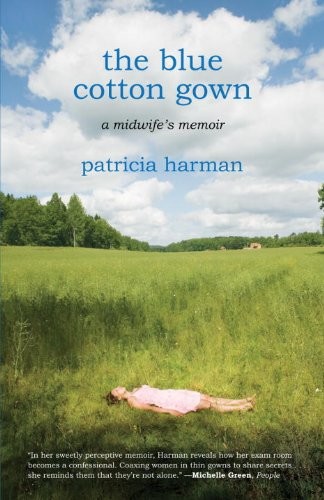

The Blue Cotton Gown

Read The Blue Cotton Gown Online

Authors: Patricia Harman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Medical, #Nursing, #Maternity; Perinatal; Women's Health, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

the blue

cotton go"Wn

a midwife's memoir

patricia harman

The Blue Cotton Gown

A Midwife’s Memoir

*

beacon press, boston

Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02108–2892 www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books

are published under the auspices of

the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

© 2008 by Patricia Harman All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992.

Text design and composition by Susan E. Kelly at Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harman, Patricia

The blue cotton gown : a midwife’s memoir / Patricia Harman.

p. ; cm.

isbn

978-0-8070-7289-9 (alk. paper)

1. Harman, Patricia 2. Midwives—United States—Biography. I. Title. [DNLM: 1. Harman, Patricia 2. Nurse Midwives—Personal Narratives.

3. Midwifery—Personal Narratives. WZ 100 H287 2008]

RG950.H36 2008 618.20092—dc22 [B] 2008007617

A portion of the first chapter originally appeared in the

Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health.

author’s note

The Blue Cotton Gown

is based on my experiences and stories told to me by my patients. All names, identifiable characteristics, details of time, and names of places have been changed for the sake of preserving confidentiality. Several patients, professionals, and staff are composites. The events and conversations described are how I remember them.

Heartfelt thanks to every precious woman who has shared her story with me in her thin blue cotton exam gown, and to every health-care provider who has persisted in his or her calling despite personal and professional obstacles. We each have our own story. This is mine.

Spring

Confessional

I have insomnia . . . and I drink a little. I might as well tell you. In the middle of the night, I drink scotch when I can’t sleep. Actually, I can’t sleep most nights; actually, every night. Even before I stopped delivering babies, I wanted to write about the women. Now I have time.

It’s 2:00 a.m., and I pull my white terry bathrobe closer, thinking about the patients whose stories I hear. There’s something about the exam room that’s like a confessional. It’s not dim and secret the way I imagine a confessional is in a Catholic church, the way I’ve seen them in movies. I peer at the clock. It’s now 2:06.

The exam room where these stories are shared is brightly illuminated with recessed lighting. The walls are painted off-white and have a wallpaper border of soft leaves and berries. There are framed photographs of babies and flowers and trees, pictures I took myself and hung to make the space seem less clinical, and a bulletin board with handouts on stress reduction, wellness, and calcium.

The room is not big. It’s the usual size. If I had to guess, I’d say eight feet by ten feet. The countertop under the tall white cupboard is hunter green, and there’s a small stainless-steel sink in the corner. Other than a guest chair, my rolling stool, and a small trash can with a lid, there’s just the exam table, angled away from the wall, with a flowered pillow and rose vinyl upholstery. On it lies a folded white sheet and a blue cotton gown with two strings for a tie. The exam table dominates everything.

I don’t drink for fun. I don’t even like scotch. It’s for the sleep. I can’t work if I can’t sleep. The scotch is my sleep medicine and I want it to taste like medicine. The little jam jar with the black line at three ounces sits in the bathroom cupboard. My husband fills it for me, then locks the bottle in the closet. I ask him to do that. When you have as many alcoholics in your family as I do, you don’t take chances. On nights when I’m restless, I drink it down sip by sip, making a bad face after each swallow. Then in an hour, I go back to bed.

I stand now at the window listening to the song of the spring frogs and thinking of the stories the women tell me, and then, in the stillest part of the deep night, I sit down to write. I need to sleep

. . . but I need to tell the stories. The stories need to be told because they are from the hearts of women; the tender, angry hearts; the broken, beautiful hearts of women.

heather

It’s Monday morning and I’m late again. Waving to the receptionists, I rush through the waiting room. They turn to greet me in their aqua checked scrubs but keep on with their work. I know they keep track of how often I’m tardy.

“Hi, Donna,” I say as I pull open the heavy cherry door to the clinical area. Donna, at the checkout desk, looks over her sleek horn-rim glasses and gives me a smile. The phone is tucked under her ear and she’s clacking away at her computer.

Around the corner and down the hall is my office. It’s small, just enough room for a desk, a file cabinet, two bookcases, and a guest chair. The cream walls are lined with my photographs: the highland forest in full autumn color, a pregnant woman stepping out of the shower, and our barn with the red roof next to our cottage in

Canada. On the window ledge are purple African violets rooted in a green pot that Tom threw on the wheel in his studio and a framed photo of the five of us last Christmas. I toss my briefcase into the corner.

