The Bottom of the Jar (27 page)

Read The Bottom of the Jar Online

Authors: Abdellatif Laabi

“I guess your horse flew away, huh?”

“May he trample you under his hoofs and make mincemeat out of you!” she retorted.

Faced with that less-than-enviable fate, the solution I found was to shout myself hoarse, joining with the chorus of invocations:

Oh Lord of glory, Moulana ya doul-jalal

. . .

Was it the meager contribution I spilled into the communal emotion that brought on the steel bird? I was so naïve I actually believed that. Announced by a frightening roar, the helicopter sprang out of nowhere, lit up the star-studded sky with red and green flashes, and began spinning above our heads. A short silence followed, after which people let out a flood of hostile rebukes and angry gestures at the helicopter's occupants. Disappointed by the negative reception, the helicopter rose straight up and flew past the moon, “on the double” one would have said, so as to obscure the sultan's face, and then disappeared into the distance. The people clapped, drunk with victory. It didn't last long. The helicopter announced its return. It reappeared and some believed they'd seen flashing lights leave its cockpit, accompanied by sharp explosions. Driss, an expert in this field by virtue of having handled fantasia rifles, cried out: “They're bringing out the big guns!”

Panic ensued. For once playing the role of mother hen, Ghita fussed over her chicks: “This isn't a game anymore children. Go on, scram, kids, go downstairs.”

We resolved not to budge, especially since we really hadn't seen or heard anything this time. The helicopter had gone away once more, giving us a reprieve. People let out a sigh of relief and went back to the object of their fascination. A thin veil covered the moon. Yet this mist didn't impede the conversation that was dissecting each and

every detail. Our neighbor's wife raved about how handsome the king was.

“He is blessed by God,” she said, “an artist's hand has drawn his eyebrows and endowed his eyes with the roundness of a crystal glass.”

“His face shines with the light of Mecca,” Ghita added. “Even the moon must be jealous of it.”

“Have you noticed how straight his nose is, how it's neither turned up nor hooked?”

“Is that a beauty spot on his cheek?”

“Beauty spot or not, he has a rosy complexion. It's as if blood were about to spurt from his cheeks.”

Zhor made a bizarre remark: “Happy is the woman who enjoys her baraka day after day!”

Faced with these tributes praising Ben Youssef's physical charms, I would have expected the men to feel somewhat jealous. There wasn't a bit of that. Leaving the women to their hackneyed attempts at poetry, the men brainstormed with the aim of producing some solid ideas. Our neighbor, who was keen on economics, came up with an analysis that made our mouths water.

“Are you aware that when the French leave, we'll be left with enough phosphates to cover a family's needs for three months without having to work?”

“It's a steamed chicken served with its own cumin,” Driss exulted.

“I'm afraid so, Sidi, and as for the lands that belong to the colonial settlers, we will repossess them and use them to grow enough wheat to feed every single Muslim on Earth.”

“Barley will become something fit only for animal feed.”

“We won't have sent our children to school in vain. It won't be long before they will become administrators and distribute what needs to be distributed.”

“You scratch my back and I'll scratch yours.”

“Why not? We have emptied our

choukaras

so that they could become educated and climb to the top of the ladder. Now it's time for us to put up our feet and relax.”

“We certainly deserve to. We've slaved away our whole lives and worn out our hands and eyes. It is time to rest our heads on a pillow and retire in comfort.”

“

Istiqlal

is a great thing,” our neighbor concluded emphatically.

The celebrations died down only very late when the crowds on the terraces started to thin out. We followed suit. Once we'd gone downstairs, I noted with bitterness that we had skipped dinner. Ghita must have thought that we'd eaten enough with our eyes, and after all, inshallah, thanks to independence, we would soon feast to our heart's content. Less susceptible to these arguments than my head, my stomach started to grumble. But I didn't have a choice. I was therefore forced to avail myself of the only refreshment that was readily available: sleep.

