The Anatomy of Story (61 page)

Read The Anatomy of Story Online

Authors: John Truby

Let's look at the ideal sequence you should work through to construct

a great scene. Ask yourself the following questions:

1.

Position on the character arc:

Where does this scene fit within the hero's development (also known as the character arc), and how does it further that development?

2.

Problems:

What problems must be solved in the scene, or what must be accomplished?

3.

Strategy:

What strategy can be used to solve the problems?

4.

Desire:

Which character's desire will drive the scene? (This character may be the hero or some other character.) What does he want? This desire provides the spine of the scene.

5.

Endpoint.

How does that character's desire resolve? By knowing your endpoint in advance, you can focus the entire scene toward that point.

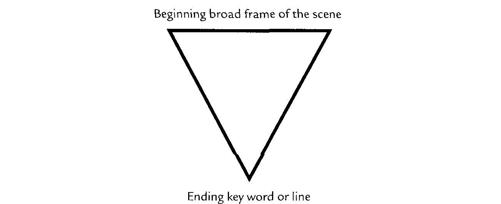

The endpoint of the desire also coincides with the point of the inverted triangle, where the most important word or line of the scene is positioned. This combination of the endpoint of the desire with the key word or line creates a knockout punch that also kicks the audience to the next scene.

6.

Opponent:

Figure out who opposes the desire and what the two (or more) characters fight about.

7.

Plan:

The character with the desire comes up with a plan to reach the goal. There are two kinds of plans that a character can use within a scene: direct and indirect.

In a direct plan, the character with the goal states directly what he wants. In an indirect plan, he pretends to want one thing while actually wanting something else. The opposing character will have one of two responses: he will recognize the deception and play along, or he will be fooled and end up giving the first character exactly what he really wants.

A simple rule of thumb can help you decide which sort of plan the character should use. A direct plan increases conflict and drives characters apart. An indirect plan decreases conflict initially and brings characters together, but it can cause greater conflict later on when the deception becomes clear.

Remember, the plan refers to how the character tries to reach a goal within the scene, not in the overall story.

8.

Conflict:

Make the conflict build to a breaking point or a solution.

9.

Twist or reveal:

Occasionally, the characters or the audience (or both) are surprised by what happens in the scene. Or one character tells another off. This is a kind of self-revelation moment in a scene, but it is not final and may even be wrong.

Note that many writers, in an attempt to be "realistic," start the scene early and build slowly toward the main conflict. This doesn't make the scene realistic; it makes it dull.

KEY POINT: Start the scene as late as possible without losing any of the key structure elements you need.

COMPLEX OR SUBTEXT SCENES

The classic definition of subtext is a scene where the characters don't say what they really want. This may be true, but it doesn't tell you how to write it.

The first thing to understand about subtext is that conventional wisdom is wrong: it's not always the best way to write the scene. Subtext characters are usually afraid, in pain, or simply embarrassed to say what they really think or want. If you want a scene with maximum conflict, don't use subtext. On the other hand, if it's right for your particular characters and the scene they are in, by all means use it.

A subtext scene is based on two structural elements: desire and plan. For maximum subtext, try these techniques:

■

Give

many

characters in the scene a hidden desire. These desires should be in direct conflict with one another. For example, A is secretly in love with B, but B is secretly in love with C. ■ Have all the characters with hidden desires use an indirect plan to get what they want. They say one thing while really wanting something else. They may be trying to fool the others, or they may use subterfuge they know is obvious but hope the artifice is charming enough to get them what they really want.

DIALOGUE

Once you've constructed the scene, you use description and dialogue to write it. The fine art of description is not within the scope of a book on story. But dialogue is.

Dialogue is among the most misunderstood of writing tools. One misconception has to do with dialogue's function in the story: most writers ask their dialogue to do the heavy lifting, the work that the story structure should do. The result is dialogue that sounds stilted, forced, and phony. But the most dangerous misconception about dialogue is the reverse

of asking it to do too much; it is the mistaken belief that good dialogue is real talk.

KEY POINT: Dialogue is not real talk; it is highly selective language that

sounds like it

could

be real.

KEY POINT: Good dialogue is always more intelligent; wittier, more

metaphorical, and better argued than in real life.

Even the least intelligent or uneducated character speaks at the highest level at which that person is capable. Even when a character is wrong, he is wrong more eloquently than in real life.

Like symbol, dialogue is a technique of the small. When layered on top of structure, character, theme, story world, symbol, plot, and scene weave, it is the subtlest of the storyteller's tools. But it also packs tremendous punch.

Dialogue is best understood as a form of music. Like music, dialogue is communication with rhythm and tone. Also like music, dialogue is best when it blends a number of "tracks" at once. The problem most writers have is that they write their dialogue on only one track, the "melody." This is dialogue that explains what is happening in the story. One-track dialogue is a mark of mediocre writing.

