The Anatomy of Story (7 page)

Read The Anatomy of Story Online

Authors: John Truby

Toots ie

(by Larry Gelbart and Murray Schisgal, story by Don McGuirc and Larry Gelbart, 1982)

■ Premise

When an actor can't get work, he disguises himself as a woman and gets a role in a TV series, only to fall in love with one of the female members of the cast.

■ Possibilities

You could take a funny look at the modern dating dance, but also dissect the deep immorality that underlies how men and women act toward each other in the most intimate part of their lives.

■ Story Challenges

How do you show the effect of men's immoral actions against women without seeming to attack one entire gender while making the other gender look innocent?

■ Problems

How do you make a man believable as a woman, weave several man-woman plots together and make them one, end each plotline successfully, and make an emotionally satisfying love story while using a number of farce techniques that place the audience in a superior position?

■ Designing Principle

Force a male chauvinist to live as a woman. Place the story in the entertainment world to make the disguise more believable.

■ Best Character

Michael's split between dressing as both a man and a woman can be a physical and comical expression of the extreme contradiction within his own character.

■ Conflict

Michael fights Julie, Ron, Les, and Sandy about love and honesty.

■ Basic Action

Male hero impersonates a woman.

■ Character Change

W— Michael is arrogant, a liar, and a womanizer. C—By pretending to be a woman, Michael learns to become a better man and capable of real love.

■ Moral Choice

Michael sacrifices his lucrative acting job and apologizes to Julie for lying to her.

T

HE GODFATHER

is a long, complex novel and film.

Toot-sie

is a highly choreographed whirl of unrequited love, mistaken identity, and farcical missteps.

Chinatown

is a tricky unfolding of surprises and revelations. These very different stories are all successful because of the unbreakable organic chain of seven key structure steps deep under each story's surface.

When we talk about the structure of a story, we talk about how a story develops over time. For example, all living things appear to grow in one continuous flow, but if we look closely, we can see certain steps, or stages, in that growth. The same is true of a story.

A story has a minimum of seven steps in its growth from beginning to end:

1. Weakness and need

2. Desire

3. Opponent

4. Plan

5. Battle

6. Self-revelation

7. New equilibrium

The seven steps are not arbitrarily imposed from without, the way a mechanical story structure such as three-act structure is. They exist

in

the story. These seven steps are the nucleus, the DNA, of your story and the foundation of your success as a storyteller because they are based on

human action.

They are the steps that any human being must work through to solve a life problem. And because the seven steps are organic—implied in your premise line—they must be linked properly for the story to have the greatest impact on the audience.

Let's look at what each of these steps means, how they are linked one to another below the surface, and how they actually work in stories.

1. WEAKNESS AND NEED

From the very beginning of the story, your hero has one or more great weaknesses that are holding him back. Something is missing within him that is so profound, it is ruining his life (I'm going to assume that the main character is male, simply because it's easier for me to write that way).

The need is what the hero must fulfill within himself in order to have a better life. It usually involves overcoming his weaknesses and changing, or growing, in some way.

Tootsie

■ Weaknesses

Michael is arrogant, selfish, and a liar.

■ Need

Michael has to overcome his arrogance toward women and to stop lying and using women to get what he wants.

The Silence of the Lambs

■ Weaknesses

Clarice is inexperienced, suffering from haunting childhood memories, and a woman in a man's world.

■ Need

Clarice must overcome the ghosts of her past and gain respect as a professional in a man's world.

I

can't

emphasize

enough how important the need is to your success. Need is the wellspring of the story and sets up every other step. So keep two critical points in mind when you create your hero's need.

KEY POINT: Your hero should not be aware of his need at the beginning of

the story.

If he is already cognizant of what he needs, the story is over. The hero should become aware of his need at the self-revelation, near the end of the story, only after having gone through a great deal of pain (in a drama) or struggle (in a comedy).

KEY POINT: Give your hero a moral need as well as a psychological need.

In average stories, the hero has only a psychological need. A psychological need involves overcoming a serious flaw that is hurting nobody but the hero.

In better stories, the hero has a moral need in addition to a psychological need. The hero must overcome a moral flaw and learn how to act properly toward other people. A character with a moral need is always hurting others in some way (his moral weakness) at the beginning of the story.

