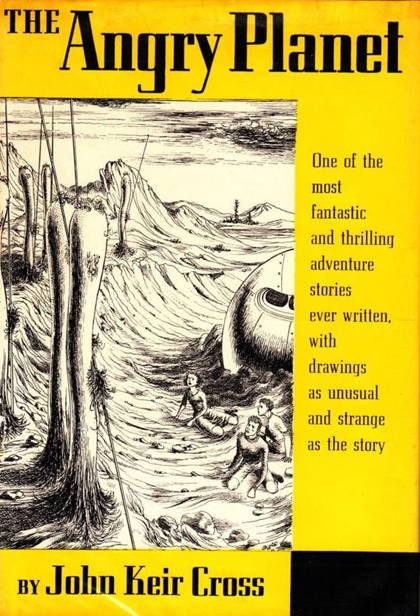

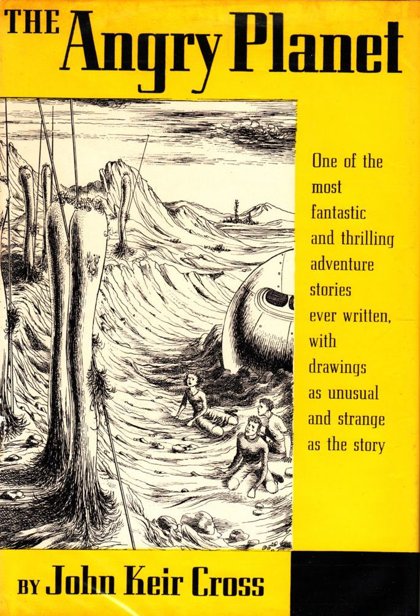

The Angry Planet

Authors: John Keir Cross

THE ANGRY

PLANET

AN

AUTHENTIC FIRST-HAND ACCOUNT

OF A

JOURNEY TO MARS IN THE SPACE-SHIP

Albatross,

COMPILED

FROM NOTES AND RECORDS BY

VARIOUS

MEMBERS OF THE EXPEDITION,

AND

NOW ASSEMBLED AND EDITED FOR

PUBLICATION

BY

FROM MANUSCRIPTS MADE AVAILABLE BY

THE ILLUSTRATIONS ARE BY

COWARD-MCCANN

INC

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT,

1945, BY

PETER LUNN (PUBLISHERS) LIMITED,

LONDON

COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY COWARD-MCCANN,

INC.

Tenth

Impression

Typography by Robert Josephy

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA

a collaborative eBook

Typography converted to

Palatino Linotype

TO AUDREY

CHAPTER I. AN INTRODUCTION

by Stephen MacFarlane

CHAPTER II. A HOLIDAY IN SCOTLAND,

by Paul Adam

CHAPTER III. ON ROCKETS AND SPACE-SHIPS

by Andrew McGillivray

CHAPTER IV. A JOURNEY THROUGH SPACE,

by Various Hands

CHAPTER V. A MARTIAN LANDSCAPE

by Jacqueline Adam

CHAPTER VI. THE MEN OF MARS

by Stephen Macfarlane

CHAPTER VII. FIRST SIGNS OF AN ENEMY,

by Paul Adam

CHAPTER VIII. THE FIGHT FOR THE “

ALBATROSS

,”

by

Stephen Macfarlane

CHAPTER IX. ALARUMS AND EXCURSIONS

Part 1. A THEORY OF MARTIAN LIFE

by Stephen MacFarlane

Part 2. A THEORY OF MARTIAN LIFE

by Andrew McGillivray,

F.R.S., Ph.D.

CHAPTER X. CAPTURED!

by Michael Malone

CHAPTER XI. ATTACK,

by Stephen Macfarlane

CHAPTER XII. THE RETURN TO EARTH,

by Various Hands

AN EPILOGUE,

by John Keir Cross

Illustrations

IMPORTANT

Editor’s Note on the Illustrations

Originally we had meant to

illustrate this book with real photographs—Dr. McGillivray took several good

cameras to Mars with him. He, Mr. MacFarlane, and the children, all used a lot

of film in snapping the Martians, their houses, cities, landscapes, and so on.

But there must have been something in the chemical composition of the rarefied

air on Mars that was deleterious to the emulsion on the negatives, for when the

photographs were developed on earth after the journey, we found that they were

either completely blank or so misty that any reproduction of them was out of

the question. However, Mr. Robin Jacques, the artist who has done all the

drawings in this book, worked most carefully from descriptions supplied by the

Albatross

travelers. And they

all agree that his pictures are true representations of what they saw during

their fantastic adventures in the strange, romantic and terrible places they

visited so many millions of miles away.

J.K.C

.

Living creatures—individuals—Martians!