W

HAT DID

I dream of that night? Tales of gluttony, of course. It was a

nzaha

in the Bab Lahdid orchard. As with the previous occasion, the whole family was there, including Touissa, who was an early riser. The order of the day: a great feast. Ghita had secured the services of a caterer. There was the smell of barbecue in the air, as well as roast chicken, tagines, and the inevitable couscous. What was all this in honor of? It was twofold: We were celebrating Driss's return from his pilgrimage to Mecca, and at the same time, we were waiting for a distinguished guest to make his appearance.

The images rolled on, too jumpy for my taste. Driss was seated at the place of honor in the middle of the garden. He was wearing traditional garb and emanating an air of self-importance out of keeping with his character. He was holding his hands out in a dramatic way. Each of us

then presented ourselves in front of him and congratulated him on his journey by loudly pronouncing his new title of haji and then kissing both sides of his hands. Ghita did the same and then seized the opportunity to slip in a humble request: “What about me, haji? When will you send me to see the Prophet's grave?”

“Soon, soon,” Driss replied in a lordly tone. “I won't forget you.”

All this unfolded under the brightness of a . . .

lune de plomb

. The image was fleeting but its materiality left not a shadow of a doubt in the dreamer's mind.

Click click. The master of visions proceeded to the next slide. The whole gathering was seized with hysterical laughter. The reason? Me, sitting on a table with a

watani

on my head, reciting in an affected manner the nursery rhyme I had been taught by my brother Si Mohammed:

Tonio and Cabeza

And their accomplice, the bald one

Surrounded by woods . . .

Click click. A bunch of us were shaking the branches of a tree. Heavy golden fruit fell down. I tried to bite into one, and my teeth encountered nothing but metal.

Click click. Ghita dashed toward the corner where the food was being prepared, shouting, “I smell something burning. What is that cook up to? May fever strike her down!”

Click Click. The

khatib

who had been murdered in front of our house was there, as if he'd been invited, and he addressed us: “I have brought you a sugarloaf and some good Meknes mint.”

Click click and knock knock. Someone knocked at the door of the garden. A commotion stirred outside, and Ben Youssef himself came in, flanked by two rows of dignitaries. His face looked exactly like it

had on the moon. He stepped forward and we rushed over to kiss his hand. He took his seat at the place of honor and leaned over to Driss, asking him with a lisp: “Lithen up and tell me vere have I come from?”

“From Madame Cascar, Sidi, and Moulay.”

Ben Youssef broke into heartfelt laughter, and we joined in. My chuckle rose above all the others.

It was the laughter that woke me up in a start. Alas, the only thing I'd savored at the

zerda

were the enticing smells in the air.

T

HE SUN HAD

risen on our city, which was in the grips of an altogether different dream. Dispatched by Ghita to buy some fritters â she made up for dinner by preparing us a kingly breakfast â I found everyone out on the street. People kept stopping â trying to outdo one another with eloquent greetings â to reminisce and delight in the vision they'd witnessed the previous night. Their faces were beaming, their breasts filled with a newfound pride. There was a crowd in front of the fritter vendor. Ghita hadn't been the only one to have such an idea. I had to elbow my way through a little and stay alert so I wouldn't miss my turn, while trying not to forget the orders I'd been given. I was to ask for a kilo of regular-size fritters, half a kilo of smaller ones, and three kilos of the ones glazed with eggs. It was all getting muddled up in my head when two kids approached the crowd and announced to whoever could hear: “Buy Ben Youssef on the moon!”

I thought they were talking about a newspaper that related the story. Prompted by curiosity, I foolishly gave up my place in the queue so as to get a closer look. Other dupes did the same. We then discovered what all the fuss was about, the object clearly spoke for itself.

