The Beckoning Silence (23 page)

Read The Beckoning Silence Online

Authors: Joe Simpson

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #Outdoor Skills, #WSZG

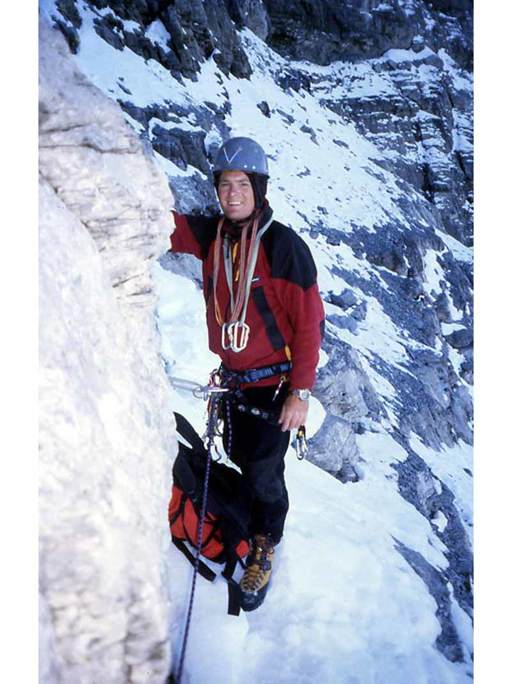

Ray at the Swallow's Nest.

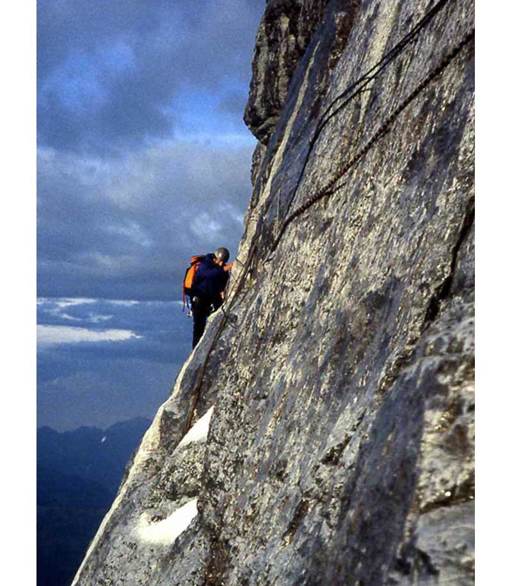

Ray dodging stone-fall while retreating across the Hinterstoisser Traverse.

Alpenglow over the Scheidegg Wetterhorn.

Joe at the Swallows Nest

Joe retreating on the Hinterstoisser Traverse

The North Face of the Eiger from the Kleine Scheidegg Hotel.

The Eiger looms above Kleine Scheidegg.

10 Against the dying of the light

As I drove slowly up the winding road twisting through a forest of pine trees I thought about what we had come to do.

You’re here now, kid. No turning back,

I thought and I was surprised at how calm I felt. I looked at the picturesque town of Interlaken built on the banks of the lake and surrounded by meadows and woodland. The landscape was astoundingly beautiful, almost unreal, since it was the sort of thing you saw on a chocolate box and never expected to see in reality.

I knew that soon the valley would open outwards as we approached the small hamlet of Grindelwald and there looming above it would be the immense north face of the Eiger. Friends had told me what an imposing and intimidating sight this was and how its vast dark shadowed wall could deter a previously enthusiastic north wall climber into wary submissiveness. I thought of all the Eiger books I had read over the summer, absorbing the countless photographs and the list of tragedies played out in full view of the watching tourists. I had constantly asked myself whether I wanted to be doing this and every time the answer came back, stronger and more positive with each time of asking.

Yes, I really do. I want to follow in the footsteps of those climbers.

It is how I had always climbed in the Alps, paying homage to the heroes I had read about by climbing their routes.

Reading the books had been my way of breaking down the psychological baggage associated with the wall. From every implacable story there was a lesson to be learned – when to turn back, where the dangers lay, what decisions to make – and I began to feel as if I knew the face intimately. I imagined all the things that could go wrong and then tried to decide what my best decisions would be – retreat or push on, sit out the storm or risk the stone-fall and avalanches of a descent. Sometimes I gleaned a little extra information that I knew might be vitally important and I stored it away in my memory for just such a moment.

I remembered reading Chris Bonington’s accounts of his early attempts on the face in his autobiography

I Chose to Climb.

Chris and the legendary Don Whillans had turned back from one attempt on the north face when they had reached the Second Ice Field. They had sensed that the weather was changing and realised that they still could safely make an abseil retreat down the Ice Hose and the First Ice Field to the shelter of the Swallow’s Nest. This eighteen-inch wide bivouac ledge sheltered by an overhang was perched spectacularly on the edge of a huge rock band. From there they could use the old fixed ropes, now routinely left in place, to reverse the Hinterstoisser Traverse and make their way slowly down the remaining 2500 feet of broken walls and ledges to the foot of the face.

