Read The Borrowers Aloft Online

Authors: Mary Norton

The Borrowers Aloft (14 page)

She sat still, frowning into space. Her face seemed graven by the memory. "Some said the old men were mad," she went on, after a moment. "But it was wonderfully organized: we were to go in twos—two to each room. The elder ones and the young girls for the ground floor, the younger men and some quite young boys for the creepers."

"What creepers?"

"The creepers up the house front—the vines—of course: they had to search the bedrooms!"

"Yes, I see," said Arrietty.

"That was the only way you could get above the ground floor in those days. It was long before your father invented his hatpin with a bit of tape tied on. There was no way to tackle the stairs—the height of the treads, you see, and nothing to grip on..."

"Yes. Go on about the creepers."

"Early dawn it was, barely light, when the young lads were lined up on the gravel, marking from below which of the windows was open. One, two, three,

GO

—and they was off—all the ivy and wisteria leaves shaking like a palsy! Oh, the stories they had to tell about what they found in those bedrooms, but never a sign of Stainless! One poor little lad slipped on a windowsill and gripped on a cord to save himself. It was the cord of a roller blind, and the roller blind went clattering up to the ceiling and there he was—hanging on a thing like a wooden acorn. He got down in the end—swung himself back and forth until he got a grip on the valance, then down the curtain by the bobbles. Not much fun, though, with two great human beings in nightcaps, snoring away on the bed.

"We girls and the women took the downstairs rooms, each with a man who knew the ropes, like. We had orders to be back by teatime, because of the little 'uns, but the men were to search on until dusk. I had my Uncle Bolty, and they'd given us the morning room. And it was on that spring day, just after it became light"—Homily paused significantly—"that I first saw the Overmantels!"

"Oh," exclaimed Arrietty, "I remember—those proud kind of borrowers who lived above the chimneypiece?"

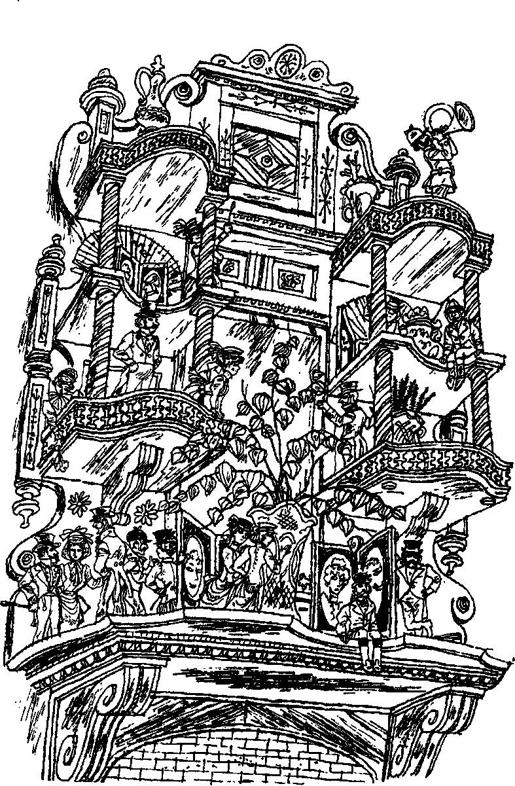

"Yes," said Homily, "them." She thought for a moment. "You never could tell how many of them there were because you always saw them doubled in the looking glass. The overmantel went right up to the ceiling, filled with shelves and twisty pillars and plush-framed photographs. You saw them always gliding about behind the cape gooseberries or the jars of pipe cleaners or the Japanese fans. They smelled of cigars and brandy and—something else. But perhaps that was the smell of the room. Russian leather—yes, that was it..."

"Go on," said Arrietty. "Did they speak to you?"

"Speak to us! Did the Overmantels speak to us!" Homily gave a short laugh, then shook her head grimly as though dismissing a memory. Her cheeks had become very pink.

"But," said Arrietty, breaking the odd silence, "at least you saw them!"

"Oh, we saw them right enough. And heard them. There were plenty of them about that morning. It was early, you see, and they knew the human beings were asleep. There they all were, gliding about, talking and laughing among themselves—and dressed up to kill for a mouse hunt. And they saw us all right, as we stood beside the door, but would they look at us? No, not they. Not straight, that is: their eyes slid about all the time as they

laughed and talked among themselves. They looked past us and over us and under us, but never quite at us. Long, long eyes they had, and funny, light tinkling voices. You couldn't make out what they said.

"After a while, my Uncle Bolty stepped forward: he cleared his throat and put on his very best voice (he could do this, you see—that's why they chose him for the morning room). 'Excuse and pardon me,' he said (it was lovely the way he said it), 'for troubling and disturbing you, but have you by any chance seen—' and he went on to describe Poor Stainless, lovely complexion and all.

