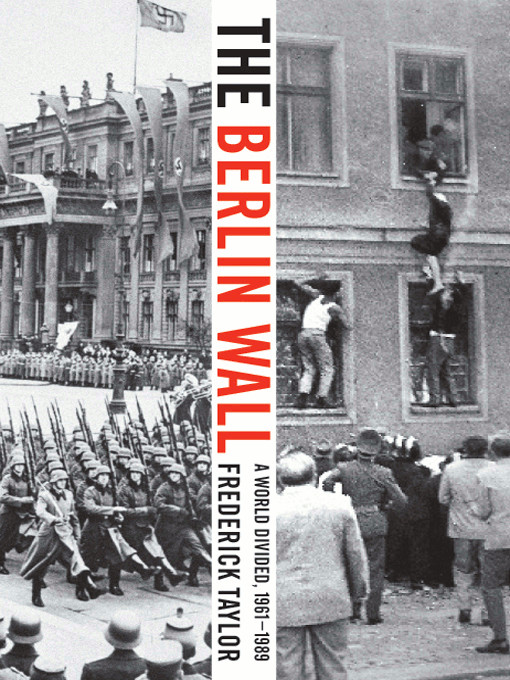

The Berlin Wall

Authors: Frederick Taylor

THE BERLIN WALL

A WORLD DIVIDED, 1961-1989

Frederick Taylor

CONTENTS

‘IT MUST LOOK DEMOCRATIC, BUT WE MUST HAVE EVERYTHING IN OUR HANDS’

‘DISSOLVE THE PEOPLE AND ELECT ANOTHER’

HIGH NOON IN THE FRIEDRICHSTRASSE

THE BARBED-WIRE BEGINNINGS

of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961 divided, overnight and with savage finality, families, friends, and neighborhoods in what had until 1945 been the thriving, populous capital of Germany. Streets, subway lines, rail links, even apartment houses, sewers, and phone lines, were cut and blocked.

The Wall represented a uniquely squalid, violent—and, as we now know, ultimately futile—episode in the post-war world. The subsequent international crisis over Berlin, which was especially intense during the summer and autumn of ’61, threatened the world with the risk of a military conflict—one that seemed as if it could escalate at any time to a terrifying nuclear confrontation between the US and the Soviet Union.

How did it come to this? In 1945, the victors of World War II—the USA, the Soviet Union, Britain, and by special dispensation the French—had divided Germany into four Zones of Occupation and its capital, Berlin, into four Sectors. Germany had been a problem ever since its unification in 1871, a big, restless country in the heart of Europe. The over mighty Germany of the Kaiser’s and Hitler’s time must, the wartime Allies agreed, never be allowed to re-emerge. With somewhere between thirty and fifty million dead in the bloodbath that Nazi Germany had inflicted on the world, it was hardly surprising that many in Europe and America went even further and demanded that it be kept disunited.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany, even as its surviving people strove desperately to feed and house themselves and to re-create some kind of viable economic existence, came the Cold War. From the late 1940s, Germany itself—what was left of it after the Poles and the Russians had carved chunks off its eastern territories—became a mutant creature of the new Communist-capitalist conflict. It divided into West Germany (the ‘Federal Republic of Germany’), a parliamentary democracy of some fifty million anchored into the western NATO alliance, and the much smaller East Germany (the ‘German Democratic Republic’), a more or less willing member of the Communist Warsaw Pact. By contrast with the increasingly prosperous West Germany, the GDR remained a struggling social experiment, a mere third as large. From the early 1950s, the ‘Iron Curtain’ ran through the middle of the former Reich, manifesting itself in a fortified border between the two Cold War German states.

Until 1961, however, Berlin represented a dangerous anomaly from the East’s point of view. Though a hundred miles inside East Germany, and surrounded by Soviet and East German forces, it remained under joint four-power Allied occupation and kept a special status, still more or less one city, in which fairly free movement was possible. Its porous boundaries represented a hole, an ‘escape hatch’ through which enterprising East Germans could head to the by-now booming West in pursuit of political freedom and a higher standard of living than their neo-Stalinist masters were prepared to allow them.

Between 1945 and 1961, some two and a half million fled in this way, reducing the GDR’s population by around 15 per cent. Ominously for the Communist regime, most emigrants were young and well qualified. The country was losing the cream of its educated professionals and skilled workers at a rate that risked making the Communist state totally unviable. During the summer of 1961, this exodus reached critical levels. Every day, thousands of East Germans slipped into West Berlin and from there were flown to West Germany itself along the so-called ‘air corridors’. The regime was not prepared to abandon the political and economic restrictions that fuelled the haemorrhaging of its brightest and best. Hence, on that fateful August weekend, the Communists’ vast undertaking to seal off East from West Berlin, to close the ‘escape hatch’.

Since the end of the war, Berlin had been a constant, running sore in East-West relations. In 1948-9 Stalin had tried to blockade the Western-occupied sectors into submission by closing off all the land routes into the city. The West surprised him with a successful airlift that kept their sectors supplied with sufficient essentials to survive. After a little under a year of siege, the Russian leader gave up. However, only Stalin’s death prevented a wall, or something very much like it, being constructed through Berlin in 1953. In 1958, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, every bit as aware of the city’s precarious position, started threatening West Berlin’s status once more. The ebullient, unpredictable Soviet leader compared the Allied-occupied sectors to the West’s tenderest parts. If, Khrushchev joked, he wanted to cause NATO pain, all he had to do was squeeze….

