The Anybodies (14 page)

Authors: N. E. Bode

THE LIMP

STAY FOCUSED NOW! STAY SHARP! THAT'S MY

advice, because things may pick up speed and get a little jostled like those roller coaster boxcars on their tight, loopy tracks, and I don't want you to topple out, or something dreadful like that. I'm doing the best I can, and I can't think of any advice from my old writing instructor that would help me now. He never wrote a book with so much going on. In fact, his books are dry and dusty, big fatty books that sit on library shelves until you check them out just to let them get some air, because you feel sorry for them. I hope the rest of this goes well. I can hear that roller coaster motor chugging and whining and, actually, I don't like roller coasters. Once I got

off one and threw up on my shoes.

The Miser has had some time to think. Once he turned himself back into the Miser and especially while he was waiting for Mrs. Appleplum to shuffle in and untie him, he was thinking. He was shaking the blurred vision of love from his head and he was putting things together. He knew Fern had Eliza's diary and that Fern was jiggling things from it. That's how the Miser ended up under the peach tree. And if Eliza had written about

The Art of Being Anybody

âhow couldn't she have?âFern could possibly even shake the book from the diary. So he was nearly convinced that Fern already had

The Art of Being Anybody

, or almost. By the time he was untied and striding out of his room, he had one more question: what was more important to Fern than the book? What?

Â

The old jalopy was acting up, even more than usual. When the Bone and Fern drove in the long driveway and parked, the Bone got out of the car and lifted its rusted hood to look at the engine. Fern went inside the house to tell Mrs. Appleplum that they were expecting a very important phone call, and that they'd want to answer the phone from now on, if that was okay with her.

“Mrs. Appleplum?” Fern called. “Mrs. Appleplum?”

There was no answer. So Fern called out again, but this time she called for Mr. Haiserblaitherness. You see, ever since Fern was in the Miser's room, she was dying to

know what he was writing. The letters in those envelopes hadn't gone very far from her mind. Was it part of a dastardly plot of his? The house seemed empty. Maybe this was her chance. She walked up the stairs, calling again and again for Mr. Haiserblaitherness. Still no answer. She called once more, in front of his door, then turned the knob. It opened easily. (She'd taken the key the night before, and he'd had no way of locking it on his way out.)

Fern couldn't help but think there was something alive in the room. The window was open wide now, and the envelopes under the bed were still rustling. Fern moved to the desk. There were envelopes with Mrs. Appleplum's address on them and other letters sitting out. Fern started reading.

Dear Mrs. Appleplum,

I'm sorry I didn't attend breakfast. And apologize for any rudeness last night. I am not myself.

Sincerely,

M.

The next letter read:

Dear Mother,

The wind is warm here. And I miss you terribly. Tell sister

Imogene that I think of her. I often wonder if she married the grocer. I hope Father's back has held up from all of his strongman lifting and that he's stopped eating those nails. It isn't good for his digestion. It's been so many years since I've been in touch. As you know, I haven't been myself.

Love,

M.

There were letters to Imogene, to the grocer, to the Miser's old landlord, an apology for lyingâhe had, in fact, sealed some small holes in the walls with toothpaste and had left milk in the refrigerator to sour. Fern started opening envelopes under the bed. There were letters to his old piano teacher thanking her for her kindness and apologizing for his lack of diligent practicing, and long weepy epics to his nanny. There were letters to the Bone. They were warm and honest and filled with regret. Fern was shocked. All of the letters ended the same way:

As you know, I haven't been myself.

Who was the Miser?

Just then there was a rustle of wings, a quick flap-flapping. A crow appeared on the windowsill. It was a giant black crow. It cawed loudly. Fern knew she was being scolded. Was it the Miser, transformed? She quickly put the letters back in their envelopes and under the bed.

“Sorry,” Fern said.

