The Bletchley Park Codebreakers (36 page)

Read The Bletchley Park Codebreakers Online

Authors: Michael Smith

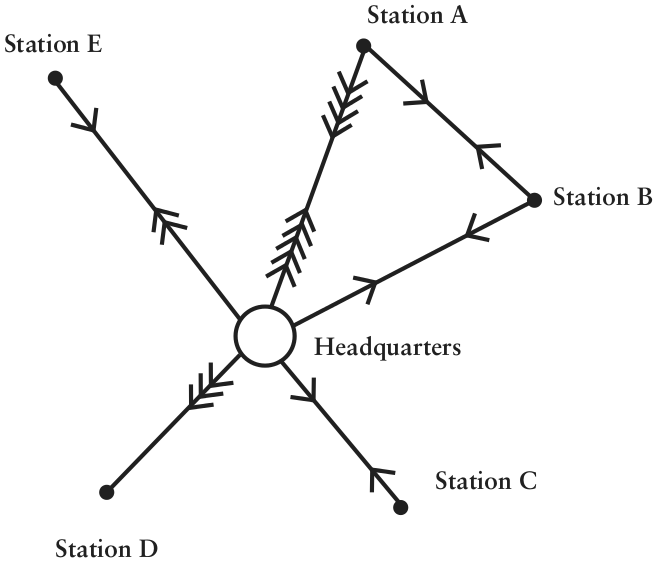

Figure 15.1

Network diagram showing the number and flow if messages passing between a headquarters and its outstations on a

Stern

(star) radio net.

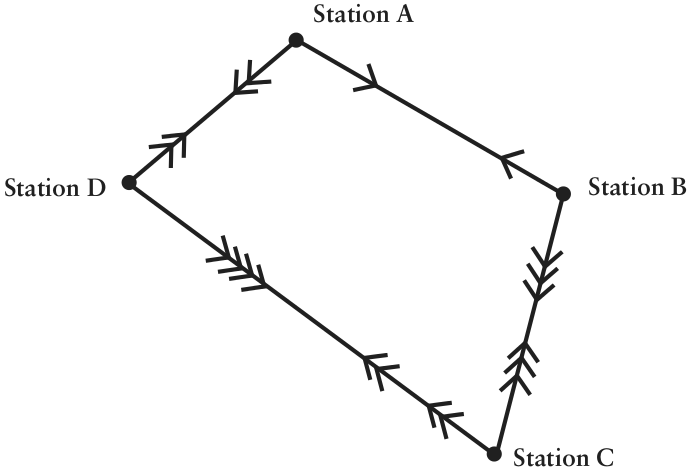

Figure 15.2

Network diagram showing the number and flow of messages passing between stations on a

Kreis

(circle) radio net.

Having written the weekly reports I would get a day off-duty, which I would spend perhaps in London, Oxford, Cambridge or Bedford. Trips to the theatre or the cinema, spending hours in the bookshops, a meal at my favourite restaurant, âAu petit coin de France', in Carnaby

Street, Soho, were always welcome breaks from the logs, call signs and frequencies. At times the working days were long and the nights were longer. It was always a relief in the middle of the night to down pencils, stumble across the park in complete darkness and enjoy a cooked dinner in the brightly lit cafeteria, thronged with men and women from other departments.

We log-readers, about fifty in number, mostly non-commissioned officers in the army, were not allowed to go into the Fusion Room. The officers, a few NCOs and some civilians who worked there would sometimes emerge to consult us about the traffic on the networks on which we were working; they sometimes asked questions about the weekly reports we had sent in. Activities were going on which, in the interests of security, could obviously not be revealed. Among ourselves we used to talk about these mysteries, wondering whether the German messages in cipher were being decrypted. But we toiled on in our blinkered fashion, blind to the wider picture known only to those working in the forbidden rooms.

We moved from Beaumanor to Bletchley Park on 3 May 1942. Several large army trucks carried us and all the office furniture and equipment from Leicestershire to Buckinghamshire. Here was another Victorian mansion set in extensive grounds, with formal gardens now ruined by the addition of long huts. Into one of these we unloaded our precious cargo. At the end of the log-readers' hut was another forbidden room out of bounds to us. Among senior staff at Bletchley Park there were some who thought that the log-readers should never be told that German Enigma ciphers were being decrypted. However, wiser counsels prevailed. It was decided that the work of traffic analysis would be more efficient if the log-readers knew more about the German networks they were studying. On 23 January 1943, Gordon Welchman therefore gathered all the log-readers together and told us the full story of the breaking of this machine cipher.

