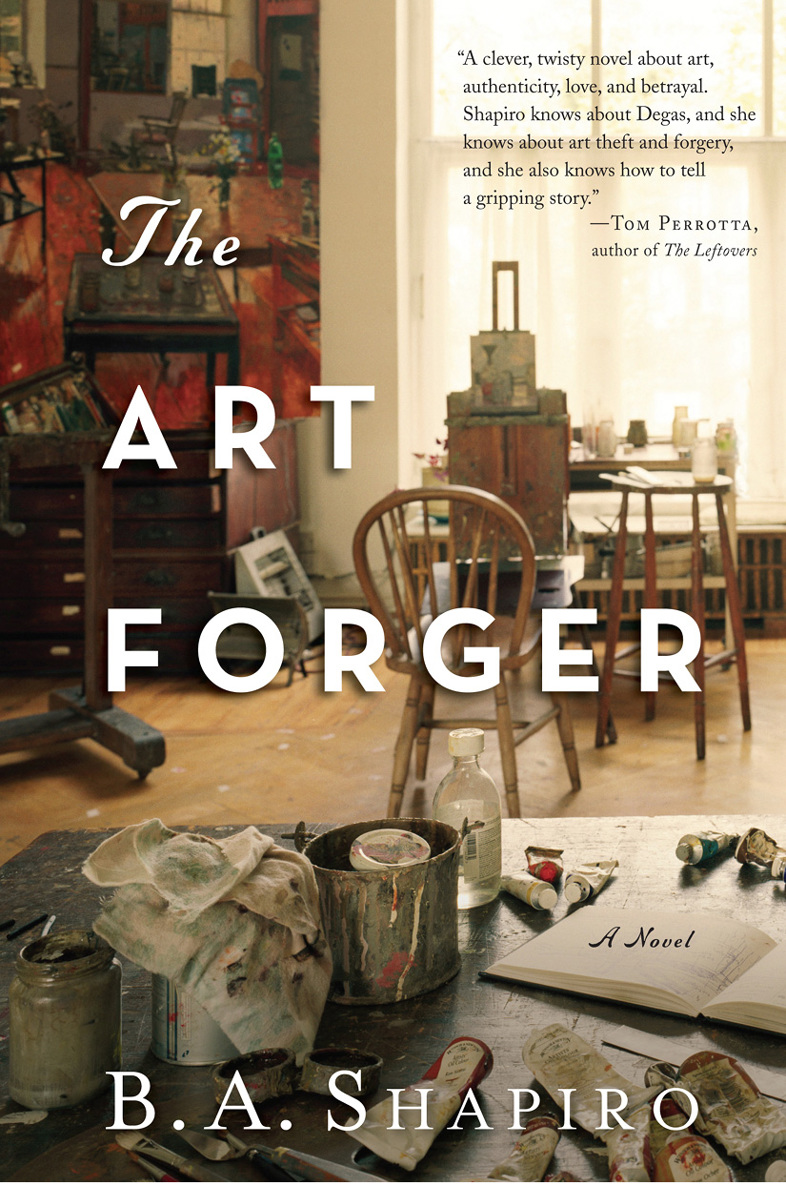

The Art Forger

The

ART FORGER

A NOVEL BY

B. A. SHAPIRO

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

2012

To Dan, who never gave up

A painting is above all a product of the artist’s imagination; it must never be a copy.

—EDGAR

DEGAS

GARDNER HEIST 21st ANNIVERSARY

Largest Art Theft in History Remains Unsolved

Boston, MA

—

In the early morning hours of March 18, 1990, two men dressed as police officers bound and gagged two guards at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and stole thirteen works of art worth today over $500 million.

The cache included priceless masterpieces such as Rembrandt’s “Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” Vermeer’s “The Concert” and Degas’ “After the Bath.” Despite thousands of hours of police work, a lapsed statute of limitations and a $5 million reward, the artwork has not been recovered.

Over the last two decades, the FBI investigated known art thieves and suspects connected to organized crime, international terrorism and the Catholic Church. Agents followed leads across the United States, Europe and Asia. Suspects included the son of a police officer, the Irish Republican Army, Whitey Bulger and the Boston mob, an antiques dealer, a Scotland Yard informant and a New York City auction house employee. No arrests have been made.

The Gardner Museum asks that anyone who has any information on the whereabouts of the lost artworks contact the Boston office of the FBI.