It was from this point that Toni Kurz’s fateful party had struggled desperately to reverse the Hinterstoisser Traverse in 1936. The four-man party had reached the Death Bivouac, Max Sedlmayr and Karl Mehringer’s high point of the previous year – so called because it was here that Sedlmayr and Mehringer had frozen to death. On the first day of their climb Andreas Hinterstoisser had discovered what was to be the key to the climb and had brilliantly unlocked this crux rock barrier that gave them access to the heart of the face. When he and his three companions – Angerer, Rainer and Toni Kurz – had safely followed him across the glistening shield of slabby rock they retrieved the traversing rope that Hinterstoisser had so expertly fixed in place. From that point onwards the door back to safety was now locked behind them.

Despite desperate efforts Hinterstoisser couldn’t climb back across the traverse when they were forced to retreat, nursing Angerer who had suffered head injuries from a rock-strike. Hinterstoisser spent hours in frustrating and exhausting attempts to climb sideways across the glassy shield of rock that was now coated with a hard film of verglas.

The weather worsened and the rock-fall began spitting down accompanied by avalanches and waterfalls. Watchers at the telescopes in Alpiglen and Kleine Scheidegg could sense that a tragedy was beginning to unfold. The men were trapped. From the lower lip of the First Ice Field, adjacent to the Swallow’s Nest ledge, they attempted to abseil directly down the great rock barrier that lay between them and the easier ground of the lower face. This vertical rock face dropped beneath them occasionally jutting out in overhangs and roofs. The line of descent also lay in the path of torrents of rocks and avalanches, sweeping from the rim of the First Ice Field above them. Somewhere down on the icy rock wall lay the gallery windows – the great open holes tunnelled from the rock by the builders of the Jungfrau railway. This railway had been carved through the heart of the mountain to carry tourists up to the Jungfrau Joch, the col between the summits of the Monch and the Jungfrau. The gallery windows were positioned in the centre of the face and had been created primarily to dump rock spoil down the face from the excavations after 4 kilometres of tunnelling. Once the tunnel had been completed the gaping holes were developed into spectacular viewing windows for the hordes of tourists eager to look down the forbidding, ice-plastered precipices of the north face.

In 1936 the beleaguered party had tried to abseil directly down to a ledge that ran across the wall and which would with luck lead them to the safety of the Stollenloch, a small workers’ access window. They almost made it.

It was a bold decision in the days when abseiling was fraught with danger. Modern braking devices had not been invented and traditional friction abseils were used, winding the heavy, wet ropes across the back of the shoulders, around the chest and down between the legs to brake the speed of descent. It was precariously difficult to control. As Hinterstoisser and his three companions slid down through the tumult of avalanches and whistling stones Von Altmen, the Sector Guard stationed at the gallery windows, opened the huge wooden doors and looked out into the storm, searching for any sign of the retreating party. He was delighted to hear a cheery yodel. All was well despite the severe conditions. He ducked back inside to make a warming pot of tea for the young climbers who must have been exhausted after four days on the face.

Two hours later when no one had arrived he looked out of the window again. Conditions were more ghastly than ever, with mists rising from the abyss below as stones and slides of snow rushed down from the black emptiness above. This time there was no cheery acknowledgement to his shout, only the despairing cries of one man – Toni Kurz – shouting for his life. His companions were dead and he was hanging helplessly on the rope, spinning in space. Some dreadful calamity had caused Andreas Hinterstoisser to be swept from his abseil stance – a direct blow from stone-fall or an especially heavy rush of avalanching snow. Hinterstoisser had fallen the entire length of the face. Rainer had been dragged up by the weight of Kurz and Angerer who had been swept from their stance. Rainer, pulled tight against his karabiner clipped to the abseil piton, had frozen to death, unable to free himself. Below Kurz the lifeless body of Angerer swayed in the wind, strangled by his own rope.

A hurriedly organised party of rescuers managed to climb from the Stollenloch up 300 feet of iced rock slabs to a point 300 feet below where Kurz dangled. As night came on apace the rescuers realised that it would be impossible to climb up to the stricken climber directly. They told him to stick it out for the night despite his despairing pleas. It was an awful decision since they knew he would not survive the night unprotected from the savagery of the storm. In the dark, on that face, there was no one capable of the climbing feats required to reach Kurz. Not even the brilliant Hinterstoisser, one of the best climbers of his day, could have made such a climb.

Toni Kurz endured a long despairing night. For me, this was all that was hard, uncompromising, stern and nightmarish about mountaineering. It was a freezing, lonely night as he swayed on a slender rope, swinging backwards and forwards as the stones sang by and the icy gale lashed at him, bleeding the warmth from his body. Above him the rope played across the frozen corpse of his friend while beneath the wire-tight rope trembled as the wind swung Angerer’s corpse from side to side. All Kurz could do was endure. When at last morning broke the guides were astonished to find that the young Berchtesgaden guide was still alive and calling down to them in a strong, clear voice.