It was a memorable day for all of us, since our log-reading had often been a boring occupation. Now we had a new zest for the work, with access to a wealth of information about the German networks we were studying. Before we were told about Enigma we were trying to construct a picture with a jigsaw lacking many pieces; now we were allowed to see some of the English translations of German messages, which gave us information about who sent the messages, where they were located and what was their function.

The role of the Fusion Room, which was now a section of Hut 6, became clear to us. Its job was to fuse two lots of information. Workers in the room had to study all messages in German together with the reports of the log-readers. With knowledge of the whereabouts of any German transmitter, derived from direction-finding reports, it was possible to construct and keep up to date knowledge of German Army and Air Force networks and movements all over Europe and in other theatres of war as well.

The information revealed was of great help both to the cryptanalysts and to those concerned with guiding the intercept operators. The Fusion Room was able to warn the intercept stations about frequency and call sign changes so that operators could monitor the German stations and watch for changed locations, usually preceded by periods of silence when they moved around. The Fusion Room was staffed by civilians and army officers, male and female, and by some non-commissioned officers of both sexes, most of whom were commissioned later. During the war, fifty-six people worked in the Fusion Room for varying periods; of these thirty-one were men and twenty-five women. Thirty-seven of these arrived after the move from Beaumanor to Bletchley. As the German war expanded into the Balkans and later to North Africa the number of staff working in the Fusion Room increased. More men and women, some civilian, some army, arrived, most of them being fluent in reading German. American male army officers joined the Fusion Room later in the war and several American NCOs came to read logs.

When an Enigma cipher was not being decrypted, the Fusion Room was able to maintain a fairly complete picture by studying the reports of the log-readers, which revealed the quantity of traffic, call sign changes, and the routeing of messages. It also had the results of high-frequency direction-finding. This technique enabled us to locate German transmitters fairly accurately. To find a location all we had to do was to go to a small department at Bletchley Park, armed with the frequencies and the call signs of the stations we wished to locate. Major Firnberg's staff would then pass on the enquiries to Beaumanor, where a direction-finding exchange controlled many DF stations in the United Kingdom, ranging from the Shetlands to Land's End and Northern Ireland. These outstations established the direction from which the radio signals came by rotating an electrical device known as a goniometer until the signal came through at minimum strength.

The line bearings were then plotted on a map at Beaumanor. If three DF stations were used, the location of the transmitter was at or near any intersection of the three bearings. Locations were not accurate to a matter of a few miles, but they were near enough to be of great assistance to those who were building a picture of the enemy order of battle.

To avoid duplication of effort a reorganization of the work of traffic analysis took place in November 1943. From that date all parties worked together in Block G, one of the brick buildings provided when the original huts became inadequate. The Central Party was combined with other parties to form a new organization within Hut 6 called Sixta. The raw material, the logs from the red printed pads on which the operators wrote down in pencil everything they heard, arrived at Bletchley Park every day by despatch rider, unlike the enciphered messages which were teleprinted direct to enable the cryptanalysts to work on them urgently.

At Beaumanor, most of the log-readers â some fifty in number â were men. Soon after our move to Bletchley Park, more log-readers were recruited, many of them young women in the ATS. Several were in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), but we had no Wrens (members of the Women's Royal Naval Service). At its height, there were probably one hundred or more log-readers, from all ranks, from the lowly lance-corporal to the highest non-commissioned rank of regimental-sergeant-major. Among my fellow log-readers were teachers, barristers, librarians, accountants, journalists, bank clerks, parsons' daughters, undergraduates and graduates, male and female, who had recently completed their degrees or had interrupted their university courses.

As the war progressed we were all promoted regularly. I suspect this was partly to bring our army pay to the level of the salaries paid to the civilians, who were on Foreign Office scales. But whenever we were doing the same work, we were totally unconcerned with our different ranks. To those of us who had earlier experience of the crudities of army life it was good to be working with men and women in a friendly atmosphere, with little need for heavy discipline. For the most part we were on friendly terms with everybody. Indeed, some of us became lifelong friends. Several couples married. In my case I met a young subaltern who worked in the Fusion Room. In the days before we were married this led to no problems within Bletchley Park.

But when all military personnel were removed from their civilian billets and housed in a newly built army camp adjacent to Bletchley Park, administered by alien soldiers unused to our free and easy ways, the liaison between a subaltern and a company-sergeant-major was frowned upon.