Boston Globe

March 17, 2011

One

I step back and scrutinize the paintings. There are eleven, although I have hundreds, maybe thousands. My plan is to show him only pieces from my window series. Or not. I pull my cell from my pocket, check the time. I can still change my mind. I remove

Tower,

a highly realistic painting of reflections off the glass Hancock building, and replace it with

Sidewalk,

an abstraction of Commonwealth Avenue through a parlor-level bay window. Then I switch them back.

I’ve been working on the window series for over two years, rummaging around the city with my sketchbook and Nikon. Church windows, reflective windows, Boston’s ubiquitous bays. Large, small, old, broken, wood- and metal-framed. Windows from the outside in and the inside out. I especially like windows on late winter afternoons before anyone inside notices the darkening sky and snaps the blinds shut.

I hang

Sidewalk

next to

Tower.

Now there are a dozen, a nice round number. But is it right? Too many and he’ll be overwhelmed. Too few and he’ll miss my breadth, both in content and style. It’s so difficult to choose. One of the many reasons studio visits make me so nervous.

And what’s up with this visit anyway? I’m a pariah in the art world, dubbed “the Great Pretender.” Have been for almost three years. And suddenly Aiden Markel, the owner of the world-renowned Markel G, is on his way to my loft. Aiden Markel, who just a few months ago barely acknowledged my presence when I stopped by the gallery to see a new installation. And now he’s suddenly all friendly, complimentary, asking to see my latest work, leaving his tony Newbury Street gallery to slum it in SOWA in order to appreciate my paintings, as he said, “in situ.”

I glance across the room at the two paintings sitting on easels.

Woman Leaving Her Bath,

a nude climbing out of a tub and attended to by a clothed maid, was painted by Edgar Degas in the late nineteenth century; this version was painted by Claire Roth in the early twenty-first. The other painting is only half-finished: Camille Pissarro’s

The Vegetable Garden with Trees in Blossom, Spring, Pontoise

à la Roth. Reproductions.com pays me to paint them, then sells the paintings online as “perfect replicas” whose “provenance only an art historian could discern” for ten times my price. These are my latest work.

I turn back to my windows, pace, narrow my eyes, pace some more. They’ll just have to do. I throw a worn Mexican blanket over the rumpled mattress in the corner then gather the dirty dishes scattered around the studio and dump them in the sink. I consider washing them, decide not to. If Aiden Markel wants in situ, I’ll give him in situ. But I do fill a bowl with cashews and pull out a bottle of white wine—never red at a studio visit—and a couple of glasses.

I wander to the front of the studio and look out the row of windows onto Harrison Avenue. The same view as

Loft.

I spend a lot of time in this spot, pretending to work through my latest project, but mostly daydreaming, spying, procrastinating. It’s four stories up, and each of the six windows in front of me stretches from two feet above the floor to two feet below the fifteen-foot ceiling.

This building was once a factory—handkerchiefs, some old-timer told me. But the old-timers aren’t known for their veracity, so it could have been hats or suspenders or maybe not even a factory at all. Now it’s a warren of artists’ studios, some, as in my case, live-in studios. Illegal, of course, but cheap.

According to media hype, SOWA—South of Washington—is the new trendy district in the south end of Boston’s South End; the north was the new trendy area about ten years ago. But to me, and to anyone who spends any time here, it’s barely on the cusp. Warehouses, projects, a famous homeless shelter, and abandoned basketball courts form the base of a neighborhood erratically pockmarked with expensive restaurants, art galleries, and pristine residential buildings protected by security. The roar of I-93 is so constant it sounds like silence. I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.

Below, Aiden Markel turns the corner from East Berkeley with his lanky, graceful stride. Even from half a block away, I can see he’s wearing perfectly tailored pants—most likely linen—and what’s probably a $500 shirt. It’s eighty-five degrees on a late summer afternoon, and the guy looks as if he stepped out of his Back Bay condo on a cool September morning. He pulls out his cell, glances at my building, and touches the screen. My phone rings.

T

HERE’S NO ELEVATOR

and no air-conditioning in the hallways and stairwells. As we hit the fourth floor, Markel’s breathing is steady and his clothes are bandbox. Clearly, the man spends time in the gym. Not to mention that he hasn’t stopped talking since I let him in the door. No one would guess we’ve barely spoken to each other in three years.

“I was around the corner from here just the other day,” Markel says, continuing his running monologue of small talk. “Dedham and Harrison. Looked at Pat Hirsi’s newest project. You know him, right?”

