The Borrowers (2 page)

Authors: Mary Norton

"Under this passage, in the hall below, there was a clock, and through the night he would hear it strike the hours. It was a grandfather clock and very old. Mr. Frith of Leighton Buzzard came each month to wind it, as his father had come before him and his great-uncle before that. For eighty years, they said (and to Mr. Frith's certain knowledge), it had not stopped and, as far as anyone could tell, for as many years before that. The great thing was—that it must never be moved. It stood against the wainscot, and the stone flags around it had been washed so often that a little platform, my brother said, rose up inside.

"And, under this clock, below the wainscot, there was a hole...."

I

T WAS

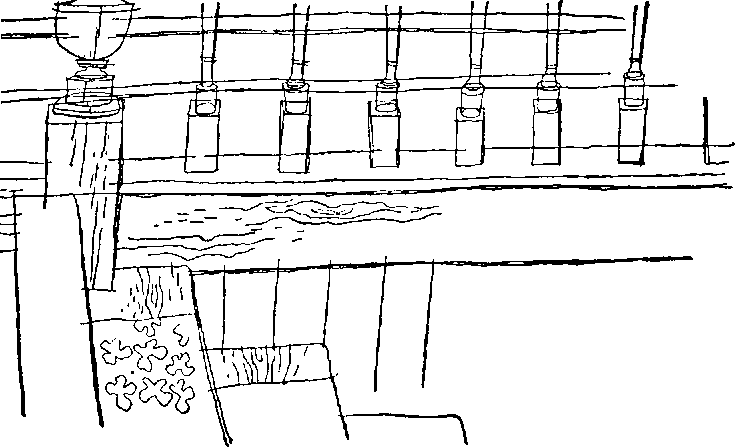

Pod's hole—the keep of his fortress; the entrance to his home. Not that his home was anywhere near the clock: far from it—as you might say. There were yards of dark and dusty passageway, with wooden doors between the joists and metal gates against the mice. Pod used all kinds of things for these gates—a flat leaf of a folding cheese-grater, the hinged lid of a small cash-box, squares of pierced zinc from an old meat-safe, a wire fly-swatter.... "Not that I'm afraid of mice," Homily would say, "but I can't abide the smell." In vain Arrietty had begged for a little mouse of her own, a little blind mouse to bring up by hand—"like Eggletina had had." But Homily would bang with the pan lids and exclaim: "And look what happened to Eggletina!" "What," Arrietty would ask, "what did happen to Eggletina?" But no one would ever say.

It was only Pod who knew the way through the intersecting passages to the hole under the clock. And only Pod could open the gates. There were complicated clasps made of hairpins and safety pins of which Pod alone knew the secret. His wife and child led more sheltered lives in homelike apartments under the kitchen, far removed from the risks and dangers of the dreaded house above. But there was a grating in the brick wall of the house, just below the floor level of the kitchen above, through which Arrietty could see the garden—a piece of graveled path and a bank where crocus bloomed in spring; where blossom drifted from an unseen tree; and where later an azalea bush would flower; and where birds came—and pecked and flirted and sometimes fought. "The hours you waste on them birds," Homily would say, "and when there's a little job to be done you can never find the time. I was brought up in a house," Homily went on, "where there wasn't no grating, and we were all the happier for it. Now go off and get me the potato."

That was the day when Arrietty, rolling the potato before her from the storehouse down the dusty lane under the floor boards, kicked it ill-temperedly so that it rolled rather fast into their kitchen, where Homily was stooping over the stove.

"There you go again," exclaimed Homily, turning angrily; "nearly pushed me into the soup. And when I say 'potato' I don't mean the whole potato. Take the scissor, can't you, and cut off a slice."

"Didn't know how much you wanted," mumbled Arrietty, and Homily, snorting and sniffing, unhooked the blade and handle of half a pair of manicure scissors from a nail on the wall, and began to cut through the peel.

"You've ruined this potato," she grumbled. "You can't roll it back now in all that dust, not once it's been cut open."

"Oh, what does it matter?" said Arrietty. "There are plenty more."

"That's a nice way to talk. Plenty more. Do you realize," Homily went on gravely, laying down the half nail scissor, "that your poor father risks his life every time he borrows a potato?"

"I meant," said Arrietty, "that there are plenty more in the storeroom."

"Well, out of my way now," said Homily, bustling around again, "whatever you meant—and let me get the supper."

