The Bower Bird

ANN KELLEY is a photographer and prize-winning poet who once nearly played cricket for Cornwall. She has previously published a collection of poetry and photographs, a book of photos of St Ives families and an audio book of cat stories.

She lives with her second husband and cats on the edge of a cliff in Cornwall where they have survived a flood, a landslip, a lightning strike and the roof blowing off. She runs writing courses for medics and has spoken about her work with patients at several medical conferences. She also runs courses for aspiring poets at her home.

The Bower Bird

is the sequel to

The Burying Beetle

was shorlisted for the Brandford Boase Award and was selected for the WHSmith New Talent Initiative.

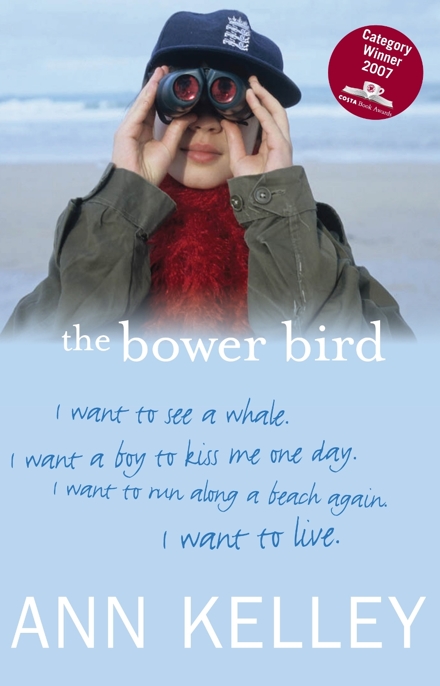

The Bower Bird

won the 2007 Costa Children's Award and the UK literacy Association Book Award.

The Bower Bird

also won the 2008 Cornish Literary Guild's Literary Salver.

Other Books in the Gussie Series

Other Books by Ann Kelley, published by Luath Press

ANN KELLEY

Luath

Press Limited

EDINBURGH

Thanks to Jutta Laing and the RD Laing Trust for permission to reproduce material from

Conversations With Children

; and to Curtis Brown, on behalf of the Estate of AA Milne, for permission to quote from

Winnie Ille Pu

.

First published 2007

This edition 2007

eBook 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-906307-32-5 (children)

ISBN (print): 978-1-906307-45-5 (adult)

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-49-6

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Scottish Arts Council towards the publication of this volume.

© Ann Kelley 2007

Table of Contents

Other Books from Ann Kelley & Luath Press

E

I’m not dead yet.

E

WE’VE BEEN HERE

for two weeks. I’m still not well enough to start at the local school. But the weather has been barmy – or is it balmy? Yes, it probably is balmy. Barmy means daft. The sun has shone on us most days since we moved, and I feel that my heart is going to mend enough to have the operation that could give me a few more years of life.

It’s a cold night and the sky is clear. Stars are appearing one by one. I wear my distance specs to see them otherwise it’s all a beautiful blur. I sit in my window on a stripy cushion and feel… happy.

The lights of the little town are twinkling below me, and there is a nearly full moon – its blue-white wedding veil draped across the bay. The lighthouse winks its bright eye every ten seconds.

I did have a bedside lamp on but moths kept coming in the window to commit suicide. Why do insects that choose to fly around in total darkness have a fatal attraction for hot light bulbs? They must be barmy. Or maybe a hot bulb gives off a smell like female moths and the male moths are attracted to it for that reason.

Even in the middle of the night seagulls are flying all around us, calling to each other in the dark. The wind has got up and the gulls are lifting on invisible currents and then swoop fast like shooting stars.

Our young gull is crouched on the ridge of the roof, his head poking out over the top, watching the adults and whining pathetically. There must be some juvenile gulls up there learning how to fly and land cleanly on the rooftops and chimneys, just as if they are alighting on cliff ledges.

I scrunch up under a warm woolly blanket with my feet up, and Charlie keeps trying to get comfortable but there’s no horizontal bit. She prefers me to be flat in bed so she can warm herself on my tummy, or my chest. She shouldn’t really sit on my chest as I have trouble breathing at the best of times and anyway, I had open-heart surgery last year, when I was eleven, and the healing process hasn’t finished yet. The operation was a waste of time. It was supposed to be one of three procedures to repair the various heart defects. When I was opened up they could see that I had no pulmonary artery, not even an excuse for one, and there was nothing to build on. So the surgeon just closed me up again. I now have an amazing scar that cuts me in half almost, as if I have survived a shark attack.

