The Butcher (2 page)

Authors: Philip Carlo

G

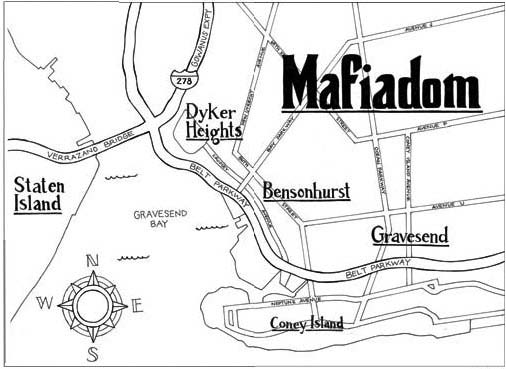

ravesend, Brooklyn, is a seven-thousand-acre swath of land sandwiched between Bensonhurst and Coney Island. The area initially drew its name from a small graveyard located at McDonald Avenue and Neck Road. Beaten and battered and worn down now, the graveyard is still there today. Gravesend was settled by the Dutch in 1640. Between the years 1641 and 1645, before the area was an English settlement, the Dutch had a campaign to rid the area of its indigenous peoples. The Dutch remorselessly murdered them, beheaded them, dismembered them, and gleefully burned them alive at the stake.

Gravesend was strategically close to estuaries fed by the nearby Atlantic Ocean. It was well located for importing and exporting various goods and commodities. The forests of Gravesend were abundant in all manner of game, moose, deer and beaver, wild pig, and huge numbers of rabbits. (Nearby Coney Island is Dutch for “Rabbit Island.”) The waters of the Atlantic were teeming with many varieties of fish. During the summer months, the pristine, unpolluted Atlantic literally boiled with huge schools of anchovy, cod, mackerel, bluefish, bass, fluke, and flounder. Tons of succulent lobster and blue claw crabs were there for the taking. Mountains of oysters, mussels, and clams were easily accessible. The vast, blue skies of seventeenth-century

Brooklyn were filled with edible fowlâquail, duck, and geese. The dark, fertile soil was ideal for bountiful crops. With the exception of the brutal and unforgiving winters, Gravesend was a place of sweet abundance.

As Brooklyn grew to be a large, bustling metropolis, so did Gravesend. In the early twentieth century, the New York Mafia began using the more desolate areas of Gravesend as a convenient dumping ground for bodies. Joe “The Boss” Masseria, Salvatore Maranzano, Lucky Luciano, Murder Incorporated, the five New York crime familiesâGenovese, Profaci, Bonanno, Lucchese, and Anastasiaâall gladly used Gravesend as a convenient place to leave their victimsâstabbed, ice-picked, butchered, beaten, battered, and shot to death.

Up to the day of his arrest, Sammy “The Bull” Gravano had his office smack in the heart of Gravesend, at Highland and Stillwell avenues. The Lucchese, Genovese, Gambino, Colombo, and Bonanno crime families all had secretive black-windowed social clubs in Gravesend and Bensonhurst. Here, mafiosi played cards, drank strong espresso, planned new crimes, murders and hijacks, settled disputes. Thus, Gravesend, Brooklyn, took on a more sinister, morbid connotation to its inhabitants and to the people in nearby Bensonhurst and Coney Island. Here, people minded their own business. Here, no one saw anything. The citizenry could readily be likened to the three wise monkeysâ¦they saw no evil, spoke no evil, heard no evil.

Â

Because Gravesend and its neighbor Bensonhurst had larger populations of “made men” than anywhere else in the world, including Sicily, one of the by-products of their workâbodiesâwas always a concern. Where to hide them; how to get rid of them permanently; whether or not to blatantly leave them out in the open. These were decisions that either had to be made quickly, on the spot, or planned in advance. As vacant lots all across Brooklyn were filled with two- and three-story red-brick homes, the impromptu burial grounds of the area systemati

cally disappeared. The mob, as a collective whole, had to look for new places to hide their victims.

Thus, it was logical that nearby Staten Island came into play. On Staten Island, there were still huge tracts of uninhabited land, blackened swamps, fields covered with tall green grass in the summer that turned a golden, wheatlike hue in the winter. Here, too, were thousands of acres of thick forests of oak, hickory, maple, and beech trees. More important, though, were the state wildlife sanctuaries, which were protected by the government from any kind of development. No construction was allowed; no utility lines would be laid. Surrounded by hundreds of acres of empty land, there was little threat someone idling by would stumble across a body or members of the mob burying one. Inadvertently, the government had invented the perfect place to get rid of bodies for the Mafia, and it didn't take long for particularly cunning members of La Cosa Nostra to take advantage of this convenience.