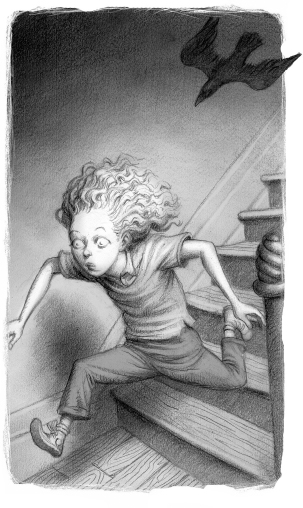

The crow looked at her sadly. It cawed again, a high cry. Fern thought the crow might hop to her and sit in her lap. It seemed so forlorn. But, no, the crow puffed up its chest. It began beating the air. It rushed at Fern, and she screamed. She ran out the bedroom door, and the crow was after her. She turned and ran down the stairs, past her black umbrella in the parlor, through the kitchen and out the back door to the yard. She felt the crow flap violently around her, up, up into the sky.

Fern stood there, breathing hard, with her hands on her hips. Had the Miser, in the shape of a crow, just caught her with his secret? Or had it been a crow? Sometimes a crow is just a crow.

Out in the distance, she saw a shape stand up in the garden. It looked like Mrs. Appleplum, her dress, her swoop of hair; but she was standing upright, not hunched even the least little bit. In fact, she seemed rather tall. She was striding confidently around the garden with a set of clippers. She stopped suddenly as if she felt Fern watching her. She looked up, then rummaged through her pocket. She held up a letter over her head. Fern walked toward her, and she walked toward Fern. They met in the middle of the yard. There was nothing arthritic about Mrs. Appleplum now. Nothing at all, except for a small limp, just a little limp in one leg. It reminded Fern of the bird that turned into a dog. Fern's

heart was pounding in her chest.

“This is for you,” her grandmother said. She handed the letter to Fern, and Fern recognized the handwritingâthe Miser's.

Fern took the letter, but her head was spinning. Shaken by the angry crow in the Miser's room and by having just been at her old house, which was not her homeâit had never really been her homeâFern wanted to confess to Mrs. Appleplum, more than ever before, that she was not Ida Bibb, but her granddaughter. She remembered the kiss Mrs. Appleplum had given her on her cheek and how she had wanted to hug her after dealing with all of the creatures in the yard. Fern remembered how it had felt to have her hand in the goldfish pond that first time. She said, “Iâ¦Iâ¦haven't been honest.”

“It's okay,” the old woman said. “I haven't been honest either.”

“Your name is Dorathea Gretel. I know, but⦔

“Yes, and you know I have a limp from an accident. You know about the accident too, don't you? You saw me once get hit by a car, but you didn't know it was me. I thought you might put it together though. So I took on many limps so that you wouldn't recognize that limp. You're very smart,

Fern

.”

Fern looked at her. Her eyes welled up. Her heart swelled. Her grandmother knew who she was, had always known. Had she known her since she was just

a baby? “When I was a little,” Fern said, “there was a book, and I shook crickets out of it, a whole roomful!” It felt wonderful to be able to tell her anything she wanted, anything at all.

Mrs. Appleplum smiled and shook her head. “Things aren't always what they seem, are they?”

Fern remembered the snowflakes that had turned into scraps of paper and the little sentenceâ

that

little sentence, that she had lined up on her desk. “No,” she said. “They aren't.”

Mrs. Appleplum pulled Fern to her chest. She hugged her tightly. She smelled of sweet lemons and the garden's dirt. And Fern knew that Mrs. Appleplum had been keeping an eye on her for a long time. She'd been the bird on her windowsill, and the bat that had turned into the marble. She'd been the tree and the nun and the lamppost, and she'd known everything all along.

“Do you want your umbrella back?” Fern asked.

“That old thing? No, thank you. I'm not sure why you held on to it. It's dented, you know.”

This made Fern laugh and cry at the same time. Has that ever happened to you? It's such a strange and wonderful thing. If it hasn't ever happened to you, I hope it does one day.

“Hush, my girl, hush. We've got work to do,” Fern's grandmother said. “The Bone is gone.”