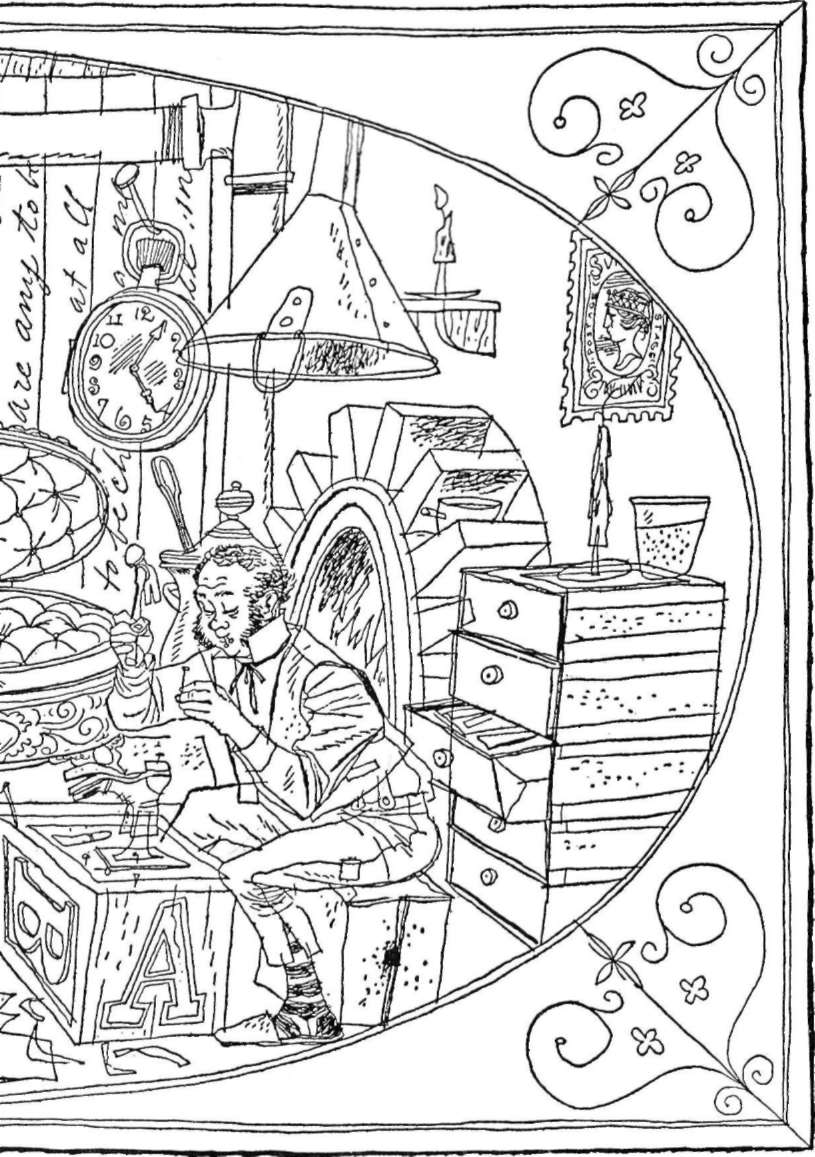

Arrietty wandered through the open door into the sitting room. Ah, the fire had been lighted and the room looked bright and cozy. Homily was proud of her sitting room: the walls had been papered with scraps of old letters out of waste-paper baskets, and Homily had arranged the handwriting sideways in vertical stripes which ran from floor to ceiling. On the walls, repeated in various colors, hung several portraits of Queen Victoria as a girl; these were postage stamps, borrowed by Pod some years ago from the stamp box on the desk in the morning room. There was a lacquer trinket box, padded inside and with the lid open, which they used as a settle; and that useful stand-by—a chest of drawers made of match boxes. There was a round table with a red velvet cloth, which Pod had made from the

wooden bottom of a pill box supported on the carved pedestal of a knight from the chess set. (This had caused a great deal of trouble upstairs when Aunt Sophy's eldest son, on a flying mid-week visit, had invited the vicar for "a game after dinner." Rosa Pickhatchet, who was housemaid at the time, gave in her notice. After she had left other things were found to be missing, and no one was engaged in her place. From that time onwards Mrs. Driver ruled supreme.) The knight itself—its bust, so to speak—stood on a column in the corner, where it looked very fine, and lent that air to the room which only statuary can give.

Beside the fire, in a tilted wooden bookcase, stood Arrietty's library. This was a set of those miniature volumes which the Victorians loved to print, but which to Arrietty seemed the size of very large church Bibles. There was Bryce's

Tom Thumb Gazetteer of the World,

including the last census; Bryce's

Tom Thumb Dictionary,

with short explanations of scientific, philosophical, literary, and technical terms; Bryce's

Tom Thumb Edition of the Comedies of William Shakespeare,

including a foreword on the author; another book, whose pages were all blank, called

Memoranda;

and, last but not least, Arrietty's favorite Bryce's

Tom Thumb Diary and Proverb Book,

with a saying for each day of the year and, as a preface, the life story of a little man called General Tom Thumb, who married a girl called Mercy Lavinia Bump. There was anw engraving of their carriage and pair, with little horses—the size of mice. Arrietty was not a stupid girl. She knew that horses could not be as small as mice, but she did not realize that Tom Thumb, nearly two feet high, would seem a giant to a Borrower.