Poor Charlie, she doesn’t understand why I don’t want her on my chest.

I reluctantly leave the starlit night and get into my bed. I’m reading a really good book by Mary Webb called

Gone to Earth

. It’s about a girl who has a pet fox. Mary Webb has written several other books. I’ll have to look out for them at car boot sales or in the second-hand bookshop, as they are so old they are probably out of print.

As usual, the three cats wake me. Charlie is the noisiest and the most demanding. As soon as there’s a glimmer of daylight she starts on at me to get up and feed her. She meows loudly and jumps on the bed and marches up and down on one spot, as if I am her mother and she is trying to make the milk come. She sound quite cross. If I pretend to sleep she gets really irate. The other two are more patient but they stare, accusingly. I can feel their eyes on me. Flo sits on the chest of drawers and Rambo on the window seat.

I wake to a completely pink dawn. Outside everything is saturated with an intense rosy glow. Pink sky, sea and bay. Pink roofs, candy sand. I yearned for a party dress when I was five or six, of exactly this shade – to match my Barbie doll’s outfit.

By the time I find my specs, put on a dressing gown and flip-flops, load a film into my camera and lean out the window, the pink has paled and silvered, but the sun now hangs heavily above the dunes, like a red balloon full of liquid. One small boat chugs out of the harbour dragging a pink wake and gulls are following in a raucous rush.

I am surrounded by hungry cats. I better give in. Charlie is jubilant, running ahead down the stairs, calling me to hurry up. The others follow behind me.

I have to go to the bathroom first, and this really makes Charlie cross. She never knows whether to come in with me at this point, because she usually spends bath-time with me, but now she can only think about her rumbling stomach.

Mum is in the bathroom for longer and longer every morning. What does she do in there? She told me once that she hadn’t had a decent crap since I was born. First I screamed all the time, then as I got bigger I banged on the door and yelled. When I was a baby I screamed for twenty-one hours once – she wasn’t in the bathroom all that time, of course. She says I’m lucky to be alive as she nearly strangled me several times. Sleep deprivation makes you go barmy apparently.

‘Mum, I have to wee, I’m desperate.’

She’s looking into a magnifying mirror and doing some- thing disgusting with scissors up her nose.

‘Ohmygod, Mum, that’s gross. You’ll slice through your mucus membranes.’

‘They’re blunt-ended, Gussie. You wait until you get hairy nostrils. See how you like it.’

Hopefully I won’t live that long.

She does all this other stuff, too, to her face, plucking and scraping and applying various very expensive unguents. What a lovely word – unguents.

‘Is it worth it, Mum?’

‘Probably not, but I’m not giving up just yet.’

She’s actually quite cool looking, I think, but because she had me when she was forty-one she is quite old now. It doesn’t bother me much, but it bothers her. She’s shaving her armpits now. What a palaver. I don’t have any pubic hair yet, as I am small for my age – my heart wants me to be small, so it doesn’t have to work too hard.

‘Mum, can I help unpack something today?’

‘Yeah, why not? We’ll have a look in some of the smaller boxes from Grandma’s.’

Grandma was small and plump and she knitted and sewed, tatted, smocked and embroidered. You never saw her without something in her hands that she was working on. Their garden was a fruit bowl of gooseberries and blackcurrants, redcurrants and raspberries, loganberries and strawberries. I used to throw a tennis ball up onto the roof of their bungalow and catch it when it bounced off the gutter. Another game with the ball was to roll it along the wavy low brick wall, which went around the front garden, and see how far it would go before it fell off. I got quite good at that.

They lived in Shoeburyness, quite close to London, where we lived when we were still a family, before Daddy left.

Like me, he’s an only child. His parents, who I never met, came from this town.

Mum doesn’t have any brothers or sisters either, so I have no aunts, uncles or cousins on her side of the family. There’s only Mum now. Except that we are called Stevens and there are at least a hundred Stevenses in St Ives. I am determined to find my lost Cornish family, somehow.