SWEET, SWEET

THE KIDNAPPING

(actually, The Adultnapping, right?)

FERN TORE TO THE FRONT YARD, WHERE SHE

found the Bone's old jalopy, its hood still cranked open. Her grandmother called her to the house. Fern ran to her, ripped open the letter her grandmother had been holding and read it out loud while following her grandmother upstairs.

Dear Fern,

I have the Bone. I want the book. I believe you've heard of

The Art of Being Anybody

? I'll come to collect it at three o'clock. Don't try to find us. We'll find you. If I don't have it

today, I'll have to do something terrible to the Bone. I don't want to do this terrible thing. But as you know, I haven't been myself.

Sincerely,

M.

Fern began, “Do you knowâ”

“The Miser, yes. He was a fine enough boy. His name was Michael, once upon a time. Your mother cared for him, but didn't love him.”

“Did you knowâ”

“I knew Mr. Haiserblaitherness was the Miser, certainly. Just as I knew you and your father were never the Bibbs.”

“And Mr. and Mrs. Drudger⦔

“They are nice people, Fern. They took care of you well. A bit dull, but nice.”

“How comeâ”

“You could get crickets to pop out of a book as a little, little girl, but now you have to relearn it? Well, children can do so many things until they're told they can't. This is true of you, as an Anybody, but it's true for other children, too.”

“You've been⦔

Here Fern's grandmother turned. They now stood near the entranceway to her grandmother's bedroom.

It was the only room in the house Fern hadn't seen yet. “Yes, I've been the one keeping an eye on you. I knew that you would come to me, when you needed me. In your own time. This is the way it was meant to work, Fern.”

“Do you knowâ”

“Of course I know where

The Art of Being Anybody

is. Do you think I'd leave it laying about?”

Her grandmother twisted the knob and opened the door. Inside was a jungle of books, and everything in it, truly everything, was made of booksâthe night stand, the dresser, even the bookcase that held books was made of books. The bed had a coverlet, dust ruffle, and canopy of soft, old canvaslike parchment with ancient scrawl. The curtains were made of the same material. The lamp shade was an octagon of thin books wired together. Fern turned and turned in the room, the ceiling, the wallsâall books. The floor, too, was completely covered by leather bindings, like a brick path. She bent down and opened the book at her feet:

Admiral Hornblower

in the West Indies. She went to pick it up off the floor.

“I wouldn't do that, if I were you. Those books aren't lying on the floor. They

are

the floor. If you lie on your belly, though, you can still read it.”

“Maybe later,” Fern said.

Her grandmother smiled. “When I give you

The Art of Being Anybody

, Fern,” she said, “you can do anything

with it. I mean anything. You can use it in such a way that, eventually, one day, you could be a world leader. In fact, if you learn everything it has to offer, you could rule the world. Do you understand?”

“I don't want to rule the world. I want the Bone back.”

Her grandmother shook her head. “I've heard this before, you know. It's what your mother said when the Bone was coming for her. We were standing in this very room. And do you know what I said?”

“No,” Fern said.

“I told her that she could take the book, but that she was making a mistake by going off with the Bone. A terrible mistake.”

“But, butâ”

“I know now,” Fern's grandmother said. “I know now that she was right. The Bone found the ladder behind the barn, and when he got to the top of it, Eliza was thereâher face flushed and bright. She chose love or it chose her. Love, Fern. And when she called me from the hospital, she told me that lying beside her was the book. She told me that I should come and get it, later, after. âAfter what?' I asked. But she didn't answer. I went to the hospital. And she was gone. I told this anxious, sputtering nurse that I wanted to look at the babies. She took me to a window, and I looked out over the sea of faces. I found you, and I knew you were one

of ours. âThere,' the nurse said. âThere he is. Baby Boy Bone.' And she was pointing to a squinty baby in a blue blanket. I knew she was wrong, but I didn't say a word. Fate. I knew it was fate. I shouldn't interfere, that you would come to me, one day. I cried and cried. I said, âI'll see you again, Baby Girl Drudger.' And I took the book.”

