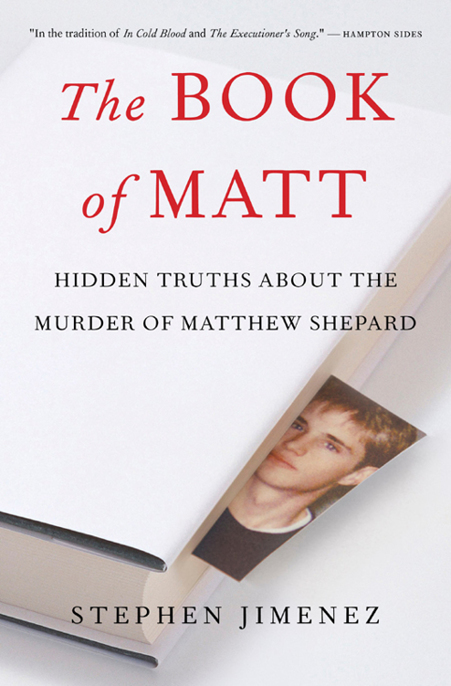

The Book of Matt

Authors: Stephen Jimenez

Copyright © 2013 Stephen Jimenez

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to:

Steerforth Press L.L.C., 45 Lyme Road, Suite 208,

Hanover, New Hampshire 03755

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

eISBN: 978-1-58642-215-8

v3.1

This book is dedicated to my mother,

ROSE LEE JIMENEZ,

who paved the way with love and generosity

and to the memory of my grandmother,

JUSTINE GOMEZ,

who taught me to believe

.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

PART ONE:

Darkness on the Edge of Town

Twenty-six: The Fireside Lounge

Twenty-seven: Sounds of Silence

Thirty-one: The Little Bastard

Thirty-four: The Angel of Death

Epilogue

List of Sources

Acknowledgments

AUTHOR

’

S NOTE

All the material in this book is based on research and investigation that I began more than thirteen years ago in Laramie, Wyoming. My search for sources that could help illuminate the truth behind Matthew Shepard’s 1998 murder eventually took me to twenty states and Washington, DC. Portions of this material first appeared in an abbreviated form in a one-hour report I produced for ABC News

20/20

with my colleague Glenn Silber (“The Matthew Shepard Story: Secrets of a Murder,” 2004). Following that broadcast, I continued the investigation on my own.

Nearly fifteen years after Matthew’s gruesome beating on a lonely, windswept prairie, the story of his murder is not over, despite the fact that two perpetrators — Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson — were apprehended, convicted, and sent away for life. Tangled secrets of this landmark crime persist. Like hungry ghosts, they gnaw quietly and invisibly at facets of our collective soul that cling to a mythic innocence; to a morally simple world of blacks and whites that is, at best, ephemeral. Together we have enshrined Matthew’s tragedy as passion play and folktale, but hardly ever for the truth of what it was, or who he was — much to our own diminishment. As journalist Ellen Goodman observed about the false mythologizing of Private Jessica Lynch’s heroic exploits in the Iraq War, “There is something terrible about the alchemy that tries to turn a human into a symbol … To turn a human into a symbol, you have to take away the humanity.”

While writing this book, I have utilized voluminous public records and media accounts of the Shepard case, including the complete ABC News archive compiled during our investigation. I have also relied extensively on my own interviews with more than a hundred individuals who have firsthand knowledge of the case and/or its principals. These include McKinney and Henderson, the prosecutor, defense attorneys, law enforcement officers from several departments and agencies, judges and other officials, and an array of friends, family members, co-workers, and other associates of both Matthew and his assailants. The prosecutor alone was interviewed for more than 150 hours.

In some instances I have had privileged access to documents and information that were unavailable to journalists who reported on the 1998 crime and the trials that followed, as well as new sources that have emerged in the years since. I have also examined the records of several other state and federal criminal cases whose relevance will become clear in the story that follows.

Pseudonyms are sometimes used when a source would only agree to talk with me on condition of anonymity, either for the protection of privacy or out of legitimate fear of retaliation. In those instances an asterisk follows the pseudonym

*

the first time it appears in the text. All material not based on my personal observation has been carefully reconstructed from the statements, reminiscences, testimonies, communications, and/or notes of sources. A complete list of those sources is included in the appendix.

Though this is a work of nonfiction journalism, I have occasionally employed methods that are slightly less stringent to re-create the dialogue of characters — words I did not personally hear; nor could the characters themselves recall every word exactly from memory. But my intention throughout has been to remain faithful to the actual characters and events as they really happened.

At the end of the aforementioned ABC News report,

20/20

co-anchor Elizabeth Vargas acknowledged, “There is still a lot about the Matthew Shepard murder that we don’t know.” Even then, in 2004, there was a good deal more that we, the investigative team,

did know

but were not yet prepared — or permitted — to report. My additional investigation in the ensuing years picked up where that story left off, but the responsibility for all new material and any inadvertent mistakes or omissions is strictly my own.