All of us knew that we were a long way from the real war and we were far from the horrors of the Blitz. The perils of the 8th Army, slogging it out in Italy, the Soviet Army slowly overpowering the mighty German forces, the nightly departure of Allied bombers, some flying to their deaths â at times knowledge of these events made our log-reading seem a bizarre occupation. Yet, although we were only small cogs in an enormous war machine, the combined efforts of all those thousands of men and women who worked at Bletchley Park, together with the work of many others working in the intelligence services all over the world, were helping to win the war.

What was achieved can only be seen in the context of the whole picture. The intercept operators supplied our raw material. Our study of the traffic was combined in the Fusion Room with information from Ultra. The resulting detailed picture of German Army and Air Force formations over the whole of Europe and North Africa helped Hut 3's military and air advisers to prepare intelligence reports based on the decrypts, for transmission to British and American commanders in the field.

Sometimes we doubted the value of our work. It was heartening therefore to read in later years Gordon Welchman's views on traffic analysis at the end of his book

The Hut Six Story

, published in 1982: âI believe the Central Party that became part of the Hut 6 organization at Bletchley Park had more detailed knowledge of the entire communications system that handled Enigma traffic than anyone in Germany. It followed the movements, changes in control, retransmissions, the handling of different keys, and of course the chit chat that appeared in the logs.'

When the war with Germany ended on 7 May 1945, there were no more logs to read. But before many days had passed more logs appeared, this time from French and Russian traffic. Many of the log-readers, astounded to learn that we were intercepting Allied signals, refused to take part. We formed a group and protested. A captain whose name I do not remember attempted to justify the work, but we could not agree. âIn that case,' he said, âyou are redundant.'

Although we know a great deal about the activities of British intelligence during the Second World War, even now many details have still to emerge. This is largely a result of the unwillingness of secret services to give away either the identities of their agents, past or present, or methods of operation that might still be useful. But during the 1970s, two major intelligence successes were revealed. Sir John Masterman’s 1972 book

The Double Cross System in the War of 1939 to 1945

described how MI5 and, to a lesser extent, MI6, persuaded German spies to work for the Allies as double agents. They sent their

Abwehr

controllers intelligence that deceived them into believing that the main thrust of the D-Day landings would be against the Pas de Calais rather than Normandy and thereby ensured that the

Wehrmacht

was unable to drive the Allied forces back into the sea, as it had planned. It was not until two years later that Frederick Winterbotham’s book

The Ultra Secret

revealed the work carried out by Bletchley Park codebreakers. Winterbotham did allude to the part they played in Fortitude, the D-Day deception operation. But Masterman was unable for security reasons to mention Bletchley Park’s role at all. Yet the parts played by the double agents and the codebreakers were so closely intertwined that the Double Cross story can only properly be told when both are taken into account.

MS

The long-awaited opening of the second front in the war against Hitler came on 6 June 1944, now commonly known as D-Day. Senior administrators at Bletchley Park were well aware that some of the young men working there wondered whether they too should be fighting alongside their friends and relatives, who were now thrust into the thick of battle. Eric Jones, the head of Hut 3, the military and air intelligence reporting section, told his staff that the work they were doing was just as important. One recent report sent out by Hut 3 had shown that enemy dispositions in the Cotentin peninsula in Normandy had changed. US paratroopers had been due to drop right into the middle of a German division, with potentially disastrous consequences. The resultant change to their dropping zone saved the lives of up to 15,000 men, Jones said.

At this moment, in far the biggest combined operation in history, the first of the airborne troops are down. Sailors and airmen are facing frightful dangers to transport the first ground troops across the Channel and protect them on their way; more sailors and airmen are daring everything to blast holes in the German defences; and the ground troops themselves, in their thousands, will soon be literally throwing away their lives in the main assault by deliberately drawing enemy fire so that others may gain a foothold; and we are in complete, or almost complete, safety; some of us are even enjoying something akin to peace-time comfort

It’s a thought we cannot avoid and it’s a thought that inevitably aggravates an ever-present urge to be doing something more active; to be nearer the battle, sharing at least some of its discomforts and dangers. Such feelings cannot be obliterated but they can be subjugated to a grim resolve to serve those men to the very utmost of our capacity. There is no back-stage organization (and I think of Hut 3, Hut 6, Sixta

and the Fish Party as an indissoluble whole) that has done more for past Allied operations and Allied plans for this assault; and none that can contribute more to the development of the invasion once the bloody battles for the beaches have been won.

