The Book of Lost Books (11 page)

Origen

{

c.

185â254}

ORIGEN, THE GREATEST of the early exegetes of Christianity, freely admitted that even he had, on one occasion, grievously misinterpreted the Bible. Reading the Gospel of St. Matthew, chapter 19, verse 12, he had taken rather too literally the phrase “and there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake. He that is able to receive

it,

let him receive

it,

” and castrated himself. In terms of his career this was bad enough, as his admission to the priesthood was repeatedly questioned on account of this self-mutilation; in terms of his scriptural hermeneutics, it was an embarrassing lapse into reading as verbatim a text that was deeply allegorical, anagogical, metaphorical, and mystical in its import.

Origen was born in Alexandria into a Christian family. From an early age, he displayed an almost excessive zeal for reading scripture, to the extent that his father, Leonides, in a rather touching anecdote recorded by Eusebius, would kiss his son's chest as a sanctuary of the Holy Spirit. Leonides was executed in 202 under the purges of Emperor Severus: no doubt this deeply affected Origen's theology. At the age of only eighteen he became the head of the catechetical school in Alexandria, preparing candidates not only for baptism, but for the possibility of martyrdom. He sold his beautiful editions of the Greek philosophers and poets in order to support the familyâa decision he may later have rued.

His intellectual skills were soon applied to weightier matters than the simple induction of new converts. “I was sometimes approached by heretics and people educated after the Greek model, particularly in philosophy,” he wrote. “I therefore thought it advisable to make a thorough study both of heretical doctrine and of the philosopher's views about the truth.” A school began to form around Origen, where he encouraged the students to “read all philosophy without preferring one . . . or rejecting another.” Except for the atheist Epicureans, “nothing was kept from us, nothing concealed or made inaccessible. We could learn any theory, barbarian or Greek, mystical or moral,” recorded one student, Gregory of Nyssa.

Some students converted to Christianity, others merely improved their moral conduct. In effect, Origen was embarking on a massive liberal program of education that would have far-reaching consequences for the church, and equip him for the most intensive theological battle of his career. Listening to other philosophies had an immediate pragmatic goal: as Origen sagely observed, the established schoolsâStoicism, Platonism, and so forthâfound it difficult to effect change. “They never listen to those who think differently . . . that is why no old man ever succeeded in persuading any of the young.” In the intellectual melting pot of early third-century Alexandria, Origen had the opportunity to immerse himself in vastly different philosophies. “All wisdom is from God,” and the Christian scholar winnowed the errors from the inspired pagans.

Origen's fame as a philosopher, textual critic, and preacher won him praise from his adversaries, even from Julia Mamaea, aunt of the Emperor Heliogabalus. Seven amanuenses transcribed his sermons, although his

Commentary on St. John

was preserved in an imperfect Latin translation by Rufinus, who often “supplied the missing threads . . . readers would not stomach his habit of raising questions and leaving them in the air, as he often did when preaching.” Origen's eight-volume

Commentaryon Genesis

is lost, as is Rufinus' text, and the

Commentary on

XXV Psalms

is a handful of fragments.

Origen left Alexandria in 230 because of a dispute with his bishop, Demetrius. He was accused of preaching without being a priest, and then of becoming a priest in Palestine despite being a castrato. Finally excommunicated, he settled in Caesarea, where he participated in ecclesiastical councils, corresponded with other scholars, and, eventually, was tortured in the resurgence of anti-Christian edicts under the Emperor Decius.

There, he also completed his major work,

Against Celsus.

Celsus was a prominent Platonist scholar who, around 180, had written a major philosophical diatribe against Christianity entitled

On the True Doctrine.

Although seventy years old, the attack was still sufficiently pertinent for Ambrosius to encourage Origen to consider a rebuttal. Without Origen's retort, we would know nothing of Celsus at all.

Christianity had been attacked before, by satirists like Lucian of Samosata and the orator Fronto, but the basis of the criticisms had been so hyperbolic (ritual murder, atheism, cannibalism) that the earlier theologians, Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Clement, had concentrated on suppressing internal division, heresy, and unorthodox teachings, rather than parrying criticism from outsiders. Celsus' polemic was of a different order, and required a more substantial retort.

Against Celsus

is the first true work of Christian apologetics.

Celsus'

On the True Doctrine

is lost, but its substance can be inferred from the frequent quotation Origen deploys throughout his counterattack. Scholarly estimates have presumed that anything between 50 and 90 percent of Celsus' treatise has been ossified in Origen's work, though it would seem uncontentious that Origen would not choose to quote any hypotheses he could not disprove.

What is evident is that Celsus had a certain gift for vituperation. In deliriously caustic prose he castigates the new religion: it is for “sinners, the stupid, the childish and, not to mince words, outcasts of all kinds . . . if you wanted to form a gang of thugs, who else would you ask to join?” Jesus was a two-bit street magician, the apostles were “miserable publicans and sailors,” and the only evidence of the resurrection came from a “fanatical woman.” Entertainingly arch though this is, it allows Origen to undermine him with considerable elegance. Each mocking exaggeration is held up to calm correction. Christians may evangelize sinners; does Celsus believe that there is anyone who has not sinned? Though Celsus mocks Jesus for allowing his own betrayer to become a disciple, Origen counters that even Celsus' beloved Plato was intellectually betrayed by Aristotle.

When Celsus points out parallels between classical and Christian mythology, such as the similarity between Deucalion and Noah, arguing that this new religion is merely derivative, Origen retaliates with an impassioned defense of the allegorical nature of scripture. Adam is not just a literal forefather, but the condition of all mankind. The new religion has more truth, even if the Greek versions have more beauty.