Fern was crying now, tears streaming down her face. Her grandmother lifted her chin with her hand. “Do you know why the Bone is called the Bone?”

Fern shook her head. She'd asked once but the question had ruffled the Bone, and so she never pursued it.

“Eliza told me his mother named him that when he was a baby because he was so sweet that it seemed he had an extra bone in his body, a sweet bone.”

“He thinks he's tough,” Fern said, smiling.

Mrs. Appleplum smiled. “Let's go save him.” She opened a drawer on her bedside tableâthe one spot where you'd expect someone to put a book, the most obvious spotâand she pulled out a big leather-bound book with a thin leather belt around it, just as the Bone had described. It had gold lettering on its front cover:

THE ART OF BEING ANYBODY

; under it, in smaller gold letters:

OGLETHORP HENCEFORTHTOWITH

.

“Here,” said Mrs. Appleplum, “open it.” She handed Fern the book, and Fern took its heavy weight into her arms. She closed her eyes, held the book to her chest and

thought of how her mother once had held this exact same book the exact same way. She ran her hand over the gold letters and along the thin leather belt. “Go on,” Mrs. Appleplum urged.

Fern unhooked the belt and opened the book, but just as the Bone had warned her, it made no sense. It was in an awful, jumbled mess. Unlike Fern's mother's diary, there would be an occasional word, a terrible, senseless word like “notwithstanding” or “aforementioned,” but that was it. “I can't read it,” Fern admitted.

Mrs. Appleplum took the book back. First she pulled a purple crayon from her pocket. “No, no, not this one,” she said. Next she found a black ink pen. “Of course you can't read this book. You can't read it any more than I can. This book doesn't belong to you!” Her grandmother showed her the first page of the book, where there was a sign you see in many books. It read,

THIS BOOK BELONGS TO

: and there was a list of names. The last on the list was Eliza, just thatâEliza. Fern's grandmother said, “Do you know why your mother was such a good Anybody?”

Fern shook her head.

“She knew who she was, deep down. To become someone else or something else you have to know yourself first.” She handed her the pen. “Write your name,” she said.

Fern thought a moment. Who was she? She wasn't

Fern Drudger. She wasn't ever really. She wasn't Ida Bibb. She hadn't ever been called Fern Bone and she hadn't ever been called Fern Gretel, her grandmother's last name. She could say that she was the Bone's daughter or she could say she was Mrs. Appleplum's granddaughter. But none of those things seemed to fit. And so she simply wrote

FERN

, in small letters, and that seemed right.

“Now close the book and open it again.”

Fern did just that, and when she opened it to a page in the middle of the book, every word was clear. In fact, the page she turned to was Chapter Six: Hypnotizing and Dehypnotizing Objects. Fern thought of her mother's diary. Maybe it wasn't in code after all, but hypnotized! “When trying to dehypnotize said book, it is best and most appropriate to concentrate, ruminate and cogitate on the binding first, just as it's best to concentrate on a beak when transforming into a birdâ¦.”

“Now the book is yours,” her grandmother said. “Oglethorp Henceforthtowith had the ability to hypnotize objects, such as books, as well as people. So he wrote this book and then hypnotized it so that it could only be read by its owner. Wasn't he a very smart writer?” The Henceforthtowiths have a long and sordid historyâsome wondrous and some dastardly. I won't go into it in this book. It would be too overwhelming, for you and for me. But the answer to this question was yes,

Oglethorp Henceforthtowith was a very, very smart writer. Very smart. Very smart indeed.

Fern closed the book, rehooking its belt. She had one more question, though. There was one thing she thought she needed to put into action before going to save the Bone. She wasn't sure why she felt she had to do it, but she was sure it was important, urgent. She said, “I think it's better to tell people how you feel and not keep it bottled up, don't you?”

“Yes, I do,” her grandmother said.

“Well, then, there's some mail that needs to be delivered. And I think I'll need an army to do it.”