Jones was right. Although Hut 6 struggled with the

Heer’s

Enigma radio links during the early months of 1944, the British codebreakers still managed to solve most of the new

Luftwaffe

keys, and continued to break the indispensable main

Luftwaffe

key, Red. More importantly, a number of other sources allowed the intelligence analysts in Hut 3 to map out virtually the entire German order of battle in northern France. The most important of these was the enciphered radio teleprinter link between the headquarters of Field Marshal Karl Rudolf von Rundstedt, C-in-C West, and Berlin. Codenamed Jellyfish by the British codebreakers, it had been broken in March, following the introduction of the first Colossus computer. It produced detailed returns for each of Rundstedt’s divisions and, crucially, the itinerary of a tour of inspection of all the German armoured units by their commander General Heinz Guderian, updating the Allied assessment of the German military defences. This was already fairly good, based on traffic analysis, photo-reconnaissance and agent reports, as well as a detailed description by General Oshima Hiroshi, the Japanese Ambassador in Berlin, of a tour of the German defences in late 1943. An American working on the Japanese diplomatic machine cipher, known as Purple to the Allies, recalled the excitement of working through the night and into the next day on Oshima’s detailed rundown of the Atlantic Wall.

‘When I picked up the first intercept, I was not sure what I had because it was not part one,’ he said. ‘But within a few hours … the magnitude of what was at hand was apparent. I remained on duty throughout much of the day, continuing to translate along with colleagues who had pitched in to complete the work. I was too electrified to sleep. In the end, we produced what was veritably a pamphlet, an on-the-ground description of the north French defences of “Festung Europa”, composed dictu mirabile by a general.’

The gaps in Oshima’s assessment were filled in by two other messages sent from the Berlin embassy and deciphered at Bletchley

Park. Colonel Ito Seiichi, the Japanese military attaché, made his own tour of the entire German coastal defences at the end of 1943, sending a massive thirty-two-part report back to Tokyo. This was deciphered in a marathon six-month operation carried out by the Japanese military section at Bletchley Park and finished just in time for D-Day. The other message was a description by the Japanese naval attaché in Berlin of his own tour of the German defences in May 1944. Sent in the Coral machine cipher, broken only weeks earlier in a remarkable joint US–British operation, his report gave detailed appraisals of the German dispositions and intentions. Field Marshal Erwin von Rommel, who had been appointed to lead the main force resisting an invasion, intended ‘to destroy the enemy near the coast, most of all on the beaches, without allowing them to penetrate any considerable distance inland’, the naval attaché said. ‘As defence against airborne operations he plans to cut communications between seaborne and airborne troops and to destroy them individually.’

These were just some of the very many reports that ensured that by the beginning of June the British knew almost the entire disposition of the German forces awaiting them in northern France. Ralph Bennett, one of the intelligence reporters working in Hut 3, recalled that there was very little wrong with the British intelligence assessment:

Remarkably we got the positioning of all the German divisions. We made no mistakes, but you couldn’t make a mistake when you get a signal saying this division will be there. There’s no mistake we could make about that. We didn’t get exactly what one panzer division was going to do, which was to attack the left-hand section of the British landing, and we didn’t get the positioning of 352 Division, which was the one that held Omaha beach. We didn’t get the detail that it was going to be so close up and if we had we would have warned the American 1st Army that they were going to have a rather sticky time, otherwise we got it just about right.

This in itself was a major contribution towards the success of D-Day. But it was not the only one to be made by Bletchley Park, which played a key role in one of the most remarkable espionage operations of all time, the Double Cross system. The main credit for this system is normally given to MI5 and to a lesser extent MI6. But the role played by the codebreakers, and particularly by Dilly Knox, was absolutely crucial.

The Double Cross system originated from an MI5 plan based on an operation carried out by the French

Deuxième Bureau

. Dick White, a future head of both MI5 and MI6, suggested that captured agents of the German military intelligence service, the

Abwehr

, should be left in place and ‘turned’ to work as double agents for British intelligence. MI5 would be able to keep complete control over all German espionage activities in Britain and, as a welcome side-effect, the information the agents asked for would tell the British what the

Abwehr

did and did not know. At this early stage, this was the full extent of MI5’s ambitions.