Always wily, always quick to exploit a situation, the Mafia turned Staten Island's wildlife sanctuaries into its private burial grounds. Interestingly, all five New York crime families used the sanctuaries. One would think members of the mob would keep secret cemeteries private, not tell anyone about them, but just the opposite proved true. They actually shared the sanctuaries with one another. Members of all the five families came to Staten Island with bodies in the trunks of their cars. They drove Cadillacs and Lincolns, Mercedeses and Jaguars, and arrogantly made their way to private burial grounds scattered all over Staten Island, in the south, the north, the east, and the west. They were so sure and confident that they often came across the Verrazano Bridge in broad daylight with bodies and long-handled shovels in the trunks of their cars, as Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Dean Martin, and golden oldies came from their radios. Never speeding, always carefully abiding by traffic rules and regulations, signs and lights, they made their way to these prearranged burial sites, sometimes singing along with Sinatra. Occasionally, there were graves already prepared; most

often, however, shallow graves would be quickly dug in the secret-holding sanctuaries.

One such place was the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge, some eight miles as the crow flies from the great-grand Verrazano Bridge. A caporegime in the Bonanno crime family out of Gravesend, Brooklyn, had made this sanctuary his private burial ground. Here were bodies that had suffered tremendous trauma while the person was still aliveâhere were bodies that had been neatly cut into six pieces: the legs, arms, head, and torso, all separated by skillful cuts that showed no tears. Whoever dismembered these bodies was experienced, methodical, as cold and efficient as a butcher in the meatpacking district of lower Manhattan.

Here there were no tombstones, no reminders of the many who had lost their lives.

Seeds

SANCTUARY

I

t was June 6, 1990. The skies over Staten Island were clear and unblemished, as blue as the eye of a dove. An unusual caravan of police slowly made their way off the Staten Island Expressway and toward the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge. It was a task force composed of crack, hard-faced DEA, FBI, and ATF agents as well as hardcore NYPD organized crime detectives. Prosecutors from the Brooklyn D.A.'s office were also present. Each of these prosecutors, agents, and detectives was tense and uptight. What they were doing today, the reason they were approaching the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge on Staten Island, was the culmination of three and a half years of hard work, blood and sweat and tearsâliterally.

In the second vehicle of this solemn caravan sat DEA agent Jim Hunt, the lead investigator of a DEA task force that had been pursuing a notorious Bonanno capo by the name of Tommy “Karate” Pitera. Hunt was a five-foot-ten, thickly muscled Irishman; he had a pale, handsome countenance and large, all-seeing, Paul Newman-blue eyes. A stoic, exceedingly dedicated third-generation cop, Jim took his work very seriously, was highly motivated, tenacious, though he was quick to laugh and quick to smile with no strings attached. He would gladly help a colleague or friend in need.

Hunt had an unusual sense of fair play for a cop. As much as he hated drug dealers, drug abusers, and bad guys, he empathized and sympathized with some of their plights. Hunt viewed drug abuse more as a medical problem. He well understood that while some people can have a social drink or two, others become alcoholicsâ¦the dregs of society. What Jim Hunt was after, what he had his sights on, were the drug lordsâthose in faraway places, distant lands, who had learned to manipulate the system in such a way that they had become some of the wealthiest people in the world. The drug lords not only usurped the rule of law but gleefully defecated all over it. This foe, this enemy, was not only in distant lands. It was here, also. Homegrown. The Mafia, the bosses and capos of each of the families, was dealing in drugs, Jim knew.

What was particularly unusual about this group of law enforcement agents serpentining through Staten Island that June day was that they were all cooperating with each other. Most often, there is a fierce, bare-knuckled competition between the FBI and the DEA, the NYPD and the ATF; they were competitors in perpetual pissing contests, not colleagues. But this case was so unusual, the stakes so dire, that each of the agencies had made peace and were truly cooperating with one another on a large scaleâa rare thing.

Sitting alongside Hunt was his fellow DEA agent and partner, Tommy Geisel. Geisel and Hunt were so close that they were more like brothers than partners in the war against drugs. For years, they'd been trusting one another with their lives. Geisel was a large, broad-shouldered, strapping individual. He had, in the parlance of the DEA, “brains, balls, and brawn,” a phrase commonly used within the agency to describe the type of men they were looking for. Geisel was the kind of guy that Jim wanted in his foxhole, and there was no one else he wanted watching his back.

Accompanying this variegated army of police was a bad guyâsomeone who wore a black hat, who would ultimately draw the curtains back and reveal the true horrors that even this group of law enforcement would soon be shocked and stunned by. He was tall and

thin; his nose resembled a toucan's beak. This bad guy was nervous and unsettled to the core of his being. Over the last four years, he had become, quite literally, unhingedâpushed to his limits by mind-numbing violence and unspeakable barbaric acts as people around him were tortured, cut up, summarily discarded.