"Not a sign of notice did he get. Those Overmantels just went on laughing and talking and putting on airs like as if they were acting on a stage. And beautiful they looked, too (you couldn't deny it), some of the women in their long-necked Overmantel way. The early morning sunlight shining on all that looking glass lit them all up, like, to a kind of pinky gold. Lovely it was. You couldn't help but notice...

"My Uncle Bolty began to look angry, and his face grew very red. 'High or low, we're borrowers all,' he said in a loud voice, 'and this little lad'—he almost shouted it—'was the apple of his mother's eye!' But the Overmantels went on talking in a silly, flustered way, laughing a little still and sliding their long eyes sideways.

"My Uncle Bolty suddenly lost his temper, 'Ail right,' he thundered, forgetting his special voice and going back to his country one, 'you silly, feckless lot. High you may be, but remember this—them as dwells below the kitchen floor has solid earth to build on, and we'll outlast you yet!'

"With that he turns away, and I go after him crying a little—I wouldn't know for why. Knee-high we were in the pile of the morning room carpet. As we passed through the doorway, a silence fell behind us. We waited in the hall and listened for a while. It was a long, long silence."

Arrietty did not speak. She sat there lost in thought and gazing at her mother. After a moment, Homily sighed and said, "Somehow, I don't seem to forget that morning, though nothing much happened really—when you come to think of it. Some of the others had terrible adventures, especially them who was sent to search the bedrooms. But your Great-Uncle Bolty was right. When they closed up most of the house, after her ladyship's hunting accident, the morning room wasn't used anymore. Starved out, they must have been, those Overmantels. Or frozen out." She sighed again and shook her head. "You can't help but feel sorry for them...

"We all stayed up that night, even us young ones, waiting and hoping for news. The search parties kept arriving back in ones and twos. There was hot soup for all, and some were given brandy. Some of the mothers looked quite gray with worry, but they kept up a good front, caring for all and sundry as they came tumbling in down the chute. By morning, all the searchers were home. The last to arrive were three young lads who had gotten trapped in the bedrooms when the housemaids came up at dusk to close the windows and draw the curtains. It had come on to rain, you see. They had to crouch inside the fender for over an hour while two great human beings changed for

dinner. It was a lady and gentleman, and as they dressed, they quarreled—and it was all to do with someone called 'Algy.' Algy this and Algy that ... on and on. Scorched and perspiring as those poor boys were, they peered out through the brass curlicues of the fender and took careful note of everything. At one point, the lady took off most of her hair and hung it on a chair back. The boys were astonished. At another point, the gentleman—taking off his socks—flung them across the room, and one landed in the fireplace. The boys were terrified and pulled it out of sight; it was a woolen sock and might begin to singe; they couldn't risk the smell."

"How did they get away?"

"Oh, that was easy enough once the room was empty and the guests were safely at dinner. They unraveled the sock, which had a hole in the toe, and let themselves down through the banisters on the landing. The first two got down all right. But the last, the littlest one, was hanging in air when the butler came up with a soufflé. All was well, though—the butler didn't look up, and the little one didn't let go.

"Well, that was that. The search was called off, and for us younger ones at least, life seemed to return to normal. Then one afternoon—it must have been a week later because it was a Saturday, I remember, and that was the day our mother always took a walk down the drainpipe to have tea with the Rain Barrels, and on this particular

Saturday she took our little brother with her. Yes, that was it. Anyway, we two girls, my sister and I, found ourselves alone in the house. Our mother always left us jobs to do, and that afternoon it was to cut up a length of black shoelace to make armbands in memory of Stainless. Everybody was making them—it was an order 'to show respect'—and we were all to put them on together in three days' time. After a while, we forgot to be sad and chattered and laughed as we sewed. It was so peaceful, you see, sitting there together and with no fear anymore of black beetles.

"Suddenly my sister looked up, as though she had heard a noise. 'What's that?' she said, and she looked kind of frightened.

"We both of us looked round the room. Then I heard her let out a cry: she was staring at a knothole in the ceiling. Then I saw it, too—something moving in the knothole. It seemed to be black, but it wasn't a beetle. We could neither of us speak or move: we just sat there riveted—watching this thing come winding down toward us out of the ceiling. It was a shiny snaky sort of thing, and it had a twist or curl in it, which, as it got lower, swung round in a blind kind of way and drove us shrieking into a corner. We clung together, crying and staring, until suddenly my sister said, 'Hush!' We waited, listening. 'Someone spoke,' she whispered, staring toward the ceiling. Then we heard it—a hoarse voice, rather breathy and horribly familiar. 'I can see you!' it said.