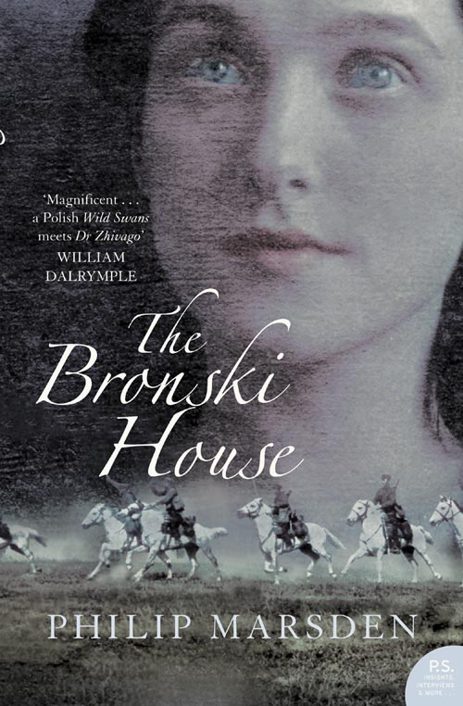

The Bronski House

Authors: Philip Marsden

The Bronski House

London, New York, Toronto and Sydney

For Nick and Pandora Wesolowski

1

T

HERE WAS A HOUSE

I knew as a child, grey-fronted, steep-lawned, with a bird’s-eye view of a Cornish harbour. The house was set apart from the village, in its own ring of elm trees. From the lawn, you looked down the slope and over the treetops to a granite quay. The quay curled around the fishing tenders which bobbed about inside it. Beyond them, the bay widened towards a pair of headlands fringed with pine trees, a kind of gateway to the plains of the open sea.

In front of the house was a monkey-puzzle. It was tall and very straight with no branches until right at the top where a Medusa’s-head of bracts burst out from the trunk. The tree had been planted by a sea-captain, one hundred and fifty years earlier. His last mission had been to take a member of the Portuguese royal family into exile in South America. For this he had been rewarded with a casket of gold and a bag of araucaria seeds. The gold he used to build the house. The seeds he planted in front of it. He called the house: Braganza.

For a few weeks every year we went to a cottage in the village below Braganza. It was August. The bay was hazy. White sails drifted across it. The chorus of the gulls was relentless. The lawn at Braganza, where we went to tea on Sundays, was as dry as a desert.

For years, Cornwall was the only abroad I knew. Crossing the Tamar, on an old stone bridge the colour of elephant skin, I closed my eyes and imagined it took two days; when I opened them again I felt sure we would be on some strange and far-off island. But it never worked. If Cornwall wasn’t quite England, it wasn’t quite abroad either.

I already knew what abroad would be like; it would be like Braganza. There everything was different – the noises, the food, the smells. The voices you heard from the landing, from behind half-open doors, were foreign ones. Extraordinary things hung on the walls – wolfskins, bearskins, cutlasses, velvet-stocked muskets and icons. There were hand-tinted cartoons on the stairs, eerie wood-cuts of cobblers cobbling and reapers reaping, and perched on high marble plinths, looking somewhat like cockerels, was a vast array of silver samovars.

Braganza was a big house and there were parts of it I never saw. But I knew that some profound sadness lived in its more remote corners. Not an English sadness – a hushed thing, a ‘don’t-go-too-close-dear’ sadness; this was a sadness without shame, something noble, a sadness that could face its own depths, a sadness rooted in truth – a sadness that was also the springboard for joy.

I did not know its name. But I sensed it had something to do with the framed photographs on a cabinet in the drawing room: the stern-gazed women, the tousle-haired sons with their rakish moustaches, the family groups picnicking in the forest. It probably had something to do with the painting of a long, low-fronted house and the larch tree which stood in front of it. But most of all it had to do with the woman who lived there.

Zofia was Polish. She had kind, hooded eyes and a spongy accent which she never lost. She delivered her speech in such honeyed tones that sometimes listening to it, I would forget what she was saying and simply sit there watching her, letting the words fall over me like a balm. I loved her stories and her faraway looks, her pale translucent eyes. I loved the aura that surrounded her. I loved her sadness.

The year I was born Zofia had her fortieth birthday. Her husband owned the two harbourside hotels below the house. He staffed them with waiters from southern Italy who started fights and gave babies to the local girls. When I was five, Zofia bent down to me and whispered, ‘Philip, will you be my friend, my special friend?’

‘Yes, please!’

‘I have four boyfriends already,’ she confessed. ‘My husband, my son and my two dogs. But you, Pheelip, you must be one too. Would you like that?’

After that not a Christmas went by without some surprise gift arriving in the post – an onyx egg, an old postcard of a place called Wilno, a Polish bank note, a pen. The pen was a magic one, she said – it will write magic things for you. She herself wrote magic things: witty, lyrical poems about amorous unicorns, talking lobsters and the strange gentlemen who stayed in her hotels.

Each August she took my brother and me to lunch in one of the hotels. We had to wear ties, and tweed jackets which were too big one year and too small the next. Zofia called the Italian waiters by name (usually the wrong one) and ordered complicated things like prawns and oysters which we slipped into our pockets when she wasn’t looking. But afterwards she would concede to our tastes and ask for rice pudding, which she pronounced ‘Rasputin’.