One of the earliest opportunities to turn a German agent came with the arrest of Arthur Owens, a Welsh businessman who travelled frequently to Germany and who had volunteered in 1936 to collect intelligence for MI6. But the intelligence he provided was of little use and he was soon dropped. He subsequently got back in touch with MI6 to inform them that he had managed to get himself recruited as an agent by the

Abwehr

, claiming to have done so in order to penetrate the German intelligence service on behalf of the British. But interception of his written correspondence with his German controller threw doubt on this, suggesting that he was playing the two services off against each other. In September 1938, he announced to MI5 that he had now been appointed the

Abwehr’s

chief agent in Britain and that he had been given a special German secret service code with which to encode his messages. On the outbreak of war, he was arrested at Waterloo station and agreed to work as a double agent under the cover name of Snow. His controller was Lieutenant-Colonel Tommy ‘Tar’ Robertson of MI5, a remarkable man who was to become the key British figure in the Double Cross system, setting up an MI5 section (B1A) to run them.

Snow had been given a radio transmitter by the Germans in January 1939, handing it over to MI5 immediately. He had also been given a very primitive cipher with which to contact the Germans (see Appendix I). This was used to send Snow’s ‘reports’ to his German controller, and was also sent to Bletchley Park for evaluation. An alert MI5 officer, monitoring Snow’s frequencies to ensure that he sent exactly what he was told, noticed that the control station appeared to be working to a number of other stations. GC&CS was sent copies of the messages the station was transmitting, which were in a different cipher to that given to Snow. But the codebreaker who looked at them

expressed ‘considerable disbelief’ that they were of any importance, suggesting that they might be Russian telegrams originating from Shanghai.

Despite the scepticism displayed by Bletchley Park, the

Abwehr

radio nets were monitored by the Radio Security Service (RSS), which was run by Major E. W. Gill, a former member of the British Army’s signals intelligence organization in the First World War, and was based close to Bletchley at Hanslope Park. It had the services of Post Office intercept operators, plus a small army of volunteers, most of them radio ‘hams’, who scanned the shortwave frequencies looking for enemy wireless traffic.

Gill and a colleague, Captain Hugh Trevor-Roper (later Lord Dacre), who worked in the Radio Intelligence Service, the analysis section of the RSS based at Barnet, north London, broke one of the ciphers in use. They managed to show that the other messages on Snow’s allotted frequency were indeed

Abwehr

traffic. This appears to have been the source of considerable embarrassment at Bletchley and the row over the significance of the traffic went on for some weeks with Trevor-Roper becoming increasingly unpopular with the professional codebreakers. Eventually, a new section was set up at Bletchley, in Elmer’s School, to decipher the various messages on the network. It was headed by Oliver Strachey. The

Abwehr’s

cipher instructions given to Snow led to a number of ciphers being broken and the first decrypt was issued on 14 April 1940. Initially codenamed Pear, the decrypts became known as ISOS, standing either for Illicit (or Intelligence) Services (Oliver Strachey).

The ISOS decrypts enabled MI5 to keep track of the messages of the double agents and spot any other German spies arriving in the country. It also meant that the agents’ reports could be designed to allow the codebreakers to follow them through the

Abwehr

radio networks. Hopefully, this would help them break the keys for other ciphers that the German controllers were using to pass the reports on to Hamburg.

By the end of 1940, Robertson had a dozen double agents under his control. At the same time, MI6 was running a number of German spies abroad. ‘Basically, MI5 was responsible for security in the UK and MI6 operated overseas,’ said Hugh Astor, one of the agent runners. ‘Obviously there was a grey area as far as double agents were concerned because they were trained and recruited overseas and at

that point were the concern of MI6, while once they arrived here they became the responsibility of MI5.’

A ‘Most Secret’ committee was set up to decide what information should be fed back to the Germans. Its small select membership included representatives of MI5, MI6, naval, military and air intelligence, HQ Home Forces and the Home Defence Executive, which was in charge of civil defence. The committee was called the XX Committee, although it swiftly became known as the Twenty Committee, or more colloquially, the Twenty Club, from the Roman numeral suggested by the double-cross sign. It met every Wednesday in the MI5 headquarters, initially in Wormwood Scrubs prison, but subsequently at 58 St James’s Street, London. ‘The XX Committee was chaired by J. C. Masterman,’ said Astor. ‘Tar Robertson, who ran BIA, really developed the whole thing. He was absolutely splendid, a marvellous man to work for. He and Dick White were the two outstanding people I suppose and Tar collected around him some very bright people who actually ran the agents for him.’