Some thirteen months before, ASAC Hunt had heard that a Bonanno family capo, Tommy Pitera, was leaving bodies on Staten Island. An Israeli drug dealer named Shlomo Mendelsohn had gotten himself in trouble and offered to give up the whereabouts of Pitera's cemetery. The only problem was Shlomo couldn't remember exactly where the cemetery was located. He had only been there once and it was at night. He had never been to Staten Island before the time he went with Pitera to dispose of a body. At one point during their quest to find Pitera's cemetery, Shlomo had even said, scratching his head, “I'm thinking maybe it was New Jersey, not Staten Island.”

Shlomo was deeply immersed in selling huge amounts of cocaine in Manhattan, but Staten Island and New Jersey were completely foreign to him. Though Shlomo had seemed sincere and truthful, he had stepped up to bat and struck out.

Now Jim Hunt was back with another man who said he knew where Pitera's victims were. Hopeful, though wary, Jim's keen blue eyes moved left and right as the caravan slowly crept forward. As they approached a desolate street, the bad guy said, “Hereâ¦here, this is it! I'm almost sure.”

The problem was that, like Shlomo, this bad guy had only been there in the dead of night. Daylight cast the stage of horrors that existed here in warm, welcoming light. That June day was cloudless, and the sun shone with such unharnessed brilliance most all the agents donned sunglasses. Because of the fierce sunshine, it looked more like the south of France or a Mediterranean island than a Mafia burial ground.

The caravan moved right. Like a giant anaconda coming to a sudden stop, all the vehicles became immobile. Serious-faced and

curious, each of the law enforcement professionals stepped from an air-conditioned car. The hot, humid air struck them like a wet towel. As though on cue, an unruly gang of crows noisily cawed in different trees spread throughout the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge.

Concerned about contaminating the area, losing potential evidence, all the agents and NYPD cops began to put on white jumpsuits made of thin, malleable paper. Having a good, easy rapport with the informer, Jim Hunt asked, “Where?” his eyebrows raised skeptically.

“Oh, man,” the informer said, his brow creasing, the weight of the world suddenly on his shoulders. Sweating, licking his lips, smoking a cigarette, the bad guy moved into the thicket of poplar and elm and pine trees spread out before them. He had a worried look about his face. He seemed confusedâlost. He took about thirty cautious steps into the sanctuary, stopped, looked around as some twenty-five pairs of cynical-wary cops' eyes regarded him with a mix of trepidation and curiosity.

He began moving north, stopped, turned around and moved south. He looked down. He scratched his head. He regarded Jim Hunt. He liked Hunt. He wanted to please him. Hunt was a straight shooter and the bad guy knew that whatever Hunt promised him, he would get. It was already agreed that the federal government, because of his cooperation, would put him and his family into the Witness Protection Program. He had no reason to lie. If he had any future, he had to cooperate with the feds. He knew he had to give them what they wanted.

“The problem,” the informer apologized, “is that I was here at night. It's very hard to tell one spot from another. You know, it's like really the same.” He looked down at the ground. It was covered with a carpet of dead leaves and foliage. The thick smell of wet soil and mildew hung in the humid air. There was nothing to indicate that humans had been buried here; no bald spots; no sudden bursts of greeneryâno telltale sign of human death. The crows continued to caw. Their ruckus was distracting. A chain-smoker, the informer lit one cigarette after another. Beads of sweat ran down his

face. Jim called an impromptu brainstorming session among all the law enforcement there that day. They, as a collective body, believed what the informer had said. They knew Pitera was murdering people as though he had a God-given right, as though he had a license to kill, and that the informer had no reason to lie. They decided that until proven otherwise, they'd believe him and move full out until they found Pitera's victims. Hunt and Geisel believed that Pitera had killed over sixty people.

The NYPD set up a command center. Uniformed cops were posted all around the bird sanctuary, roughly twenty-five acres in size. They knew that once the news media got wind of a Mafia burial ground, they'd have reporters sniffing around like hungry hounds within hours. Finding bodies buried months and years ago here, without coordinates, without landmarks, would be no easy task, like looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack, though none of that was going to dissuade any of the hardcore law enforcement professionals there that fateful day. They continued looking without luck. The fierce June sun reluctantly dropped below the line of trees. Long shadows appeared. Silently, dusk descended onto the sanctuary. The sounds of crickets and frogs came from every direction at once. Large flocks of sparrows chattered rapidly. The birds, troubled and nervous by the cops' sudden presence, knew the secrets that their sanctuary held.

Foul flesh, silent screams, and nightmares. As dark continued to envelop the sanctuary, agents and police there decided they would again start up the search the following morning.