I shake my head no.

“He’s working with cobblestones. Very ingenious.”

I pull open the wide steel door with two hands.

Markel steps over the threshold, takes a deep breath, and closes his eyes. “Nothing like the smell of an artist at work.” He keeps his eyes closed, which isn’t exactly what I want him to do; he’s supposed to be here to look at my paintings, fall in love with them, and set me up with a one-woman show at Markel G. Right. Like that’s going to happen. Although, what is going to happen or why he’s here is beyond me.

“How about a glass of wine?” I ask.

He finally opens his eyes and gives me a slow, warm smile. “Will you be joining me?”

I can’t help but smile back. He’s not classically handsome, his features are too large for that, but there’s something in the way he carries himself, the wide deep-set eyes, the dimple in his chin, that tugs at me. Charisma, I guess. That and our shared history.

“Sure.” I grab a pile of canvases I somehow forgot were on my beaten up couch and lean them against an even more beaten up coffee table. Sometimes I think I’m a living parody of myself: the starving artist sleeping on a mattress in her studio to save on rent. Yet, there it is.

Markel doesn’t move. He stares at me for a long moment then shifts his gaze over my shoulder, a wistful look on his face. I know he’s thinking about Isaac. I probably should just say something, but I don’t know what to say. That I’m sorry? That I’m still upset? That I lost a friend, too?

I pour wine into two juice glasses as he settles into the couch. Not an easy feat as it’s lumpy and too deep for comfort. I should get a new one, or at least a new secondhand one, but the landlord just raised my rent, and I’m pretty much broke.

I sit in the rocking chair across from him and lean forward. “I heard your Jocelyn Gamp show went fabulously well.”

He takes a sip of his wine. “It was her molten pieces. She sold everything she had. Plus three commissions. Amazing lady. Amazing artist. The Met’s requested a studio visit.”

I like how he doesn’t take any of the credit. “She sold” rather than “I sold” or even “we sold.” Extremely rare among the run-amok egos of most dealers and gallery owners.

“Not often a Boston show gets covered in the

New York Times,

” I suck up.

“Yes, it was quite the coup,” he admits. “I’m glad to see that you’re still following the goings-on in the art world even though we haven’t exactly been following yours.”

I look up sharply. What the hell does that mean? But I see that his eyes hold compassion, maybe even a little guilt.

“Isaac’s

Orange Nude

sold last week,” he says.

Ah. As everyone knows, I was the model for

Orange Nude.

Even though it’s an abstraction, there’s no denying my long, unmanageable red hair or the paleness of my skin or my brown eyes. If I hadn’t thrown it out the door when we broke up, I’d probably be living in a condo in Back Bay instead of renting in an industrial building in SOWA. But then again, I’m not the Back Bay type. “Don’t tell me how much you got for it.”

“I’ll spare you the pain. But the sale started me thinking about you, about the raw deal you got.”

I struggle to keep the surprise off my face. In the last three years, no one outside of a few art buddies and my mother—who never really understood what it all meant—has looked at the situation from my point of view.

“So I decided to come down and see what you’ve been up to,” he continues. “Maybe I can help.”

My heart leaps at the offer, and I jump up. “I pulled out a few from my latest series.” I wave at the paintings. “Obviously, windows.”

Markel walks toward the pieces. “Windows,” he repeats, and he takes in the whole dozen from a distance, then approaches each individually.

“It’s urban windows, Boston windows. Hopper-esque thematically, but more multidimensional. Not just the public face of loneliness, but who we are in many dimensions. Unseen from the inside. Or unknowingly seen. On display from outside, posturing or forgetting. Separations. Reflections, refractions.”

“Light,” he murmurs. “Wonderful light.”

“That, too. Without light nothing can be seen. And with it, still so much is unobserved.” Studio visits make me talk like a pompous art critic.

“Your light is amazing. The subtle values. Almost Vermeer-like.” He points to

Loft.

“I’m struck by the difference in value in the light from the far left window through to the right ones.” He steps closer. “Each slightly different, and yet each such a luminous part of the whole.”

I’m also pleased with that particular play, but Vermeer, the master of light . . .

“How many glazings are you doing?”

I’m reluctant to admit the truth. Not only are very few artists using classical oil techniques these days, but those who are aren’t nearly as compulsive as I am about layering. I shrug. “Eight? Nine?” Which is actually low for me.