Arrietty had learned to read from these books, and to write by leaning sideways and copying out the writings on the walls. In spite of this, she did not always keep her diary, although on most days she would take the book out for the sake of the saying which sometimes would comfort her. Today it said: "You may go farther and fare worse," and, underneath: "Order of the Garter, instituted 1348." She carried the book to the fire and sat down with her feet on the hob.

"What are you doing, Arrietty?" called Homily from the kitchen.

"Writing my diary."

"Oh," exclaimed Homily shortly.

"What did you want?" asked Arrietty. She felt quite safe; Homily liked her to write; Homily encouraged any form of culture. Homily herself, poor ignorant creature, could not even say the alphabet. "Nothing. Nothing," said Homily crossly, banging away with the pan lids; "it'll do later."

Arrietty took out her pencil. It was a small white pencil, with a piece of silk cord attached, which had come off a dance program, but, even so, in Arrietty's hand, it looked like a rolling-pin.

"Arrietty!" called Homily again from the kitchen.

"Yes?"

"Put a little something on the fire, will you?"

Arrietty braced her muscles and heaved the book off her knees, and stood it upright on the floor. They kept the fuel, assorted slack and crumbled candle-grease, in a pewter mustard-pot, and shoveled it out with the spoon. Arrietty trickled only a few grains, tilting the mustard spoon, not to spoil the blaze. Then she stood there basking in the warmth. It was a charming fireplace, made by Arrietty's grandfather, with a cogwheel from the stables, part of an old cider-press. The spokes of the cogwheel stood out in starry rays, and the fire itself nestled in the center. Above there was a chimney-piece made from a small brass funnel, inverted. This, at one time, belonged to an oil lamp which matched it, and which stood, in the old days, on the hall table upstairs. An arrangement of pipes, from the spout of the funnel, carried the fumes into the kitchen flues above. The fire was laid with match-sticks and fed with assorted slack and, as it burned up, the iron would become hot, and Homily would simmer soup on the spokes in a silver thimble, and Arrietty would broil nuts. How cozy those winter evenings could be. Arrietty, her great book on her knees, sometimes reading aloud; Pod at his last (he was a shoemaker, and made button-boots out of kid gloves—now, alas, only for his family); and Homily, quiet at last, with her knitting.

Homily knitted their jerseys and stockings on black-headed pins, and, sometimes, on darning needles. A great reel of silk or cotton would stand, table high, beside her chair, and sometimes, if she pulled too sharply, the reel would tip up and roll away out of the open door into the dusty passage beyond, and Arrietty would be sent after it, to re-wind it carefully as she rolled it back.

The floor of the sitting room was carpeted with deep red blotting paper, which was warm and cozy, and soaked up the spills. Homily would renew it at intervals when it became available upstairs, but since Aunt Sophy had taken to her bed Mrs. Driver seldom thought of blotting paper unless, suddenly, there were guests. Homily liked things which saved washing because drying was difficult under the floor; water they had in plenty, hot and cold, thanks to Pod's father who had tapped the pipes from the kitchen boiler. They bathed in a small tureen, which once had held

pâté de foie gras.

When you had wiped out your bath you were supposed to put the lid back, to stop people putting things in it. The soap, too, a great cake of it, hung on a nail in the scullery, and they scraped pieces off. Homily liked coal tar, but Pod and Arrietty preferred sandalwood.

"What are you doing now, Arrietty?" called Homily from the kitchen.

"Still writing my diary."

Once again Arrietty took hold of the book and heaved it back on to her knees. She licked the lead of her great pencil, and stared a moment, deep in thought. She allowed herself (when she did remember to write) one little line on each page because she would never—of this she was sure—have another diary, and if she could get twenty lines on each page the diary would last her twenty years. She had kept it for nearly two years already, and today, 22nd March, she read last year's entry: "Mother cross." She thought a while longer then, at last, she put ditto marks under "mother," and "worried" under "cross."

"What did you say you were doing, Arrietty?" called Homily from the kitchen.

Arrietty closed the book. "Nothing," she said.

"Then chop me up this onion, there's a good girl. Your father's late tonight...."

S

IGHING

, Arrietty put away her diary and went into the kitchen. She took the onion ring from Homily, and slung it lightly round her shoulders, while she foraged for a piece of razor blade. "Really, Arrietty," exclaimed Homily, "not on your clean jersey! Do you want to smell like a bit-bucket? Here, take the scissor—"

Arrietty stepped through the onion ring as though it were a child's hoop, and began to chop it into segments.