stars.

There would be eclipses of both sun and moon, while Saturn, Jupiter and Mars would hang in conjunction with the moon's house. All this to Regiomontanus, writing in the previous century, had signalled catastrophe. Other scholars, examining his findings, could find no error in them. And then there was the rumoured marble slab, discovered in the ruins of Glastonbury, on which, inexplicably, Regiomontanus's words were carved. His prophecy had ended thus:

Cuncta tamen mundi sursum ibunt

atque decrescent/Imperia et luctus undique grandis erit

: “yet will the whole world suffer upheavals, empires will dwindle and everywhere will be great lamentations.”

Though her father had spoken often enough of that dire prognostication, until now Sidonie had not thought much about it. With thieves and beggars wandering the roads, talk of conspiracies in every inn and ale-house, and the constant threat of pox and plague, there was reason enough for lamentation in the land. And yet, while wars raged across Europe, England remained withal a blessed haven of peace.

But now this year was halfway done, and 1588 was all too near at hand.

Magic has power to experience and fathom things which

are inaccessible to human reason. For magic is a great secret

wisdom, just as reason is a great public folly.

â Paracelsus

As Sidonie came through the gate she met their maid-of-all-work Alys stumbling out of the house with her apron clutched across her face.

“Alys, whatever ails you?”

Alys glared accusingly at Sidonie over her apron hem.

“'Struth, mistress, the reek in that house is more than any mortal can abide.”

“Oh dear,” said Sidonie. “Another of Father's experiments?”

“Experiment, indeed. Wizardry, more like. And if he wants any dinner tonight, he can cook it himself.”

In the shuttered laboratory, the usual odours of sulphur and charred wood, candle-wax and musty books were overwhelmed by the stench of something moistly rotting.

“Merciful heavens, Father,” said Sidonie, clapping her hand over her nose, “what is making such a stink?”

“Stink, my child?” Her father glanced up abstractedly from his worktable. “Perhaps it is that basket of herbs that Alys brought in from the garden.”

Sidonie looked over his shoulder at the clutter of flasks and crucibles strewn across the table. She had no trouble finding the source of the smell. “Oh, Father, surely not again?”

Her father gazed sadly at the black, slimy mess clinging to the bottom and sides of an alembic.

“'Tis a great pity, daughter,” he said. “This time, I was as close as that to succeeding.” He held up his thumb and forefinger, a fraction of an inch apart.

“In playing God, you mean? And which recipe did you follow this time?”

“Why, Paracelsus, to the very letter,” said her father. Far from abashed, he seemed pleased at her interest. “One places the seed in a sealed retort, then buries it for forty days in horse dung, along with four magnets in the shape of a cross . . . ”

“It is no mystery, then,” interrupted Sidonie, “why Alys has fled in disgust, and why the house will need airing for a fortnight.”

Simon Quince took off his spectacles, which had rubbed a sore place on his nose, and set them carefully on the table. He peered up at Sidonie. “Why, what has become of Alys?”

“Gone, Father,” said Sidonie with exaggerated patience. “Driven away, like all the others.”

“These servants,” said Simon Quince, “pay them a queen's ransom, and yet they have no steadfastness, no loyalty.”

“No,” said Sidonie tartly, “but unfortunately they all have noses.” Then, curious in spite of herself, she said, “Go on, Father. What happens after forty days?”

“Why then, the homunculus begins to resemble a tiny human form. It breathes and moves, though it is without eyes, and transparent as jelly. Now, one feeds it daily with one's own blood, which carries the

pneuma

, the soul-substance, and keeps it at the steady temperature of a mare's womb. At the end of forty weeks it will have become as a human child in miniature.”

“I fear,” said Sidonie, eyeing the mess in the retort, “that somewhere you have missed out a step.”

“Alas,” said Simon Quince, his long, lined scholar's face the picture of melancholy, “when one explores the Secret of All Secrets, there are a great many opportunities for missteps. Still, this is how the Great Work must ever begin, with darkness, dissolution, formlessness. And one day, as God is my witness, I will succeed, and then my name will be spoken in one breath with the names of Paracelsus, and Flamel, and Dr. John Dee.”

“And then perchance we will be able to keep a servant,” muttered Sidonie, as she threw back the shutters to let in the cool herb-scented summer night.

Oh Lady Fortune,

Stand you auspicious!

â William Shakespeare,

The Winter's Tale

“Daughter!”

Sidonie laid a ribbon in her Euclid to mark the page and gave the soup kettle another stir. “Yes, Father?”

“Did I tell you that Thomas has also abandoned us, hired away by that mountebank Fletcher?”

“That mountebank Fletcher is much in favour at court,” Sidonie reminded him.

“Only because Dr. Dee is travelling abroad, and the lords and ladies insist upon their entertainments.”

“Then shall I write out an advertisement for a scryer?” Sidonie asked. “You must dictate, I do not know what you wish to say â beyond âmust be willing to work any hour of the day or night, for tuppence a fortnight'.”

“Nay, child,” said Quince, ignoring this piece of impudence. “I have not time for that. Every vagabond and street juggler in the city will be lined up at our door. I had another thought, just now. Leave off what you're doing, I pray you, and come hear me out.”

Reluctantly, Sidonie put down her book. She did not like the sound of this.

As always, when her father seized upon a fresh enthusiasm, his gaunt features softened, became almost boyish. “Sidonie, we've always known that you possess the gift.”

“No, Father, I have told you . . . ”

Sidonie's hasty protest was cut short.

“I know, my child, you have said that you want nothing

to do with sorcery. I do not speak of sorcery, only of scrying. To look into the crystal, to see the future, to discover what is hidden, that is a kind of science, is it not?”

“Not any kind of science I want to practise,” Sidonie

said. “Father, you know well enough why I will not scry. How can you ask such a thing of me?”

“Because,” Simon Quince said gently, “it seems to me wrong, to deny the talents your were born with. It saddens me to see you waste those talents in sweeping and stirring and making beds.”

“Then hire another servant,” Sidonie said.

“In truth, daughter, we can ill afford to pay a servant, let alone a scryer. And it is the scrying that keeps the wolf from our door. Things were different, when your mother was alive. And clearly you have inherited her gift.”

“Her curse, you mean,” Sidonie said bitterly.

“If you will. It became her curse. But it does not have to be so. Your mother looked into her mirror, Sidonie â that was her grave error. She looked into her mirror, and saw her own fate. That is more than any of us can bear.”