And on Sunday 13 August, Khrushchev squeezed. The day became known as ‘Stacheldrahtsonntag’ (Barbed-Wire Sunday). Within a few weeks this improvised wire obstacle started to morph into a formidable cement one, a heavily fortified, guarded, and booby-trapped barrier dividing the city and enclosing West Berlin.

The Wall shocked and amazed the world, a massive engineering and security project that before it was built many outsiders had dismissed as impossible. It extended for almost a hundred miles, with thirty or so of it dividing East from West Berlin, the rest sealing off the surrounding East German countryside. It was overseen by 300 watchtowers, manned by guards with orders to shoot to kill. The ‘no man’s land’ between East and West was littered with lethal obstacles, alarms, and self-activating searchlights, with an eleven-foot-high clamber-proofed slab fence representing the final, on its own near-insuperable obstacle. The structure would soon become notorious even in the farthest, darkest corners of the earth as the ‘Berlin Wall’.

Most Germans, of course, felt the building of this wall as a devastating blow. It was not just a brutal act in itself but also final proof, if proof were needed, that the reunification of their country that many still hoped for must remain a distant, even an impossible, dream. There was genuine outrage in West Germany, and also in the East, though this was rapidly suppressed by the Communist secret police, the infamous Stasi, who carried out thousands of arrests.

For Berliners, the drastic power-political surgery of 13 August 1961 was, of course, an especially tragic and painful experience. It was also a devastatingly intimate one. Familiar streets, parks, even individual buildings, were turned into perilous human traps, in which the squirming, helpless captives were often the westerners’ own friends and relatives. West Berliners were forced to stand by and watch—often literally—as their fellow citizens in the East, seeking to exercise a freedom of movement that most of us take for granted, risked their safety, their liberty, and in some cases their lives, to cross the Wall in search of economic and political rights that were not available to them on their own side.

Some of those imprisoned by the Wall managed to escape. Many died in the attempt. Many more were arrested, tried, and served long jail sentences, often under harsh conditions. I hope that those who live in more fortunate communities elsewhere in the world will summon up the imagination to conceive what it might have been like for Berliners to have such a barbarous fracture inflicted on their city, their neighborhoods, and their deeply rooted relationships. I have tried to tell their story in these pages, and to do justice to their courage and their determination when confronted with this deprivation.

Nonetheless, at a distance of years that is rapidly accelerating towards half a century since the Wall was created, it is a writer’s duty to reflect that changing perspective. One must treasure emotion and pity, but also measure these feelings against the incomplete but nevertheless clear shape of a political map that has finally begun to emerge from the violent, tragic fog of the twentieth century. Which is to say that the Cold War has been over for many years now, and is truly receding into history. It is time to re-examine, not the fact of individual and communal suffering that the Cold War caused, especially in Berlin—for that fact is indisputable—but to cautiously trace the more precise parameters of that suffering, and the way it fitted into the greater global picture.

Looked at in this more distanced and nuanced way, the building of the Wall, although it unleashed a brief East-West showdown, takes on a more complex appearance. Most ordinary Western civilians who watched the shocking and dramatic scenes from Berlin on their televisions sets, for this was the first international crisis to be properly televised, shared the horror of Germans and Berliners. However, behind the scenes—seen from a global and power-political perspective by those not directly affected—for the West’s political and military leaders, the building of the Wall was not necessarily the unalloyed catastrophe that it first appeared to the general public. Some would say it was almost as if a boil had been lanced.

So, was what happened that Sunday in August 1961 a problem that made the Cold War worse? Or was the Wall, in fact, not so much a problem as a solution?

There is little indication, it turns out, that any of the three major Western powers—the USA, under the recently elected President John F. Kennedy, or Macmillan’s Britain or General de Gaulle’s France—were decisively opposed to the division of Berlin. On the contrary, we now have considerable evidence that, since they could not reunify Germany in a way they could tolerate, the West’s leaders went along with the construction of the Wall. It was unpleasant and cruel, but it removed a continuing, serious danger to stability in Europe.

In effect, our governments, though in public they threw up their hands in fastidious horror—the Wall supplied, above all, an excellent propaganda weapon against the Communists—actually quietly abandoned the GDR’s seventeen million citizens to their fate.

That fate was for them to be held captive, for more than half a human lifetime, in a sealed country. The experience of East Germany’s population was made a little more tolerable by some basic social and welfare provisions and by a somewhat higher standard of living than elsewhere in the Soviet-ruled bloc, but it remained in most respects ugly, shabby, and bereft of hope and can only be compared to a form of collective incarceration.

This book explores how, through blood and sand, and then barbed wire and cement, this bizarre, closed world came into being. It tells how the leaders of the world reacted to this, and how ordinary people suffered, fought against, and survived the trauma. It recounts how for decades this prison-state enjoyed a foetid flourishing behind its fortifications. Finally, it celebrates the way in which how—just as quickly as it had arisen between dusk and dawn on 12/13 August 1961—during one unpredicted and unpredictable, extraordinary night a little over 28 years later, on 9/10 November 1989, the Berlin Wall and the world it had spawned met a sudden, exhilarating end.