Then we went onto the terrace and she told stories – fabulous stories, Polish stories. The tide lapped at the wall below us; boats criss-crossed the bay. But Zofia would lean forward, her voice softened to a whisper, and conjure up a much more compelling picture of a darkened forest thick with snow, of howling wolves and a howling wind, of a man all alone in the corner of a clapboard cabin, listening, listening: ‘Vooosh-vooosh! goes the wind… Awooo, awooo! go the wolves…”

Zofia made very convincing noises, and we were there in that clapboard cabin, there with that lonely man, with the whooshing wind, the awooing wolves – listening, listening, listening…

She would then thump the table and cry out and we would all laugh – the two of us with shock, Zofia with mischief, while the starchy English guests at the next tables would raise their eyebrows at the unseemly way this woman – this foreign woman, the hotel’s proprietress – behaved in public with her two little boys.

Zofia had a small boat called

Memory

with a 17 on the mainsail. Seventeen was the age she was when she escaped, and seventeen was the date: 17 September 1939.

She was the worst sailor I have ever known. Utterly unable to grasp the principle of the points of sail – the tacking, the going-about, the gybing – she reverted instead to techniques that she

did

understand: those for riding a horse. She treated the sheets like reins, the halyards like a throat-lash. Her dogs swam alongside and helped to convince her that sailing – feeling the breeze in her hair, contemplating the big questions – was really no different from a ride in the Polish forest.

The language of sailing baffled her too. Each time she rowed out to

Memory

, she first asked Jimmy Green in the boatyard for his advice: ‘Oh, Jeemy, what is the tide doing?’

‘Comin’ in, Mrs Mo,’ he’d say, or, ‘Goin’ out now.’

But by the time she’d reached

Memory

, she couldn’t remember whether it was ‘coming in’ or ‘coming out’, or ‘going in’ or ‘going out’. Nor was she quite sure why it mattered.

On occasions, after some near calamity, she would turn to old Charlie Ferris (‘Whiskers’ on account of his enormous white beard) and ask him, again, to try and teach her to sail. Whiskers would come aboard and point out the sheets and cleats, for’ard and aft, port and starboard, would show her how to find the wind and set the sails, and she’d pretend to understand. But one day she lost the main halyard up the mast and Whiskers, shinnying up to get it, forfeited a large chunk of his beard to a block. After that he wouldn’t go near

Memory

again.

I was ten and a half when, one August evening, Zofia telephoned our cottage and asked for me.

‘Philip,’ she said, in a deep voice reserved for adventures, ‘I am taking

Memory

up the creek to see the swans. Will you come?’

The oak trees came right down to the water. Seaweed hung like witches’ hair from their boughs. Rounding the first bend, we found the ribs of an abandoned ship, but no swans. By the time we rounded the second bend, the evening had cast its spell on the deserted creek and Zofia purred, ‘Oh, isn’t it beautiful!’

And so it was. But the briny scum on the water, the floating twigs and eel grass, had already begun to ebb. Unnoticed they slipped past

Memory’s

hull, while what breeze there was nudged us upstream. Pretty soon there came a soft jolt and

Memory

was lodged firmly in the mud.

‘Oh dear!’ said Zofia.

There was no alternative but to drop the sails and wait for the flood. Zofia didn’t mind a bit.

It became dark. The moon rose. The curlew cried from the mud flats. Zofia’s dogs fell asleep on the bottom-boards. The night filled with little noises.

At first we were silent.

Then Zofia began to sing. She sang in a deep, modulated voice thick with Slavic irony. She sang a Belorussian song about a priest and his dead dog. She tried to teach it to me but I couldn’t make the sounds. She then told a story about two lovers, a ferry on the river Niemen, and a murder; she asked me to decide who was to blame.

‘The man?’

‘Perhaps…’

‘The woman?’

‘Perhaps…’

‘The ferryman?’

She laughed and her laughter echoed in the creek. Leaning back against the folds of the mainsail, she took each of the suspects in turn and explained how, in the real world, the grown-up world, everyone could be culpable – or no one. Looking up at the stars, she then sighed and recited a poem of hers in which the poet envies a scarecrow: ‘I wish there was no thought in me / this head of thought exhausteth me.’

The hours slid past and she settled into a long lilting monologue, punctuated by the cries of the night birds, of the old life in Eastern Poland – the villages and wolf hunts, the larger-than-life people. Scene by scene fell on our marooned boat like the miraculous crystals of dew: funeral carriages in the snow, dead bodies in the river, the sad ghost who sat on her bed complaining, the dragoon who galloped along the river bank, naked but for his leather top-boots.

Then there was the escape itself – Russian tanks approaching through the forest, a hurried flight on farm-carts, the poison her mother carried in a small glass bottle, the final drama at the Lithuanian frontier with bullets screeching around their ears.

But of all the things that she told me that evening, it was the story of the silver that lodged most firmly in my boyish mind. Real treasure, not just the imagined treasure of a vanished world; real treasure, taken into the forest in mushroom baskets before the escape, buried deep in a new plantation, abandoned to hope, while the two most destructive armies the world had ever seen rumbled towards each other through the trees.

‘Is it still there, Zosia?’

‘Maybe.’

‘Why don’t you go and see?’

‘They will not allow me.’

‘But one day they will let you, won’t they, Zosia?’

‘Yes.’

T

HE YEARS PASSED

and we no longer went to Cornwall. I broke free of a protracted education, moved to London, and Zofia and Poland slipped into that burgeoning slush-fund of half-forgotten places and half-forgotten people. I still received word from her – a meditation from Spain on the theme of ‘hot sun and accidie’, telephone calls in which she would demand to know if I was ‘in lerff’, and sprigs of thrift and sea-rocket in the post, lest she and Cornwall should ever slip too far from my thoughts.