The Articulate Mammal (33 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

DOG INTO INTO OF

It was also unlikely that they would accept:

GOLDFISH MAY EAT CATS.

or:

SKYLARKS KISS SNAILS BADLY.

But there was nothing really wrong with these grammatically: these were accidental facts about the diet of goldfish and the amatory preferences of skylarks which need not be included in the grammar.

So Noam went away again and thought hard. It dawned on him that all sentences were straightforward word ‘strings’: they were composed of words strung together, one after the other. And the order in which they occurred was partially predictable. For example, THE had to be followed either by an adjective such as GOOD, LITTLE or by a noun such as FLOWER, CHEESE, or occasionally an adverb such as CAREFULLY as in:

THE CAREFULLY NURTURED CHILD SCRIBBLED OBSCENE GRAFFITI ON THE WALLS.

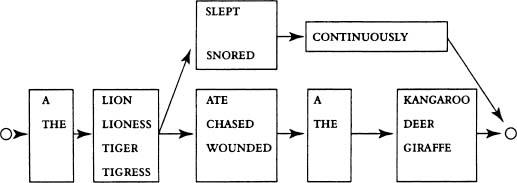

Perhaps, he pondered, one’s head contained a network of associations such that each word was in some way attached to the words which could follow it in a sentence. He started to devise a grammar which started with one word, which triggered off a choice between several others, which in turn moved to another choice, until the sentence was complete:

This simple device could account for quite a number of different sentences:

A LION ATE A KANGAROO.

THE TIGRESS CHASED THE GIRAFFE.

and so on. If he continued to elaborate it, perhaps it could eventually include all possible sentences of English.

He presented it to the Emperor, who in turn showed it to the other Englishmen. They pointed out a fatal flaw. Such a device could not possibly account for a speaker’s internalized rules for English, because English (and all other languages) has sentences in which nonadjacent words are dependent on one another. For example, you can have a sentence:

THE LIONESS HURT HERSELF.

If each word triggered off the next only, then you would not be able to link the word following HURT with LIONESS, you would be just as likely to have

THE LIONESS HURT HIMSELF.

Similarly, a sentence starting with EITHER, as in

EITHER BILL STOPS SINGING OR YOU FIND ME EAR-PLUGS.

would not fit into this system, since there would be no means of triggering the OR. Furthermore, in this left-to-right model, all the words had equal status, and were linked to one another like beads on a necklace. But in language, speakers treat ‘chunks’ of words as belonging together:

THE LITTLE RED HEN/WALKED SLOWLY/ALONG THE PATH/SCRATCHING FOR WORMS.

Any grammar which claimed to mirror a speaker’s internalized rules must recognize this fact.

Noam, therefore, realized that an adequate grammar must fulfil at the very least two requirements. First, it must account for

all

and

only

the sentences of English. In linguistic terminology, it must be

observationally adequate

. Second, it must do so in a way which coincides with the intuitions of a native speaker. Such a grammar is spoken of as being

descriptively adequate

.

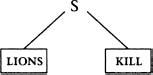

Noam decided, as a third attempt, to concentrate on a system which would capture the fact that sentences are split up into chunks of words which go

together. He decided that a multi-layered, ‘downward branching’ system was the answer. At the top of the page he wrote the letter S to represent ‘sentence’. Then he drew two branches forking from it, representing the shortest possible English sentence (not counting commands).

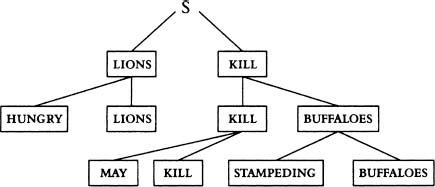

Then each branch was expanded into a longer phrase which could optionally replace it:

This tree diagram clearly captured the

hierarchical

structure of language, the fact that whole phrases can be the structural equivalent of one word. It diagrammed the fact that HUNGRY LIONS functions as a single unit in a way that KILL STAMPEDING does not.

The Emperor of Jupiter was delighted. For the first time he began to have an inkling of the way language worked. ‘I want some soup … some seaweed soup … some hot seaweed soup … some steaming hot seaweed soup,’ he murmured to himself, realizing the importance of Noam’s new system.

The other Englishmen praised the system, but grudgingly. They admitted that the tree diagram worked well for sentences such as:

HUNGRY LIONS MAY KILL STAMPEDING BUFFALOES.