Great dialogue is not a melody but a symphony, happening on three major tracks simultaneously. The three tracks are story dialogue, moral dialogue, and key words or phrases.

Track 1: Story Dialogue—Melody

Story dialogue, like melody in music, is the story expressed through talk. It is talk about what the characters are doing. We tend to think of dialogue as being opposed to action: "Actions speak louder than words," we say. But talk is a form of action. We use story dialogue when characters talk about the main action line. And dialogue can even carry the story, at least for short periods of time.

You write story dialogue the same way you construct a scene:

■ Character 1, who is the lead character of the scene (and not necessarily the hero of the story), states his desire. As the writer, you should know the endpoint of that desire, because this gives you the line on which the dialogue of the scene (the spine) will hang.

■ Character 2 speaks against the desire.

■ Character 1 responds with dialogue that uses a direct or indirect plan to get what he wants.

■ Conversation between the two becomes more heated as the scene progresses, ending with some final words of anger or resolution.

An advanced dialogue technique is to have the scene progress from dialogue about action to dialogue about being. Or to put it another way, it goes from dialogue about what the characters are doing to dialogue about who the characters really are. When the scene reaches the hottest point, one of the characters says some form of the words "You are .. ." He then gives details of what he thinks about the other person, such as "You are a liar" or "You are a no-good, sleazy . . ." or "You are a winner."

Notice that this shift immediately deepens the scene because the characters are suddenly talking about how their actions define who they essentially are as human beings. The character making the claim "You are ..." is not necessarily right. But just the simple statement makes the audience sum up what they think of these characters so far in the story. This technique is a kind of self-revelation within the scene, and it often includes talk about values (see Track 2, moral dialogue). This shift from action to being is not present in most scenes, but it is usually present in key scenes. Let's look at an example of this shift in a scene from

The Verdict.

The Verdict

(novel by Barry C. Reed, 1980; screenplay by David Mamet, 1982)

In this scene, Mr. Doneghy, brother-in-law of the victim, accosts attorney Frank Galvin for turning down a settlement offer without consulting him first. We come in about halfway through the scene:

INT. COURTHOUSE CORRIDOR DAY

DONEGHY

. . . Four years ... my wife's been crying to sleep what they, what, what they did to her sister.

CALVIN

I

swear

to you I wouldn't have turned the offer down unless I thought I could win the case . . .

DONEGHY

What you

thought?

What you

thought. . .

I

'm a working

man,

I'm trying to get my wife out of

town,

we

hired

you, we're

paying

you, I got to find out from the other

side

they offered two hundred . . .

GALVIN

I'm going to win this

case . . .

Mist. . . Mr. Doneghy . . . I'm going to the jury with a solid case, a

famous

doctor as an

expert

witness, and I'm going to win eight hundred thousand dollars.

DONEGHY

You guys, you guys, you're all the same. The doctors at the

hospital, you .

. . it's "What I'm going to do for you"; but you screw up it's "We did the best that we could.

I

'm dreadfully sorry . . ." And people like me live with your mistakes the rest of our lives.

Track 2: Moral Dialogue—Harmony

Moral dialogue is talk about right and wrong action, and about values, or what makes a valuable life. Its equivalent in music is harmony, in that it provides depth, texture, and scope to the melody line. In other words, moral dialogue is not about story events. It's about the characters' attitudes toward those events.

Here's the sequence in moral dialogue:

■ Character 1 proposes or takes a course of action.

■ Character 2 opposes that action on the grounds that it is hurting someone.

■

The scene continues as each attacks and defends, with each giving

reasons to support his position.

During moral dialogue, characters invariably express their values, their likes or dislikes. Remember, a character's values are actually expressions of a deeper vision of the right way to live. Moral dialogue allows you, at the most advanced level, to compare in argument not just two or more actions but two or more ways of life.

Track 3: KeyWords, Phrases, Taglines, and Sounds-Repetition, Variation, and Leitmotif

Key words, phrases, taglines, and sounds are the third track of dialogue. These are words with the potential to carry special meaning, symbolically or thematically, the way a symphony uses certain instruments, such as the triangle, here and there for emphasis. The trick to building this meaning is to have your characters say the word many more times than normal. The repetition, especially in multiple contexts, has a cumulative effect on the audience.

A tagline is a single line of dialogue that you repeat many times over the course of the story. Every time you use it, it gains new meaning until it becomes a kind of signature line of the story. The tagline is primarily a technique for expressing theme. Some classic taglines are "Round up the usual suspects," "I stick my neck out for nobody," and "Here's looking at you, kid," from

Casablanca.

From

Cool Hand Luke:

"What we've got here is failure to communicate." From

Star Wars:

"May the Force be with you." From

Field of Dreams:

"If you build it, he will come."

The Godfather

uses two taglines: "I'll make him an offer he can't refuse" and "It's not personal; it's business."