Even if Origen did not introduce the concept of nonliteral reading into biblical exegesis after the incident with the knife, he certainly perfected it. In his commentaries on St. John, he addresses head-on the contradictions between John and the other evangelists. Such inconsistencies were deliberately present in the text like hermeneutic distress flares. The Holy Spirit allowed them to shock readers out of acquiescence and force them to consider the symbolic levels of the narrative. This manner of reading the Bible is an unquestionably profound legacy.

Origen did not die during his torture, but soon afterward; thereby he was denied his longed-for status as a martyr. After his death, many of his works were banned and destroyed, particularly since he seemed to subscribe to an unorthodox belief (that God's power was so great that, should He wish it, He could even redeem Satan) that ran against notions of election. Having been excommunicated in life, he was eventually deemed heretical in death. His works were destroyed, and the most substantial remnant twins him perpetually with the pagan Celsus, each forever preserving and subverting the other.

Faltonia Betitia Proba

{

c.

322â

c.

370}

IN HER ONE extant poem, Faltonia Betitia Proba informs us of the other poems she had written:

Once I wrote of leaders violating sacred truths Of them who cling to this terrible thirst for power.

She had concerned herself with “the spectacles of trivial themes . . . horses, arms of men and their wars.” More specifically, she had written a panegyrical epic on the defeat of the usurper Magnetius by Emperor Constantius II. It was at a time when her husband, Adelphius of the Anicii, would have appreciated her public show of support. The emperor and his brothers and corulers, Constantine II and Constans, had found that dividing the empire led to a multiplication of problems: in the early 350s, Constantius II had faced four separate rebellions. When Adelphius was elevated to the post of prefect in 351, loyalty was at a premium.

But we cannot be sure about Proba's description of her lost works, since the poem in which she alludes to them is an example of a very peculiar genre: the cento, which means that Proba did not actually write any of the lines of her poem.

A cento is a patchwork, where the writer rearranges lines by another poet to create a wholly new poem. Proba's

Cento

shuffles 694 lines of Virgil to narrate a Christian history of the world, from the creation to Christ's resurrection. Tradition has it that she composed the work in an attempt to convert Adelphius, showing the immanence of God's truth even in his beloved pagan authors. She describes the deity in this manner:

When He saw them all shining steadfast in the clear skies (Virgil,

Aeneid,

book 3, line 518)

The Almighty gave his name and numbers to the stars (Virgil,

Georgics,

book 1, line 137)

And the year was divided into four equal parts (Virgil,

Georgics,

book 1, line 258)

Centos were a popular form. Ausonius composed an epithalamion version for the nuptials of ValentinianâH. J. Rose describes how “by a process of collocation, totally innocent phrases of the poet are twisted into indecent meanings.” The poet Hosidius Geta, according to Tertullian, had created a whole tragedy about Medea using the method. Theoretically, if any cento's ur-text exists, and we knew the length of a lost cento, it would be possible to re-create it from the works of Virgil.

Suppose, for example, that Proba's

Cento

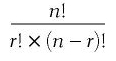

had joined her other works in oblivion, but a passing mention in a minor commentator retained the information that it had been 694 lines long. The number of possible permutations is given by the factorial formula where

n

denotes the size of the sample from which the lines are drawn, and

r

is the length of the finished work. This is a factorialâfor example, factorial 3 (3!) is a way of expressing 3 Ã 2 Ã 1; similarly factorial 7 (7!) is 7 Ã 6 Ã 5 Ã 4 Ã 3 Ã 2 Ã 1.

Using the dimensions of Proba's

Cento,

we would have to calculate very large factorialsâ12915! divided by the product of 694! and 12221!.

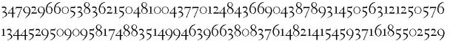

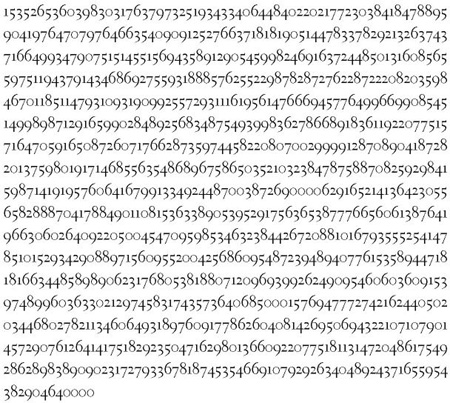

Thus, the number of combinations is:

âwhich hugely exceeds the number of atoms in the universe. Moreover, our formula does not take into consideration that the

order

of the lines is also important: it treats the combinations (

a, b, c

), (

a, c, b

), (

b, a,

c

), (

b, c, a

), (

c, a, b

), and (

c, b, a

) as being identical. The actual number of permutations is a number longer than the rest of this book. But still, if only we knew the extent of any lost cento and had sufficient Latin scholars to weed out the versions where the verbs do not agree, or the rhythm syncopates, or that are just meaningless, and had enough paperâa lost work could be found!

As for Proba, we do not know if her poetic deck-shuffling had the desired effect of converting her husband. Scholars have speculated that it was written around 362, when the Emperor Julian, called the Apostate, had declared that classical texts were not sacrilegious: however, he also forbade Christians to teach and resurrected the old religions, so it would be daring, to say the least, for a writer to negotiate the political, cultural, and theological paradoxes of bending paganism to the ends of Christianity.

Proba's tragedy stems from her use of this singular form. Unlike the majority of female Roman authors, Proba is still represented by one work, although we have none of her own words. Without knowing the date of composition, it is impossible to decide if the

Cento

is a wry parlor game or a sly act of subterfuge. She shimmers, trapped on the cusp of becoming lost.