— PART ONE —

Darkness on the Edge of Town

ONE

Father and Son

In February 2000 I went to Laramie, Wyoming, to begin work on a story whose essence I thought I knew before boarding the plane in New York. What I expected to find in the infamous college town was an abundance of detail to flesh out a narrative I had already accepted as fact. I went to research a screenplay about the October 1998 murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard — a crime widely perceived as the worst anti-gay attack in US history.

At the time I was teaching screenwriting at New York University and producing documentary films. Like millions of others who followed the news of Matthew’s beating and the subsequent trials of his assailants, I was appalled by the grotesque violence inflicted on this young man. According to some media reports, Matthew was burned with cigarettes and tortured while he begged for his life. As journalist Andrew Sullivan later recalled, “A lot of gay people, when they first heard of that horrifying event, felt punched in the stomach. It kind of encapsulated all our fears of being victimized … at the hands of people who hate us.”

By the time I arrived in Laramie I was a Johnny-come-lately. For more than a year the story of Matthew Shepard’s savage beating and “crucifixion” on a remote prairie fence had been told again and again in the national media. The murder trials had ended by early November 1999 and Matthew’s killers, Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, both twenty-two, had been sentenced to two consecutive life terms with no chance of parole. As far as the media was concerned, the story was finally over.

From the very first reports of the October 6, 1998, attack, major news organizations provided a generally uniform account of the crime and the motives behind it. A sampling of newspaper and magazine stories painted a harrowing picture:

Shepard, 22, a first-year student at the University of Wyoming, paid dearly … allegedly for trusting two strangers enough at the Fireside Lounge to tell them he is gay. What followed was an atrocity that … forced the stunned community [of Laramie] to painfully confront the festering evil of anti-gay hatred, as the nation and its lawmakers watched.

— The Boston Globe

[Police] investigators turned up the following sequence of alleged events … Sometime Tuesday night, Shepard met Henderson and McKinney while at the Fireside Bar and Lounge. Shepard told them he was gay. They invited him to leave with them. All three got into McKinney’s father’s pickup, and the attack began.

— The Denver Post

Hungry for cash, perhaps riled by Shepard’s trusting admission that he was gay, they drove to the edge of town, police say, pistol-whipped him until his skull collapsed, and then left him tied like a fallen scarecrow — or a savior — to the bottom of a cross-hatched fence.

— Newsweek

Albany County Sheriff Gary Puls, who suggested … that the beating was being investigated as a hate crime, said … the investigation … is “aggressively continuing” … Laramie Police Commander Dave O’Malley told the Associated Press that while robbery was the main motive, Shepard was targeted because he was gay …

— The Washington Post

What people mean when they say Matthew Shepard’s murder was a lynching is that he was killed to make a point … So he was stretched along a Wyoming fence not just as a dying young man but as a signpost. “When push

comes to shove,” it says, “this is what we have in mind for gays.”

— Time

magazine

While some gay leaders saw crucifixion imagery in Mr. Shepard’s death, others saw a different symbolism: the Old West practice of nailing a dead coyote to a ranch fence as a warning to future intruders.

— The New York Times

The chilling ordinariness of McKinney’s and Henderson’s small-town backgrounds reminded me of Perry Smith and Richard Hickock, the murderers in Truman Capote’s

In Cold Blood

. In glaring contrast, Matthew Shepard was characterized as “well educated” and “well traveled.” He was “a slight, unassuming young homosexual,”

Newsweek

said, “shy and gentle in a place where it wasn’t common for a young man to be either … [he was] sweet-tempered and boyishly idealistic.”

I was curious about who Matthew was as a person, just as I was bewildered by the warped motives of his killers. But what compelled me as a writer and a gay man to go to Wyoming was neither the brutality of the murder nor its suddenly iconic place in the national landscape. I first began to feel a visceral pull to Matthew’s story when I read the words of his father in a

New York Times

report on Aaron McKinney’s sentencing.

In a hushed Laramie courtroom on November 4, 1999, Dennis Shepard delivered a wrenching soliloquy that brought the tragedy home with fresh impact. His words made it clear that his life had been shattered; that nothing could undo the magnitude of his family’s loss. With TV satellite trucks and throngs of journalists lining the streets outside the county courthouse, and a SWAT team with high-powered rifles standing guard on nearby rooftops, Matthew’s father searched his soul for clues:

How do I talk about the loss I feel every time I think about Matt? How do I describe the empty pit in my heart and mind …

Why wasn’t I there when he needed me most? Why didn’t I spend more time with him? … What could I have done to be a better father and friend? How do I get an answer to those questions now?