A floating game near the

ceiling

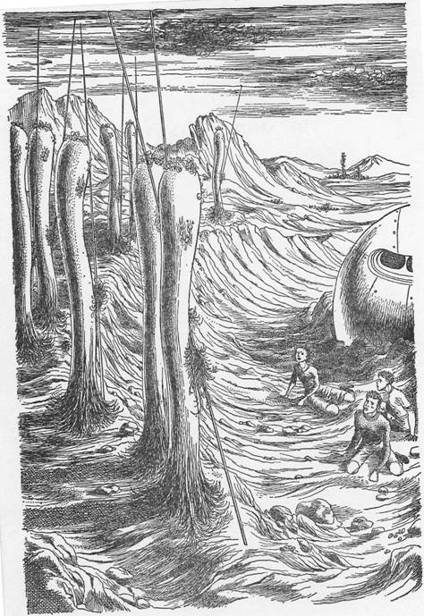

What we saw was awe-inspiring

and strange

Mike was swung up into the

air, kicking and shouting furiously

I was free—absolutely alone

under the blue sky

A huge white shape—a

monstrous swaying toadstool

Enormous tremors shook

the earth

We landed the

Albatross

in Northern France

AN INTRODUCTION by Stephen MacFarlane

MOST of the civilized world knows by this time the

main outline of the story of the remarkable flight to the planet Mars made by

Dr. McGillivray, of Aberdeen, Scotland, in his space-ship

Albatross

.

This book, however, is the first publication to put forth any sort of

description of the extraordinary adventures that befell Dr. McGillivray’s party

on what has been called “the Angry Planet.” Naturally, Dr. McGillivray has

published various articles in the scientific journals (he is now engaged on the

compilation of a full-length book that will describe in detail his innumerable

valuable findings). But he—being a scientist (and I know he will not mind my

saying this)—is inclined in his works to pay little attention to what may be

called the human side of things. So we have put together this book. It

ignores—or at any rate only covers sketchily—the scientific aspect of the

adventure, and concerns itself almost entirely with what happened before and

during the flight, and on Mars itself.

Students of the Press will remember the world-wide

sensation caused by the news, after Dr. McGillivray’s return to earth, that

there had been three stowaways on the

Albatross

during its visit to

Mars—two boys and a girl. The Doctor’s daring achievement in bridging some 35

million miles of space was spectacular enough, heaven knows: but to think that

three young people—schoolchildren—had gone through the unique experience with

him, and he had not even known of their presence in the

Albatross

till

the space-ship was well away from the earth—that was news indeed! The children

were fêted, filmed, interviewed, asked to speak on the radio, and presented to

every Lord Mayor in the country (or so it seemed to them). By this time the

shouting and the tumult have died a little, which is a good thing, for the

children were heartily sick of all the fuss and were glad to get back to

normal. Not that things in their own minds ever got out of perspective—they

were, all three of them, too sensible to get swollen heads over the affair. But

after their fantastic adventures on Mars they needed a rest in which to collect

their thoughts. They have now had that rest—and, in one sense, this book proves

that they have collected their thoughts; for, as you will see, they—the

children—have helped to write it.

Perhaps I should, at this point, introduce myself. My

name is Stephen MacFarlane, and I am (as perhaps some of you may know) a

writer. I am also the uncle of one of the adventurous children—the youngest

one, Mike Malone. The other two were (and, of course, still are) his cousins,

Paul and Jacqueline Adam. Being Mike’s cousins they are, in a sense, also

related to me, although so distantly that we have never bothered to work it all

out properly. They call me Uncle Steve, of course, but I like to think that this

is mainly because uncle is a term of affection!

When Dr. McGillivray—my very good friend—began

experimenting some years ago with rockets and spaceships, I was his only

confidant. He is, as is well known, a reticent man, wrapped up in his

scientific studies. His Doctor’s degree comes from his having graduated in

Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews. He is still quite a young man—in

his early forties. But, as I have said, he was shy to a degree of disclosing

any of his thoughts to outsiders—I was his only real friend. The history of our

friendship is an interesting one, which, alas, I have no time to tell here. It

will be sufficient to say that I valued his confidence deeply. When he told me

that he was experimenting with rockets, that he believed strongly that he would

someday design one capable of carrying passengers on stratosphere flights—that

he even visualized rocket flights to the moon and the planets as a possibility,

I was enormously excited. It was a subject I was intensely interested in myself.

I had always believed in the possibility of life on other planets—life

different from life as we knew it, perhaps, but still life. So I encouraged the

Doctor with my enthusiasm, and even made over most of my savings to him so that

he could go on with his experiments.

That was our chief trouble—money. The cost of the

experiments was prodigious. It was a matter, you see—putting it briefly—of

finding a fuel. The designing of an interplanetary rocket ship was,

comparatively speaking, easy enough—though, as you can imagine, there were

countless factors to be considered: weight, resistance to pressure and

friction, how to produce oxygen for breathing, and so on. But all these things

were easy of solution compared with the immense problem of finding a fuel—a fuel

powerful enough to carry us right through the stratosphere and to give us

enough impetus to take us to the gravity belt of the particular planet we

proposed visiting: yet a fuel light enough and compact enough to allow of us

storing sufficient of it in the rocket to be able to make a return flight to

earth.