But they had one major objection. Did Noam realize just how many trees might be required for the whole language? And did he realize that sentences which speakers felt to be closely related would have quite different trees? For example:

HUNGRY LIONS MAY KILL STAMPEDING BUFFALOES.

would have a tree quite different from:

STAMPEDING BUFFALOES MAY BE KILLED BY HUNGRY LIONS.

And a sentence such as:

TO CHOP DOWN LAMP POSTS IS A DREADFUL CRIME.

would have a different tree from:

IT IS A DREADFUL CRIME TO CHOP DOWN LAMP POSTS.

Worse still, had Noam noticed that sentences which were felt to be quite different by the speakers of the language had the same trees?

THE BOY WAS LOATH TO WASH.

had exactly the same tree as:

THE BOY WAS DIFFICULT TO WASH.

Surely Noam could devise a system in which sentences felt by speakers to be similar could be linked up, and dissimilar ones separated?

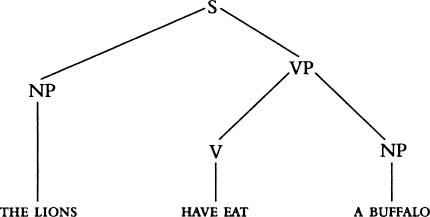

After much contemplation, Noam realized he could economize on the number of trees needed, and he could also capture the intuitions of speakers that certain sentences were similar if he regarded similar sentences as belonging to the same basic tree! Actives and passives for example, could be related to an underlying tree:

Then this ‘deep structure’ tree could be ‘transformed’ by operations known as transformations into different surface structures. It provided the basis for both ‘the lions have eaten a buffalo’ and ‘a buffalo has been eaten by the lions’.

Using the same principle, Noam realized that he could explain the similarity of

TO CHOP DOWN LAMP POSTS IS A DREADFUL CRIME

IT IS A DREADFUL CRIME TO CHOP DOWN LAMP POSTS.

Conversely, the difference between

THE BOY WAS LOATH TO WASH.

THE BOY WAS DIFFICULT TO WASH.

could be explained by suggesting that the sentences are connected to different deep structure strings.

The Emperor of Jupiter was delighted with Noam’s latest attempt, and the other Englishmen agreed that Noam seemed to have hit on a very good solution. He appeared to have devised a clear, economical system which was able to account for

all

and

only

the sentences of English, and which also captured the intuitions of the speakers about the way their language worked. A further important bonus was that the system could possibly be used for French, Chinese, Turkish, Arawak or any other language in the strange human world.

However, the Emperor was still somewhat puzzled. Had Noam explained to him how to actually

produce

English sentences? Or had he merely drawn him a map of the way in which related sentences were stored in an Englishman’s head? Noam was rather vague when asked about this. He said that although the map idea seemed nearer the truth, the map nevertheless had important implications for the way in which sentences were produced and recognized. The Emperor was extremely puzzled by this statement. However, he decided that Noam had done some splendid work, and so should be set free and rewarded handsomely. Meanwhile, the Emperor made a mental note that when he had some more spare time, he would have to contemplate more thoroughly the question of how Noam’s proposals related to the way humans produced and recognized sentences.

Let us summarize what the Emperor of Jupiter had discovered about the nature of human language and the type of ‘grammar’ which can account for it. First, he discovered that it is in principle impossible to memorize every sentence of a language, because there is no linguistic limit on the length of a sentence.

Second, he found that any collection of utterances must be treated with the utmost care. It contains slips of the tongue, and represents only a random sample of all possible utterances. For this reason it is important to focus attention on a speaker’s underlying system of rules, his ‘competence’ rather than on an arbitrary collection of his utterances, or his ‘performance’. Third, the

Emperor realized that a good grammar of a language will not only be observationally adequate – one which can account for all the possible sentences of a language. It will also be descriptively adequate – that is, it will reflect the intuitions of the native speaker about his language. This meant that a simple, left-to-right model of language, in which each word was triggered by the one before it, was unworkable. It was observationally inadequate because it did not allow for non-adjacent words to be dependent on one another. And it was descriptively inadequate because it wrongly treated all words as being of equal value and linked together like beads on a string, when in practice language is hierarchically structured with ‘chunks’ of words going together.

Fourth, the Emperor of Jupiter noted that a hierarchically structured, top-to-bottom model of language was a reasonable proposal – but it did not link up sentences which were felt by the speakers to be closely related, such as:

TO CHOP DOWN LAMP POSTS IS A DREADFUL CRIME.

and:

IT IS A DREADFUL CRIME TO CHOP DOWN LAMP POSTS.