The Verdict

Frank's psychological need is to beat his drinking problem and regain his self-respect. His moral need is to stop using other people for money and learn to act with justice. We know Frank has a moral need when we see him lie his way into a funeral of strangers in order to get business. He doesn't care if he upsets the family. He just wants to make money off of them.

One reason it is so important to give your hero a moral as well as a psychological need is that it increases the scope of the character; the character's actions affect others besides him. This moves the audience in a more powerful way.

The other reason you want to give your hero a moral need is that it prevents him from being perfect or being a victim. Both of these are the kiss of death in storytelling. A perfect character doesn't seem real or believable.

When a character has no moral flaws, the opponent, who does, typically dominates the hero, and the story becomes reactive and predictable.

Also present from page one of your story, but much less important than weakness and need, is the problem. All good stories begin with a kick: the hero is already in trouble. The problem is the crisis the hero finds himself in from page one. He is very aware of the crisis but doesn't know how to solve it.

The problem is not one of the seven steps, but it's an aspect of weakness and need, and it is valuable. Crisis defines a character very quickly. It should be an outside manifestation of the hero's weakness. The crisis highlights that weakness for the audience and gives the story a fast start.

KEY POINT: Keep the problem simple and specific.

Sunset Boulevard

■ Weakness

Joe Gillis has a fondness for money and the finer things in life. He is willing to sacrifice his artistic and moral integrity for his personal comfort.

■ Problem

Joe is broke. A couple of guys from the finance company come to his apartment to repossess his car. He makes a run for it.

Tootsie

■ Weaknesses

Michael is arrogant, selfish, and a liar.

■ Problem

Michael is an excellent actor, but he's so overbearing that no one will hire him. So he's desperate.

SEVEN-STEPS TECHNIQUE: CREATING THE MORAL NEED

W

riters often think they have given their hero a moral need when it is just psychological. Remember the simple rule of thumb: to have a moral need, the character must be hurting at least one other person at the beginning of the story.

Two good ways to come up with the right moral need for your hero are to connect it to the psychological need and to turn a strength into a weakness. In good stories, the moral need usually comes out of the psychologi-

cal need. The character has a psychological weakness that leads him to take it out on others.

To give your character a moral as well as a psychological need and to make it the right one for your character,

1. Begin with the psychological weakness.

2. Figure out what kind of immoral action might naturally come out of that.

Identify the deep-seated moral weakness and need that are the source of this action.

A second technique for creating a good moral need is to push a strength so far that it becomes a weakness. The technique works like this:

1. Identify a virtue in your character. Then make him so passionate about it that it becomes oppressive.

2. Come up with a value the character believes in. Then find the negative version of that value.

2. DESIRE

Once the weakness and need have been decided, you must give the hero desire. Desire is what your hero wants in the story, his particular goal.

A story doesn't become interesting to the audience until the desire comes into play. Think of the desire as the story track that the audience "rides along." Everyone gets on the "train" with the hero, and they all go after the goal together. Desire is the driving force in the story, the line from which everything else hangs.

Desire is intimately connected to need. In most stories, when the hero accomplishes his goal, he also fulfills his need. Let's look at a simple example from nature. A lion is hungry and needs food (a physical need). He sees a herd of antelope go by and spots a young one that he wants (desire). If he can catch the little antelope, he won't be hungry anymore. End of story.

One of the biggest mistakes a writer can make is to confuse need and

desire or to think of them as a single step. They are in fact two unique story steps that form the beginning of your story, so you have to be clear about the function of each.

Need has to do with overcoming a weakness

within

the character. A hero with a need is always paralyzed in some way at the beginning of the story by his weakness. Desire is a goal

outside

the character. Once the hero comes up with his desire, he is moving in a particular direction and taking actions to reach his goal.

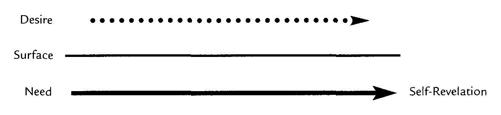

Need and desire also have different functions in relation to the audience. Need lets the audience see how the hero must change to have a better life. It is the key to the whole story, but it remains hidden, under the surface. Desire gives the audience something to want along with the hero, something they can all be moving toward through the various twists and turns—and even digressions—of the story. Desire is on the surface and is what the audience

thinks

the story is about. This can be shown schematically as follows: