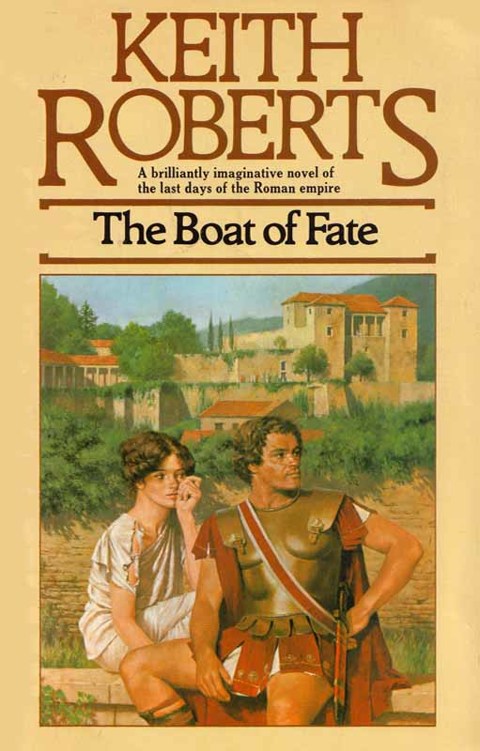

The Boat of Fate

Keith Roberts

Copyright © 1971 by Keith Roberts

First published 1971 by Hutchinson & Co. Ltd., London. Coronet edition 1975

ISBN 0 340 18805 7

With the exception of actual historical personages, the characters are entirely the product of the author’s imagination and have no relation to any person in real life.

For Crearwy who ate honey

Chapter One

For many evenings now I have sat patiently, scratching away at a ragged mass of memories. It seems the time has come finally to reduce what I have committed to an order; to give it shape, and a certain logic and progression. Not such a shape, perhaps, as the least of our poets could achieve; I am no author, and make no pretensions along those lines at all. But I have had a full and varied life; I have known despair, terror and joy. Something of that joy I want to set down, to be a spark against the darkness that is surely coming on the world.

Above me the lamp, hanging from its bronze chains, casts a mellow circle of light. Beyond that circle, at its wavering outer edge, hover the ghosts I have raised; beyond them again is the dark, symbol perhaps of that greater Night. Soon, I shall seek my bed; but for a while, who knows? Perhaps the Muse will condescend to rustle her robes a little closer to the Earth.

I am Caius Sergius Paullus. I was born in Hispania in the reign of Valentinian, that Pannonian clown who thought the world was made to benefit barbarians. I was a babe in arms when he died, unlamented, of a stroke; when I was five Theodosius, whom men already call The Great, was raised from his estate in Tarraconensis to be the new saviour of the world.

As one grows older so the easy convictions of childhood become more blurred; and I suppose I of all men should be the last to criticise an Augustus. But I can find little good to say of Valentinian. I’ve heard he was an efficient administrator; but as far as that goes any Tribune of a Schola, raised suddenly to the Purple, might have done as well. He was a peasant, like his father before him; and nobody is as merciless as a freedman who has happened on authority. He it was who vulgarised the Empire, first decimating the Senate with his purges, then making their numbers up by granting the clarissimate to any of his thick-headed friends who happened to catch his eye. Some of these oafs rose to be Governors of Provinces; and the West laughed, since there was nothing else to do. If the West laughed, the barbarians laughed; and losing their respect for us, also lost their fear. Under Valentinian, the floodgates started to creak; and not even Theodosius could finally stem the tide that burst through.

But it made little difference to us in the far south-west who lorded it in Mediolanus or Rome. In my childhood both Hispania and Gaul were much disturbed, owing forced allegiance to Magnus Maximus, one-time Governor of Britannia and self-declared Augustus. The jockeyings for power among the various factions were complex and endless; we kept our heads down, paid our tax and hoped for better times.

In those days Hispania was still a wealthy Province; indeed Baetica, in which stood my home town of Italica, had been called, like Egypt, the granary of Rome. Our wines were famous, while Hispanian horses fetched good prices anywhere in the Empire, being faster and smoother in action than the celebrated mounts of Persia. It was through the breeding of horses that my mother’s family had first risen to eminence, and the status of curiales; so it was no disgrace when my father mingled the blood of Roma with the blood of a Celt.

My mother had a Christian name, a given name, Maria; but it is by her true name, Calgaca, that I choose to remember her. The Bishop of Italica gave it to her, sprinkling her with water and making her swear to follow the true God and his faithful Church. She was very sick at the time, having nearly died in bearing me. My father, like the great Constantine, was content to remain unpurified, having agreed to undergo the ceremony on his death-bed when opportunities for mortal sin were past.

All Hispania was strong for Christ in the days of my youth. Bishops proliferated, so that Baetica alone laid claim to twenty; though as my father once remarked all of them seemed more concerned by heresy within the Church than paganism without. Our hillmen of the north, our Galicians and Cantabrians, still worshipped, as they had always worshipped, what Gods they chose; and some of their methods were most woefully unholy. Meanwhile the Church of Hispania was split by schisms, many of the Bishops rallying to the cause of the zealot Priscillianus; to such good effect that much worthy blood was spilled before that energetic and misguided man was finally executed by the mock Emperor Maximus. Not so much, as my father pointed out, for consorting with lewd women, apparently a human and forgivable aberration, but for presuming to invoke the Almighty without the benefit of his breech-clout; my father, as you will have gathered, was a bitter and sarcastic man.

Like most of the towns of southern Hispania, Italica was surrounded by tolerably high walls. Beyond the gates stretched plantations of olive and orange trees, while the land round about was dotted with the farms and country houses of the wealthy. On market days the little forum would throng with shoppers and mendicants, peasants from the outlying districts with their produce, pedlars of rugs and furnishings, pottery, jewellery, iron and bronzeware, lamps, statuettes. Smiths displayed their wares, waggon-and wheelwrights shouted their skills one against another, perfume-sellers set out their bottles and jars; most things, vendable, wearable or edible, found their way finally to the market-place of Italica.

There were soldiers, too, on leave from duty with our one Hispanian Legion; and not infrequently barbarians in the service of Maximus or Theodosius, proud, stinking men who spoke clacking tongues of their own. They thronged the colonnaded walks surrounding the forum, where the businessmen and officials of the town, my father among them, had their offices; or they would wander across to stare curiously at the long basilica flanking the market-place, the building where once justice had been dispensed and judgements made, long since re-consecrated in the name of the Christian God. Beyond it were more shops, set in narrow side alleys, where drinks, pastry and sticky sweets could be bought or acquired for small services, the running of errands, delivery of goods to customers living outside the walls. Here, too, in this busiest quarter of the town, stood the house in which I was born.

Its entrance was narrow, squeezed and jostled on both sides by the facades of shops. One was a wine-sellers, run by an aged and cranky African who had looked the same as long as I could remember. All day long, and a good part of the night, he would shout his wares in a croaking voice, while his consort, an equally ancient Negress, alternately fussed with the tall jars that held the stock, each with its stopper and leaden vintage seal, or beat a species of doleful accompaniment on the pots and vessels with which one wall of the place was lined. The old fellow loathed children with an abiding hatred; he would drive them from the shop, or the pavement before it, with cuffs and shouts, muttering between times a series of curious oaths taken by most of us to be peculiarly withering spells. My father was his landlord; so with me he adopted a slightly more subtle technique. Were I to pause before his establishment either he or his wife would instantly appear, wielding an enormous broom with which they proceeded to dust the stone flags of the pathway. I would be shooed aside, rather like a fly brushed from a joint of meat, and, unless I skipped pretty smartly, with a well-barked shin or two for my pains. In time I learned to avoid both the virago and her master, contenting myself with taunts muttered at what I deemed a safe and suitable distance.

On the other side of the porch was a bakery run by a Syrian, a fat, wheedling, olive-skinned man with a high-pitched voice and a truly remarkable squint. The legitimate sale of bread and pastry formed only a small part of his income, if the gossip of the town was to be believed; he was a notable procurer, both of young women and boys, and despite the undoubted value of his services he was heartily disliked in Italica. Some of his team of young acrobats worked in the shop, sweating over the ovens or grinding away at the big cornmills that stood against the rear wall; their rumbling penetrated the house, reaching to the atrium and beyond. However, Septimius, as he styled himself, usually seemed anxious to keep on good terms with me; most times, if he saw me passing, he would waddle from the shop, press on me a bag containing pastries, piping hot and fresh, twirled sometimes into shapes like curious little mannikins. He was frequently to be seen about the town and market-place, stertorously taking the air or unobtrusively touting for trade.

My father’s house, though small, was well proportioned and excellently maintained. Like all our Roman houses, except the homes of the very poor, it was externally featureless. The doorway was narrow, as I have said, and closed by two heavy bronze-studded valves that creaked abominably on their pivots as they turned. Beyond, the place was of classical design, its rooms and offices grouped round the open-roofed areas of atrium and peristyle. The atrium was curious in that there was no central catchment tank for rainwater; instead the roof-eaves sloped outwards, the water draining through hidden conduits to an underground storage system. Though undeniably less elegant, my father considered the arrangement more hygienic; he set great store by such things, and was always concerned to see the housepeople were kept up to his own exacting standards.

Sleeping cubicles, each paved traditionally with white mosaic, opened from this forecourt of the house, while to one side stood my father’s massive iron-bound safe. It contained little of real value; just some family papers, and a couple of dusty and much battered masks of ancestors. I remember as a child how terrified I was of them. On feast days, according to ancient custom, they were taken out, furbished and displayed; I would skirt the alcoves in which they were placed, if possible with eyes averted. Looking back there seems little to have inspired such fear; one represented a stern-faced, beak-nosed man with a squint not unlike that of old Septimius, the other was of a woman with an odd piled-up hairstyle and a fatuous, rather wooden grin. In fact one of the housepeople--probably Marcus--muttered once that in his opinion they had nothing to do with the history of the family but had been picked up as a job lot at some auction of the trappings of a temple. I am inclined to believe they were genuine, whoever they represented, for my father was moved to quite extraordinary rage when the tale was carried to him. Soon after that the custom of displaying them was discontinued anyway, and I never saw them again; for the good Bishop of Italica at last condemned the practice as idolatrous, and my father, as a man very much in the public eye, was forced, grumbling bitterly, to defer to the strictures of the Church.

Beyond the atrium an opening, wide and high and generally closed by richly decorated drapes, gave on to the garden of the peristilium. Here roses and lilies stood in carefully ordered rows; and here too were many fountains, filling the place with their lilt and splashing chuckle. Water supply was my father’s profession, but it was also his hobby. If complimented on his garden he would usually remark that though money might have vanished from the scheme of things, fountains at least were free.

A colonnade ran round the peristyle, giving shelter on all sides from rain and the direct heat of the sun. More rooms, my father’s study and the family sleeping cubicles, opened from it; beyond it the triclinium, a long narrow chamber flanked by its attendant kitchens, terminated the house.

Before the screen wall of the triclinium, placed on a pedestal where it could watch back through the house, stood a most curious bust. My mother commissioned it, from a wandering Ceard; a slim, corn-brown man who laughed and chattered as he worked in the singing, lisping tongue she would never use. Though as he spoke she smiled and nodded, and once the tears came suddenly to her eyes and she brushed them away and smiled again like sun after rain. I was very small at the time; I crouched at her knee as the stranger tapped and chipped, darting forward now and again to catch the fragments of stone as they fell or were brushed from his work. I was ranging them on the flags of the courtyard, pretending they were armies of Romans and Persians drawn up to do bloody battle, for I was already imbued with a sense of the history and destiny of my father’s people.

The statue was intended as a likeness of that Virgin who the Bishop assured us had been the Mother of God; but the strange eyes, mere holes above the gash of a mouth and the half-existent nose, the full face and profiles separate yet curiously joined, were like nothing I or the household had ever seen before. My father detested the carving, though he suffered it to remain. The housepeople were afraid of it. Even Marcus shook his head over it and muttered that he had seen its like only once before and that on the Wall, the great Wall the Emperor Hadrian built to mark where the last Standards were to rest, on the grim edge of the world. Which was curious, for I learned afterwards the craftsman had indeed hailed from Britannia.