In the picture, three mostly grown boys, Mica, Orion, and Zen, clown in front of the slightly crooked spruce tree. That’s me in the back, with round pink cheeks, short straight brown hair streaked with gray, and wide blue eyes; a tall, girlish, middle-aged woman. Tom, stocky, slightly balding, with wire-rim glasses and short gray hair, stands with his arms around me. He’s laughing too. It would take a miracle drug to get us all looking normal in front of a camera.

The Women’s Health Clinic is located in Torrington, home of Torrington State University, on the fifth floor of the Family Health Center. Our private practice is composed of Tom Harman, ob-gyn; our two nurse-practitioners; and a staff of seven nurses and secretaries, all women. The suite, which we designed ourselves, is arranged in a rectangle with nine exam rooms, five offices, a lab, and a conference room. There’s also a small kitchen, the waiting room, and the large secretaries’ area up front. On two sides, windows run the length of the office. I wanted the staff and the patients to be able to look out at the sky.

Five minutes after I arrive, I’m standing in the exam room holding out my hand to a skinny young woman who stares at it as if she’s just been offered something she’d rather not touch, a dead fish or rotten banana. She has short curly red hair, a beautiful girl, but she holds her head down like she doesn’t know it. An eyebrow ring mars her perfect face. I pull my hand back and try again. “I’m Patsy Harman, nurse-midwife, you must be . . .”—glancing at the new chart—“Heather Moffett.”

Heather doesn’t say hello or anything else. There’s also an older woman and a young man in the room, so I start talking to them, turning first to the older lady who’s sitting in the guest chair, clutch-

ing her large white pocketbook. “And you are . . . family?” The grim-faced, gray-haired woman nods once. She inspects me through her glasses, clear plastic frames with rhinestones at the corners.

I was hoping she would introduce herself. “Heather’s mother or aunt . . . ?” I prompt. It’s always better to flatter than insult, though the woman appears to be in her seventies.

“I’m her grandma.”

This is not a cordial group, and I’m wondering what kind of conversation they were having before I came in. The air feels like ce-ment just beginning to harden. “And you?” I turn to the young man.

“T.J.,” he responds sullenly. That’s all he says.

Heather is sitting hunched over on the small built-in bench in the dressing corner of the exam room, her arms tucked into her blue exam gown. T.J. swivels back and forth on my stool. The grandmother is perched on the one gray guest chair, so there’s nowhere left for me to sit except the exam table, and that isn’t going to happen.

“Before we get started, let’s rearrange things,” I say energetically. “Heather, you sit up here on the exam table. T.J., you sit where she was, and I’ll take the stool.” We all trade places and when the young man stands I realize he’s over six feet tall. His hair reaches past his shoulders and he’s good-looking, like a heavy-metal star in the eight-ies, thin and sensuous with flat gray-blue eyes. No one says anything. They just move to where I point.

“So.” I start up once more. “It looks like you’re going to have a baby, Heather. Were you trying, or did it just happen?” I ask it like this, not wanting to assume every teenage pregnancy is an accident. Heather shrugs and glances at T.J.

I try again. “So are you excited, or still in shock?” “Excited, I guess,” Heather says, not sounding like she is.

“Well, that’s nice, then,” I respond. The grandmother rolls her pale, watery blue eyes and crosses her ankles, which look purple and sore.

“Let me go over what you’ve written in your history, and then I’ll

ask you more questions. Today what we need to do is an exam and some lab work—” I don’t get to finish.

“I got to puke,” says Heather, standing up with her hand over her mouth and searching wildly around. The grandmother and I stand up too. The older woman opens her bag and comes up with some tissues. I take Heather’s slender arm and lead her to the small stainless-steel sink. T.J. stays where he is. This doesn’t involve him. Heather gags.

“Do you have time to get to the bathroom?” I ask. The patient stands still, her head down, her red hair hanging around her face. I pull the curls back, holding them out of the way. Nothing comes up.

“I’m okay . . . I think,” Heather whispers. “Has she been vomiting a lot, Mrs. . . . ?”

“It’s Gresko, Mrs. Gresko. A fair ’mount, yes. Three, four times a day, seems like, maybe more.”

I take the girl’s pulse. It’s rapid, and when I pinch the pale skin on her forearm, it tents, a sign of dehydration. “Are you keeping

anything

down?”

“Some,” says the grandmother. “She’s bleeding too.” Our eyes meet, and when I look over, I see blood dripping down Heather’s legs.

“When did this start?”

“Yesterday. That’s why we called ’round for an appointment. I don’t want nothin’ to happen to this baby.”

So much for taking a detailed, organized history. “You know, Heather, I’ve changed my mind. I’ll read what you wrote on the OB form and ask you questions next visit. Since you’re feeling so sick, I’d just like to get you a prescription for the vomiting and—”

“What about the blood?” T.J. challenges. “That isn’t good, is it?” “No, it isn’t. It isn’t a good sign, but it doesn’t always mean something bad. How much blood is there?” Heather looks at her grandmother.

“ ’Bout like her monthly,” Mrs. Gresko says.