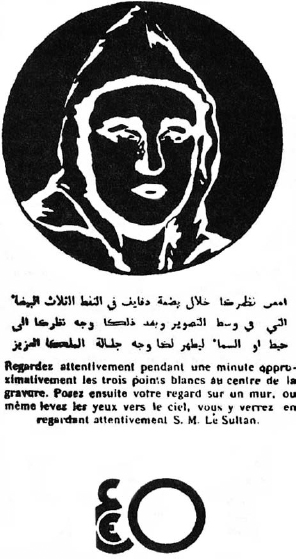

S

PEND APPROXIMATELY A

minute looking closely at the three white dots at the center of the print. Then turn your gaze to a wall or even lift your eyes toward the sky, and if you look hard enough you will see His Majesty the Sultan.

All of the effigies sold out in the blink of an eye. I managed to secure one and immediately set myself to the task. The results were undeniable. Lifting my eyes to the sky, I was certain that the image I'd had so much trouble discerning the previous night exactly matched the descriptions of the face that the others had convinced me had been there all along. Any lingering doubts I might have entertained were definitely brushed aside. The scientific approach I had acquired at school had been useful after all. As far as I was concerned, Ben Youssef's appearance on the moon was now a proven fact.

A

BSORBED BY THESE

scholarly experiments, I found myself pushed to the back of the queue and was obliged to cool my heels, while I was increasingly tortured by the enticing smell and sight of the crispy fritters that the vendor was stacking one after the other on a bunch of palm fronds that had been tied together.

Once back at the house, of the two trophies I was brandishing, the most popular by far â against my expectations â were the fritters. The familial atmosphere had cooled down. The adults thought only of stuffing themselves. Only my little sisters deigned to dart a glance at what I deemed the biggest prize, and out of sheer goodwill they consented to take part in the experiment, whose clear results had turned me into a believer.

The conversation that took place after the meal clarified why the family mood had shifted. I was stunned to learn that the radio, which they had tuned into early in the morning, hadn't breathed a word about the miracle that the whole of Fez had witnessed the previous night. While one could overlook the fact that Rabat and Tangiers hadn't said anything, the fact that the event hadn't been reported by Cairo,

Moscow, the

BBC

, Prague, or Voice of America had shocked us to the very foundations of our being. Had the entire world turned a blind eye to our future and the eloquent manifestations of our faith? Had they turned a deaf ear to the widely attested messages delivered by the sky? The same blackout extended to the official press. The morning papers that Si Mohammed had bought were still spouting the usual bile in regard to our fedayeen and the headlines glorified the deeds of the protectorate: a new road had been built, a dock had been enlarged, a free clinic opened, ten new police stations, a shantytown had been razed, free sacks of flour had been handed out to the needy, caids had been rewarded for their loyal service. Who could top that? We only found an allusion to the events that had so radically turned our lives upside down buried deep in the back pages. There was a humor column with a heading that read “A Race of Lunatics,” where the journalist, who'd only signed the piece with his initials â the coward! â addressed the issue in the following manner:

The ungrateful opponents of France's civilizing mission have attempted to deceive their fellow citizens by propagating the preposterous idea that the old sultan, who was legitimately deposed â thanks to widespread support across the country and the efforts of its elite allied to our cause â made an appearance, hold on to your seats, on the moon! It seems this tactic of psychological manipulation, which these agitators learned from their puppet masters in Moscow, had an impact on some uncultivated, simpleminded souls. Instead of helping these people gain insight into the virtues of reason, which we brought into this country, the agents of this pointless and narrow-minded nationalism want to make even bigger fools out of them by pushing them into the arms of a collective hallucination, thereby transforming them

into a race of lunatics. What a dirty trick! In light of this, it's difficult not to be swayed by the argument put forward by one of our illustrious administrators (White Urbanite, no need to give him a name) who had once said in his time: “We'll get nothing out of these Arabs so long as they write from right to left and piss sitting down.”

Dirty dog, curses upon his mother's religion!

His barking didn't stop our caravan from filing up the stairs that night. There was Ben Youssef again, making his appearance on the lightly dented moon. The top of his hood was leaning slightly to one side. During the course of the following nights, layers of darkness started to cover his face, first his right eye, then his nose, his mouth, his other eye, and so on. Oblivious to the barking guard dogs and the indifference of the world, we clung to our hope until the final stages of the moon's “revolution.”